Black. Child. Missing. Who Knows? And Who Really Cares?

By Gaétane Borders, Ed.S.

African American children make up just 14% of the under-18 U.S. population, but account for almost 40% of all reports on missing children. The search for children of color is complicated by the stark disparity in media coverage, when compared to missing white girls.

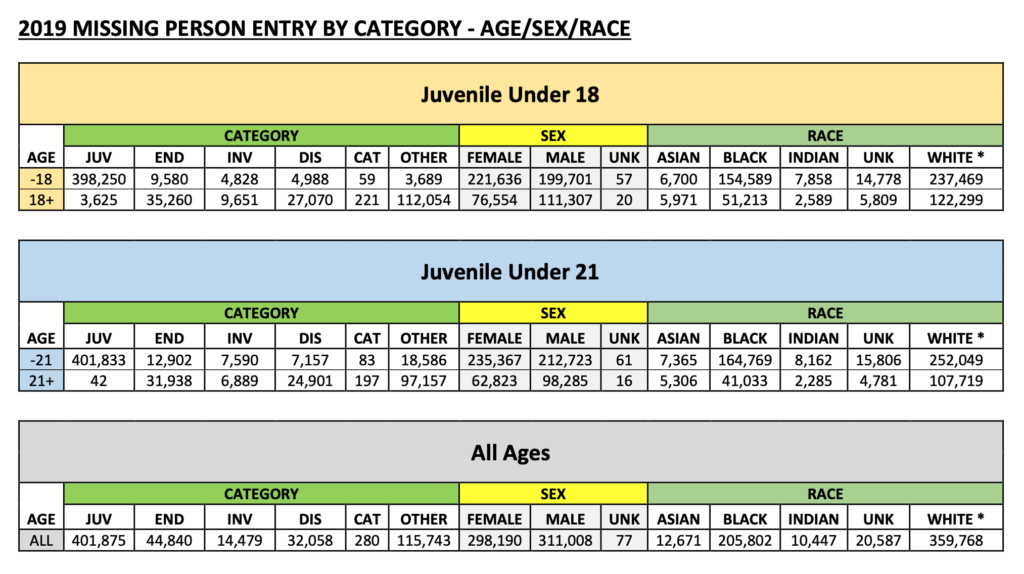

Research has shown that a child is reported missing roughly every 40 seconds, and that hundreds of thousands of children disappear each year. According to the FBI’s National Crime Information Center (NCIC), there were 421,394 entries for children under the age of 18 who were reported missing in the United States in 2019. When the 187,881 entries for missing adults was included, that number of entries for missing Americans jumped to a staggering 609,275.

The crisis of missing persons is not an unknown phenomenon. Holly Bobo, Elizabeth Smart, Natalee Holloway, and Caylee Anthony all became household names, largely due to the heavy media coverage around their disappearances. In contrast, most people are less familiar with names like Tarasha Benjamin, Raymond Green, Jessica Gutierrez, Christopher Dansby and Shane Walker, all of whom were children of color who disappeared without a trace, without the wall-to-wall media coverage that marked some of the other disappearances.

A False Narrative

This disproportionality in media attention helps create a rather subtle form of misinformation — the implication that children of color are not victimized as often as Caucasian children. However, in actuality, children of color made up more than 40% of all missing person reports in the U.S. in 2019. More specifically, African American children accounted for almost 37% of all reports on missing children under the age of 18. Given that black children make up just 14% of the under-18 U.S. population, that is a horrifying statistic — and a terribly tragic one.

Despite these numbers, the mainstream media has historically lacked diversity in its coverage of missing persons. A 2005 study by the Scripps Howard News Service noted that 162 missing children cases were reported by the Associated Press between Jan. 1, 2000, through Dec. 31, 2004. The findings were that white children accounted for 67% of the Associated Press’s missing children coverage, and 76% of CNN’s. However, white children represented just 53% of the 37,665 cases reported to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC). Conversely, black children accounted for only 17% of the AP’s coverage on missing children, and 13% of CNN’s, while making up 23% of cases reported to NCMEC.

A 2010 study by Pace University professor, Seong-Jae Min, and Rowan University professor, John C. Feaster, analyzed archived news segments from 2005-2007 for ABC, CBS, NBC, CNN, and Fox News. They concