For NCMEC’s Forensic Artists, Every Face Tells A Story, Every Child Has A Name

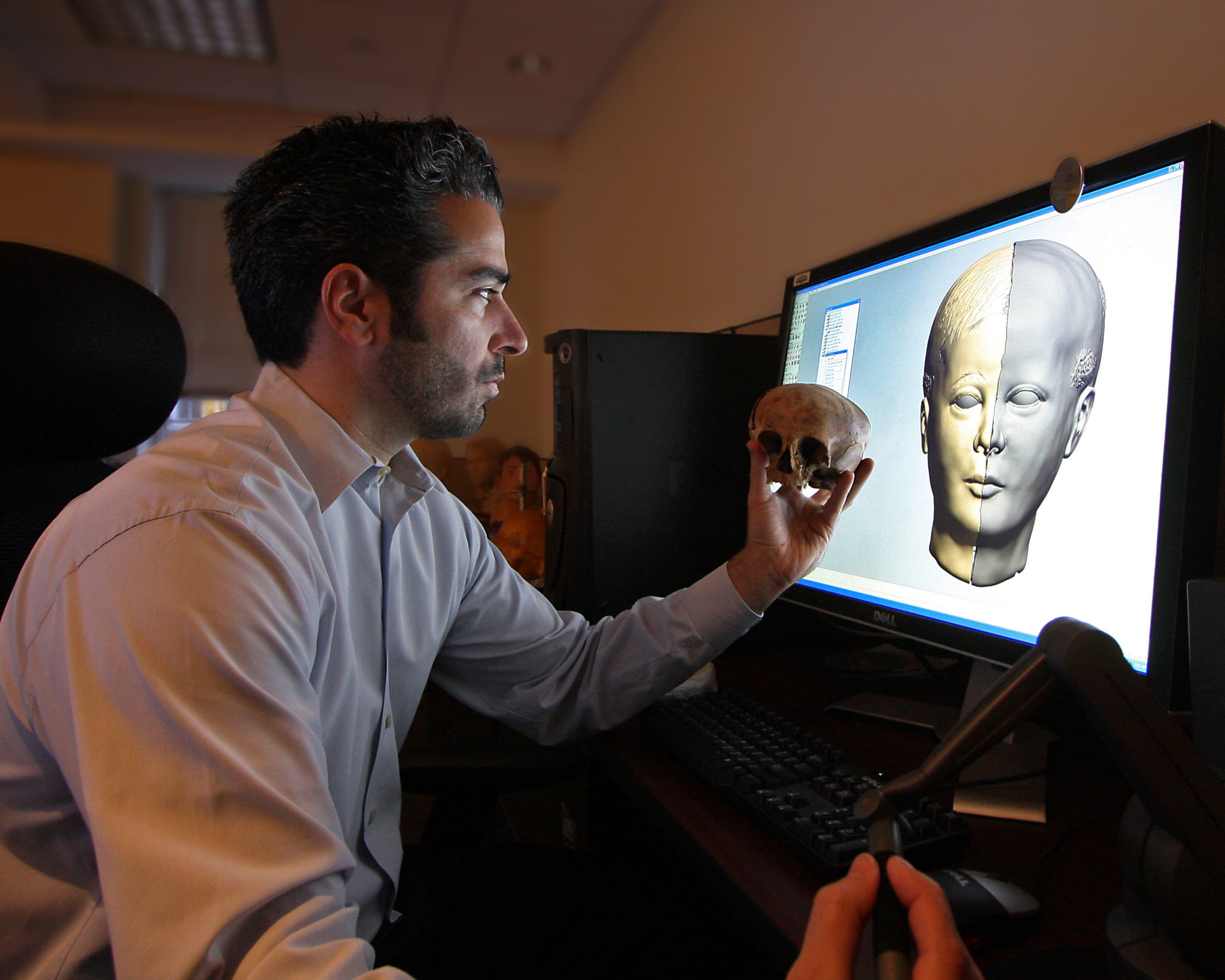

Above: National Center for Missing & Exploited Children forensic artists, Colin McNally and Joe Mullins, at work in Alexandria, Virginia. Mullins is holding 3D prints of skulls. Photo credit: NCMEC Senior Multimedia Editor Sarah Baker, courtesy NCMEC

By Kadambari M. Wade

Nestled in the middle of Alexandria’s bustling historic district, and walking distance from the serene waters of the Potomac, the popularity of this Virginia area might make it an unlikely setting for the command center from which some of America’s most critical battles are planned and fought. But there is nothing typical about the work of NCMEC, the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children, the group that leads the nation’s fight against child abduction, abuse, and exploitation, and is the country’s clearinghouse and reporting center for all issues related to the prevention of and recovery from child victimization.

It is here that forensic artist Colin McNally, the Supervisor of the Forensic Imaging Unit at NCMEC, and his team wage their relentless fight in the name of the thousands of American children that remain missing year after year, mixing technology with age-old patience, years of dedicated artistry with help from modern science, and instinct with expert anthropological advice. Some numbers are a testament to this unit’s success.

Over the years, since it was established in 1989, this unit has completed more than 6,500 age progression renderings, reunited more than 1,300 children with their families, put together 516 facial reconstructions — 198 on skeletal remains and 318 on soft tissue from morgue photographs and medical examiner observations — and provided 100 identifications.

For Mr. McNally, however, the numbers aren’t the story. The children are. Getting them back is the ultimate goal. But when that isn’t possible from the start, he’ll settle for getting a mother or a father and a family some answers, through identification. This is the story of NCMEC’s artistic warriors, the details of their forensic work, their thinking, and their calling, as he sees it, through their unit chief’s eyes.

Interviewer: We’d like to start with the basics. For the sake of our readers, what exactly is a forensic artist? Most people that follow law and order shows associate forensic artists with police sketch artists. Is there a difference and what is the difference?

CM: Forensic artists do fall under the umbrella of police sketch artists. In addition, they can be forensic anthropologists, or people with forensic science backgrounds. Basically, a forensic artist is someone that works in law enforcement, or assists law enforcement in creating images that can assist in identification. When you’re talking about a police sketch artist, you’re talking about somebody that’s actually sitting down with a witness to create a version of what this person might have looked like, in order to help in a police investigation.

When you’re talking about NCMEC, you’re dealing with four artists, Paloma Galzi, Christi Andrews, Joe Mullins and me, that are working full-time to create age progression renderings for long-term missing children, and also doing facial reconstruction on the unidentified remains of children. We’re not the only people that create age progressions but we’re unique in that we’re the only people that create them for children. The FBI, for instance, has forensic artists that are creating age progressions, but they deal mainly with fugitives, or age progressions of terrorists, or facial reconstructions of unidentified adult remains.

Just to clarify matters here, you don’t do just age progression renderings.

Correct. The age progressions are of children that have been missing at least two years. We update those every two years up to the age of 18, depending on the family’s preference, after which we update them every five years. We also create facial reconstructions from unidentified remains we may receive. We may receive photographs from medical examiners of morgue photos of children, or skeletal remains. In the second case, we’ll do a three-dimensional reconstruction from the remains. Basically, NCMEC and other forensic artists around the country don’t deal with active investigations; we create tools that can assist in those investigations.

The Supervisor, Forensic Imaging Unit, NCMEC, Colin McNally, Works on Facial Reconstruction. This video has been made available courtesy NCMEC, and has been edited. The full video can be seen here.

You deal only with long-term cases?

Yes, any case that my unit deals with has to be that of a child that has been missing for at least two years. So they are still active cases, even though we aren’t doing the investigating itself. We receive photographs of the children and family members, and these are our greatest tools for creating the age progression. We then base our rendition on the images we receive. Once our images are done, we send them off to law enforcement. There’s a method for this, it goes via the case management system and the case manager that deals directly with the family; we don’t directly deal with them either.

What is the background of your team?

I majored in fine arts in college, and growing up, I had a graphic design background. I started at NCMEC a week after finishing college and have been here 9 years —that’s pretty similar to the other artists. Once we begin here, we receive training in more of the scientific and anthropological aspects of the forensic art field. We’ve trained at the FBI Imaging Lab in Quantico, Virginia — it’s an interconnected community of forensic artists all doing the same thing — and we’ve traveled to the University of Dundee in Scotland, which is one of the only places in the world where you can get a MSc in Forensic Art & Facial Identification. There, we’ve trained with the Masters’ degree candidates, and learned their techniques.

We’ve also been fortunate enough, through NCMEC, to go to different trainings annually, and been able to consult with anthropologists, many of who volunteer their time and expertise with us on cases. One in particular, from the Natural History Museum in DC, Dr. David Hunt, is a Board Certified Forensic Anthropologist, who’s helped us out on about 300 cases, where he gives us assessments of skeletal remains. He has been a huge help. I can’t emphasize enough how invaluable his expertise has been, and he’s done this for free, because he wants to give back to the community. Having that expertise, and combining that with the artistic skill that the four of us have, is what makes this work — it really is a collaborative effort.

What made you — any of you, really, decide you wanted to join NCMEC one week after college? It’s not a typical career path, to go straight into working on missing children cases.

As a junior in college, I learned about the work NCMEC did from the former supervisor of a law enforcement forensic imaging unit, who was a neighbor of my parents. He didn’t know I was interested in art, and while I knew he was a cop at one point, I didn’t quite know what he did. I later got to talk to him, and he introduced me to NCMEC’s Forensic Imaging Unit and the work they were doing. Till that point, my education on age progression renderings was based on television shows.

I wasn’t prepared for the fact that artists were actually doing this work, or that it was a manual process. I assumed, like most people, that it was all automated, much like you see on CSI or Bones. My parents’ neighbor brought me into the office in Alexandria and introduced me to everyone. I was on a path to go into something more mainstream. But once I saw the work that was being done by forensic artists, I made it a point to at least apply for a job here, I’d learned that they would be hiring later, when I was a senior. I was fortunate to get the job, and took over as unit supervisor a year-and-a-half ago.

So the passion came later.

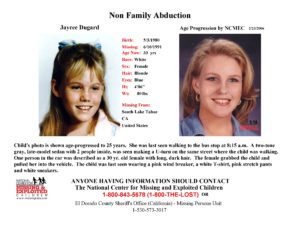

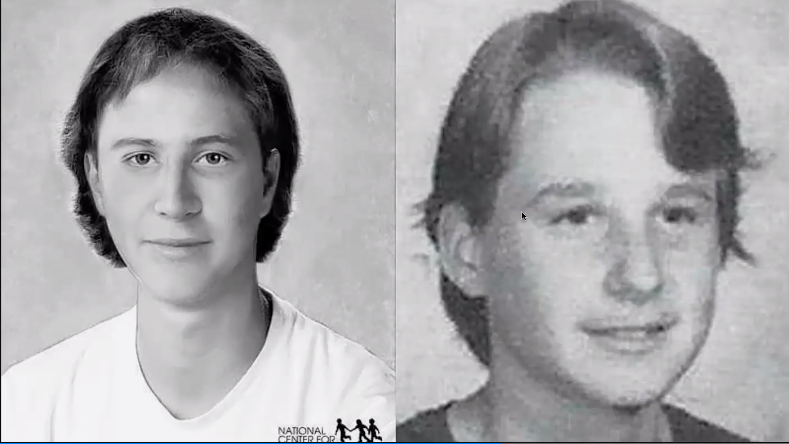

You can’t be here and not understand what an amazing opportunity this is to make a difference, but the passion really kicked in a couple of months after I joined work in June 2009. In August 2009, Jaycee Dugard was recovered. She was a long-term missing child, held captive for 18 years, and I got to see the age progression that was created of her. It was a story that was highly publicized. Getting to see how close the age progression came, a rendering that was based on the work of Joe Mullins, the artist I had been learning from those first two months, and getting to see firsthand that it really did work, this process and this technology we used, that was incredible!

National Center for Missing & Exploited Children’s forensic artist, Joe Mullins, at work on an age progression of Jaycee Dugard in February 2006. Dugard was abducted at age 11 in August 1991 and recovered at age 29, in August 2009. Mullins’s age progression images, which were based on 15-year-old photographs of her at age 11, bore a remarkable resemblance to the adult Jaycee. You can see the resemblance in a 2015 CBS17 30-second news clip here. This video is courtesy, NCMEC.

It made it all real?

It did. And it wasn’t even that it was my work, it was the work of all of these people, the case manager, the person at the call center that took the initial call 18 years earlier — getting to see their reaction when they heard the news of her being recovered, and then getting to see how close the image was.

It’s really hard to describe but my passion really kicked in from that case, and then it went into overdrive when I started seeing identifications and recoveries from the work I had done. I was fortunate enough, maybe a year or two years into working, to do an age progression of a child who had been missing for 40 years. The child was obviously an adult when he was recovered at age 42, but he was recovered. As far as I know, that’s one of the biggest gaps there’s been, in terms of missing person recoveries based on age progression renderings.

Age progression technology predicts what an individual may look like years after they go missing. How exactly do you predict that? You’ve said it’s a mix of art and science, I assume you mean in the latter sense of both technology and genetics. Could you be more specific?

I’ll start with how we intake the cases first, because I think that will give you an idea of where we begin our work. As I’d mentioned, a child is eligible for an age progression image after he or she has been missing for at least 2 years. The reason for that 2-year gap is because a child’s face is going to grow and develop, and therefore, that original photo that people work off would be outdated — in effect, an inaccurate portrayal of what the child looks like today. So we create these age progressions to give the public as best of an idea as possible of what this child may currently look like.

The way we’re able to do that is by getting as many photographs as possible of the child from as close as possible to the time they went missing, as well as photographs of family members at the target age we’re going to age progress the child. So hypothetically, if we have a 2-year-old, who is 6-years-old when we’re doing the age progression, we want to see photos of the parents, any biological family members, older siblings, grandparents, aunts, uncles, whatever we can get, at the age the child went missing, as well as the target age. In this case, for instance, we’d be looking at the parents at age 2, and the parents at age 6.

Why we talk about it being art and science is because while we do talk about biological similarities between family members, which is science, it is more art than science in the sense that it is subjective on the part of each artist to determine the commonalities between each family member. In addition, we’re using an artistic program to create artistic renditions of what the child would look like. We’re using Adobe Photoshop, off the shelf Photoshop, and we’re photo-compositing images of these children and family members to create the age progression. Though we use aspects we see in the genealogy and biology of the family, and have an understanding of how the human face grows and develops based on different ancestries, we use artistic determinants to create age progressions.

Diversity Matters

How hard is it when you have a missing child from more than one race or ethnicity or ancestry? For instance, my husband is White, of English and German ancestry. I’m Asian, of Indian origin. Our daughter’s skin color is more like my husband’s, her eyes and features are like mine. She’s clearly a mix of us both. But I have relatives and friends, interracial couples, where one side’s genes have clearly dominated in their child, but it’s not always evident by 12 months or age two.

The difficulty in doing an age progression is always in the starting point, in how young the child is. Take your daughter, for example: If we’re dealing with a picture of your daughter at age 1, as opposed to age 10. By age 10, she’s going to have many uniquely developed characteristics in her face that will show what she has in common with you and your husband — things that are really difficult to determine when a child is very young. That’s why we try to get the parents’ actual written feedback.

We might not see it in an image, but when a searching mother tells us in an email or a phone call: “My child shares my nose, my husband’s eyes, and I think their hair is going to be this texture, you may not see it in the photograph, but I think it will turn out this way,” we listen. I think the best way to explain this is by saying we’re not the experts on a child’s face, the parents are. Admixtures are only as difficult as the photographs we receive. Forensic artists are of the opinion that we need as many photographs as possible. In my experience, no matter what the mixture of ancestry, we can complete an accurate age progression.

Is this something you’re seeing more often, as the U.S. population gets more diverse?

Yes, it’s something we see on a regular basis because of the diversity in our population. The one thing that is difficult though, in this regard, with a child of two or more races, is when we do a facial reconstruction from skeletal remains. We do consult with anthropologists on this and receive an assessment based on those skeletal remains, but keep in mind that an anthropologist is just looking at the skull. In some of these cases, unfortunately, we’re looking at very young children. That’s when these admixtures or mixed ancestries can make things very difficult, because it’s hard to tell from a skull, especially that of a young child, what features are going to be prominent; like when a child is a mixture of African and Asian ancestry.

Many of us are readers of crime fiction, and we’ve always been told that bones tell a detailed story. What do you do when they don’t quite tell that story, or the story is much more complicated because of mixed ancestry thrown into the mix?

They still tell a story, it’s just different. It can be very difficult, but working with people like Dr. David Hunt, he’s never going to give us feedback or an assessment that he’s not confident in. He’s going to give us the best assessment possible, whatever he can — he’s good at predicting things like age. Then, he uses dentition, how the teeth are developing, and the skull to determine the approximate admixture or race, and he bases that on different contours and different parts of the anatomy of the skull. He’s able to see things that are indicative of different ancestries, and how those things combine together in the skull to determine what that child’s admixture or ancestry could be. It really depends on the case.

[Editor’s Note: Dr. Hunt is one of the world’s best known physical and forensic anthropologists, and is in charge of the “Bone Collection” — or more technically, the Physical Anthropology Collections Manager — overseeing more than 30,000 cataloged human remains at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington, DC. He is active in forensic consultation to the Northern Virginia Medical Examiner’s Offices as well as NCMEC. The information in the above audio clip was sourced from a Smithsonian Magazine article by Michael Kernan. You can read the whole piece here].

Why ‘Social’ Changed It All

How long does it typically take to complete an image or rendering and what does it depend on? What do you do when there’s a dearth of source material — all of what you’ve told me so far indicates that you’re dependent on the material you get, the images, the feedback etc. What do you do when you lack that?

It takes approximately eight hours to do one age progression composite image — one full workday, with no interruptions.

That seems like a very short time!

We’ve got it down to where once we actually begin creating the image itself, that’s about how much time it takes. The reason for that is that there’s a huge amount of work that comes through this unit, and we’re only four artists. The process does depend on the images we receive — so we couldn’t really do the work if we didn’t have source material. Sometimes, if we get a lot of material, that process might take longer because we tend to study the material longer, in order to be more accurate. Once we complete an age progression, we give it to the case manager, who will submit it to a family for approval.

Just to clarify, the actual image creation process takes about eight hours or so, this doesn’t include time spent on studying all the material and researching anything you need?

Yes, basically. We say eight hours of working time, but the whole process in itself depends on the images.

You don’t speak to the families?

No. The feedback comes through the case manager. When a family member of a missing child decides that they want an age progression done — and do note that this isn’t mandatory, it is a choice they make and we offer this as a free service to them — they are assigned a case manager. That manager talks to them and emails with them and then submits the request to have the age progression done on behalf of the parents to us.

What happens when it’s done?

Before the parents even receive the rendition of the age progression, they receive a cover letter, an explanation of what they’re about to see. For most parents, it can be traumatic to see what their child could look like; years after they’ve disappeared or been missing, especially when they’ve been looking for their child through this time. There is often feedback from the family because it’s difficult for them to see their child’s face created by an artist. If we had to sit down and talk to every family, it would make our work very difficult.

I’ve spoken to parents on rare occasions. I have utmost respect for the law enforcement officers and case managers that talk to parents going through the unimaginable pain of not knowing where their child is. However, from my perspective, I don’t think speaking with parents would make my job easier — I need to focus on the details of a child’s face. We do get emotionally invested in all our cases, and have the numbers to prove that these can be accurate renditions of what these children could look like. That is where our focus has to be — on telling that piece of the story.

What tools do you use? And how much technology do you use? Is it always 2D because of posters?

For age progression, it’s always two-dimensional. We use Adobe Photoshop to create age progression renderings, but when actually doing the work, we use a Cintiq Monitor, made by a company called Wacom. Basically this monitor allows us to draw on the surface of a screen, so for us, it allows us to feel like we’re using a pencil and paper and drawing. That’s the extent of the tech for creating the age progression itself. But I can’t emphasize enough how important it’s been to have the technology that led to people having cameras on every phone, or to Facebook and Instagram.

Before camera phones, before social media, we’d often have hard copies sent in; we’d have to be careful about sending them back to families. Now, as far as reference photos go, we have all these social media accounts, and everyone has a million pictures of their kids on their smartphones and pictures of themselves. Just the ability to take a selfie has changed so much for us, and social media has been a huge benefit from the point of view of creating an accurate age progression. It makes it so that there usually isn’t a dearth of family reference photographs.

It’s interesting you say that. Three months ago, Biometrica ran a piece with Caroline Humer from ICMEC, the International Centre for Missing and Exploited Children. One of the issues we discussed was online grooming, which is a problem because of the growth of social media and access to social media by children, on one hand, and by anonymous predators on the other, so it’s all a balance, isn’t it?

[Editor’s Note: ICMEC is a NCMEC affiliate focused on the global response aspect to child abduction and exploitation, while NCMEC is focused within the United States.]

It is that, absolutely. From our perspective though, social media has been invaluable, not just as reference material, but also because of things like when people re-post missing children information. Every now and then, when I scroll down my newsfeed on Facebook, I’ll get a posting from NCMEC, a poster with an age progression rendering, where you’ll get a link to click to learn more about the case. There may be something from our Facebook page on unidentified reconstructions we’ve worked on, and people in the public from all over the world can see these cases and help — it’s a huge benefit.

It Takes A Spark

It is. You update the posters every 2 years till a child turns 18 and then every 5 years after that. How hard is that process, at two levels:

- First from a work perspective, in terms of developmental changes that occur as a child grows up in a potentially very different environment. For instance, they may have had no proper dental work while missing, or be malnourished, both of which may cause major changes in appearance. They may have been abused; be on the streets, homeless, or on drugs, which might cause other changes in appearance.

- Second, how hard is it from an emotional and intellectual perspective, as time goes on and a child hasn’t been found?

Creating the images of these children over the years does get more difficult as the years go by and they aren’t found. As forensic artists, we don’t want to take the liberty of imagining the kind of environment these children may be living in. We don’t know if they are smoking or doing drugs, we don’t know if they are malnourished or abused or what their diet might be. We have to create these images on average; we have to create them with the mindset that there needs to be something in a face that will spark recognition.

6-week-old Aric Austin was kidnapped by his father on December 20, 1981, in Vancouver, Washington. 22 years later, a Department of Education investigator was investigating a man named Michael Johnson for reportedly falsifying information on government-secured student loans, something he discovered when the birth certificate of Johnson’s alleged son raised red flags. When they interviewed the son, his face sparked a memory and the investigator contacted NCMEC. The age progression of Austin quite closely matched the way he looked. Shortly thereafter, Aric Austin was reunited with his mother and siblings, 22 years after he first went missing. All images courtesy, NCMEC.

We’ve always maintained that it’s not necessary to create a 100% accurate portrait, that’s not going to happen, it is important to create a rendition that will spark recognition with the public and potentially lead to a child being found. It’s impossible for us to know what a missing child’s lifestyle will be like; what we try to do is emphasize to case managers and families that if there are any tips or leads that give an indication of a lifestyle, we’ll take that into consideration.

If they had been smokers or done drugs, the family dental history, if there was a history of obesity, it depends on each case with these images. But we basically work on an average, and we don’t want to take too many liberties. Another huge issue we might have is with runaways — they might dye their hair different colors, get piercings, we try to work with the case manager to get any details we can on how we should portray these children.

Do you provide different image options to the families?

We have in the past. We then leave it up to the case manager and family to decide which one to put out to the public. But we emphasize that we put out only one.

Why is that?

If you think about the people in general that look at these age progressions, at most, they’d look at these renditions for a minute or two and then move on with their day. You don’t want multiple images of a child taking up too much time or space; you need the people looking at them to focus. You don’t want these images to become a blind spot. While we have created versions of a child wearing glasses and not wearing glasses, or, if a child is male and older, done images of him with and without facial hair, we’ve then left it to the family or law enforcement to decide which one to go with publicly.

Have you ever created an image of a potential abductor?

Absolutely. Especially if it’s a family abduction, we’d create that as we would any age progression.

I thought you did worked only on images of children.

It is mostly children, but not just children, it could be adults who have abducted children or committed crimes against children. We don’t necessarily consider that our regular workload because the cases are few and far between, but we’ve done quite a few over the years.

Quick question. When does the case get to law enforcement from your end?

After the family approves the case, it goes through the process of getting through our case management support system, and then it goes to law enforcement. Law enforcement can then create a local or national news campaign. The family has the ability to do the same, and sometimes NCMEC gets involved, depending on the case, or if there is something like an anniversary of a missing child. First and foremost it goes on our website, missingkids.org.

NCMEC forensic artist Christi Andrews works on an age progression rendering of Tammy Flores in 2013. Tammy is believed to have been abducted, along with her younger brother, Diego, by their non-custodial father, Francisco Flores, in October 2007. Video courtesy, NCMEC.

Going on from this same question, you’re as much first responders as law enforcement, firefighters or EMTs, along with your case managers. You provide an invaluable service, you work on the front lines and you work with children and families that have been traumatized, and are living their worst nightmares. It’s bound to take an emotional toll.

How hard is it to work in this field and community day in and day out, to maintain the professional and emotional investment needed to create a unique likeness, yet have enough of an emotional detachment to move to the next case, because you have to, irrespective of whether a child has been found or not? Likewise, how do you revisit that case 2 years later or 5 years later? Do forensic artists get PTSD and do they burn out?

Speaking from my own experience, yes. I have dealt with cases that I haven’t been able to forget over the years. NCMEC is tremendous in providing support. Therapy is provided to employees that would like to use it, which I have. I found my biggest support system through working here has been talking with other employees that have worked in law enforcement for 30 years and now work at NCMEC as a second career. Being able to share stories on how things impact you really help when you’re working with a long-term missing child case that comes up every 2 or 5 years, or when you’re dealing with a deceased child with heavy trauma to their face. Sometimes when there is a very young child, it’s very hard.

It’s also always difficult when you’re working on unidentified remains, because you know whatever you do, you’re not going to be able to bring this child home to their family. It’s a very emotional job, but getting to speak with other members of NCMEC, and seeing the art I’ve been doing my whole life being applied to something positive to help families reunite, helps make up for the emotional toll that some cases do take from time to time.

I don’t have children; I plan to some day. But I know that for those that are parents and work here at NCMEC, it’s much harder. Two of my forensic artists have children, and I know that for them, you can definitely see it’s different when they work on some cases. It is a draining job but the positive impact does make up.

Have you ever thought about quitting?

Honestly, never. There are other forensic art jobs out there, but I really did find my passion and my calling with this work. I still consider myself lucky to be here, to have found this. I thank my former supervisor who took a chance on me, and a friend who encouraged me to pursue it.

Have you ever had to deal with threats when a child hasn’t been found? Sometimes, when families are facing the worst times of their lives, and they’re emotionally overwrought, they’re not always rational and are looking to blame someone, or something. Has that ever been directed at you or other artists or your case managers?

I can’t say I or the other artists have ever received a threat, but I can say we’ve received criticism. It’s completely understandable. Families go through the process of grief differently and the process of coping differently. Some are very positive in the way they respond to an age progression, and some are not. It’s definitely rare, but we have had cases where a family has been openly negative about a rendition. They have then suggested what we can do to improve it, we go ahead and make the adjustment, and then there’s a whole other list of adjustments. At that point, we realize that some parents may just not be capable of seeing what this version of their child would look like today, because they have their mind set on what their child was like at the time of their disappearance. Seeing an artistic rendering of the child in the now is too traumatic for them.

So it’s an inability to cope?

That’s what we think, from an artist’s perspective and having dealt with innumerable cases of families of missing children. But I’m not an expert in the psychology of parents or parents that are grieving. However, I do know one thing, the other artists and I are all so open to this criticism and ready to make adjustments — we understand where it’s coming from and we want to help. But at some point, we have to limit the number of adjustments we make with an age progression and move to other cases.

We have the fortunate capabilities of case managers that are really good with dealing with cases, we also have Team HOPE, a support system of parents of missing and sexually exploited children that have come together as trained volunteers under the aegis of NCMEC, to act as a support system to other parents. This also includes families that have recovered children, and they’re able to explain how age progression works. We also have a family advocacy division that will help, so there are different support systems in place. This work does have to come with a thick skin. You have to emphasize this is not intended as a portrait you can frame and put up on your wall. It is a tool for law enforcement and the public to spark recognition, a tool that can assist in the investigation, and they have to see it that way.

There was a piece in Forensic Magazine about the case of James Allen Reymer, an Illinois teenager who went missing in 1983. He was finally connected, through a forensic reconstruction you put together in 2013 from old morgue photographs, to a body that was found in early 1984. After he was identified, you said, “It makes us feel like we have the best job in the world.” “You get a case like this, and it starts off as a sad story — and you provide answers to the family that’s been searching, in many cases. You get the child their name back.” Could you reconstruct that case for us?

I remember that case very well. That was from a photograph but it was almost like doing a skull reconstruction, because of the nature of the incident. It was a gunshot, straight to the face, heavy trauma, no recognizable facial features. I was basically looking at the child’s skull with 80% of the facial features missing. I was trying to follow the features of the child’s skull and fortunately, the child was of an age where there was a lot of uniqueness in the skull.

I could see things like the steepled nasal aperture, I could see that this child would have a relatively narrow nose, I could see what the projection of this child’s nose would be like, what the tip of the nose would be like. It was difficult to see what the mouth would like because the amount of information on the photo, so there were parts of the image I could do an accurate portrayal on, because I had a good view of the orbits. So for me, because of the time period, during when the unidentified child was approximately alive, I was able to incorporate the hairstyle into the reconstruction. When it was created, it was out there in the public for a few years before the child was identified and I was pretty blown away at what the child actually looked like, compared to the rendition.

It was one of my favorite cases. I still remember the day that I found out, I was really blown away. I thought he was identified because of something else. I thought perhaps that it was the DNA that identified him, I didn’t realize it was because of the reconstruction. It wasn’t bringing home a child to a family, but in a case like this, it was providing answers to a mother that had been looking.

How often do you or your team revisit cases like these? A recent piece in Evidence Technology Magazine by NCMEC president and CEO John F. Clark talked about what he called the “John Parker Doe case.” He stated your team has done 516 facial reconstructions, and provided 100 identifications so far. In this case, this was the unidentified remains of a white male, believed to have been between 15-20 years old, originally found in 1985 in the Dallas-Fort Worth area. The case was revisited in 2012 by NCMEC Forensic Services Unit’s Project ALERT (America’s Law Enforcement Retiree Team) volunteers, which eventually led to your team receiving a CT-scan of the skull.

The piece also talked about how you’d be able to do this facial reconstruction in color, because of a new partnership between NCMEC and a Reston-based company called Parabon NanoLabs, and a process they’d developed called Snapshot DNA Phenotyping. The article said it uses DNA, in this case extracted from skeletal remains, to determine traits, including eye, hair, and skin color, facial features, any freckling, and ancestry. Could you elaborate on the technology changes that potentially lie ahead?

This was the first case that we’d worked on with Parabon. It was based on a request from the ME of a Texas County. They reached out to us to update a facial reconstruction. We had been working on this developing partnership with Parabon because of their technology advancements and use of genealogy to apply color palettes to facial reconstruction, not just color palettes — things like hair color, skin tone, eye color, and freckling in the face.

You’ve talked about how important it is to do this work manually, and been focused on doing this layer by layer. How comfortable is it bringing in technology to do some of this work and where is this going, whatever the technology?

It is different. We’ve been used to working with anthropologists and we’ve been successful working with them. Sometimes algorithms might go against what the experience of an anthropologist says or has noted in an assessment, so some of this is new ground and there is a balance to be found. For me, and really every part of NCMEC, we’re very comfortable with embracing new technology in the hope it will work. We think new tech will make it all more accurate, but it’s a matter of finding out and building trust through a process. I trust the tech that Parabon, for instance, has shown us, I just wish I understood it a little better.

I do have to note, though, that when I did the facial reconstruction, I used the manual process that involved working with an anthropologist and getting an assessment done through the traditional method. I used Parabon for applying the color. I think it can be hugely beneficial if it ends up working because, simply put, I think the public at large is drawn to color images, and it can be effective. We’re currently involved in conversation on a second case, so we’re hopeful this will go well.

John Parker Doe hasn’t been identified yet though?

No, not yet.

There have been other companies that have said they use tech to do age progression online; you primarily use human intelligence, intuition and ability. I know that in our field, with facial recognition, it’s always a combination of machine and human intelligence to give you an answer; whatever Hollywood and TV shows tell you, it isn’t automatic. What does the future hold? What do you think, for instance, of a University of Washington study from a few years ago, which said it could predict and create age progression algorithmically? Where do you think all of this is going?

I did actually hear about that study — my supervisor at the time had reached out to the University of Washington and said we would be interested in meeting with them. I don’t think there was any follow-up from their end. As I’d mentioned, we’re very interested in new technology and anything that can make the process of finding missing children easier or faster. The reason we don’t use automated aging software is because of the nature of the images we receive, the pixilation quality, or sometimes the children are very young.

Carlina White was 19 days old when she was kidnapped by a woman posing as a nurse at the Harlem Hospital Center in Manhattan. She was raised as Nejdra “Netty” Nance by the woman, Annugetta “Ann” Pettway. At age 23, she became suspicious of the circumstances of her birth, and went on to solve her own case by going on to NCMEC’s website, finding the age progression renderings of herself, and calling their hotline. Her case is believed to be the longest-known gap in a non-parental abduction, where a victim was reunited with the family. Images and poster of Carlina White courtesy, NCMEC.

Could you elaborate?

Sometimes, the children are only a few months old, or younger, if they’re taken from a hospital. There’s no software I know of that can take an infant’s photograph and accurately portray it as a 10-year-old, or take unique facial features from family members and manually manipulate them in a way that can render them into a portrait that can be an effective tool for investigation or spark public memory. A forensic artist can do that. I think there’s a middle ground though, by potentially using facial recognition technology, and running our age progression images against facial recognition software to see if anything comes up in a database. We’re open however, to any developing technology, if there’s anything that can truly help us find missing children faster, or identify remains and give families answers, we’d be all for trying it out in the future.

A Note About This Series

Running from mid-September to Oct. 1, the one-year anniversary of the Las Vegas shooting, this is a four-part series in lieu of the Missing & Unidentified Persons Conference (MUPC), which is skipping a year as it moves to Las Vegas for its 12th edition next year. Each piece features an expert and focuses on an aspect of law enforcement and other public safety response to missing persons and mass casualty incidents: Urban Search and Rescue; Forensic Imaging in Missing Children Cases; Investigations focused on At-Risk Communities, Including Human Trafficking; And Mass Violence and Terrorism. This is the third of the four. The fourth and final piece will run on Monday, October 1. This series is a collaboration between the NCJTC and Biometrica Systems, Inc. You can register for the 2019 MUPC here.

You can email the writer at kmurali@biometrica.com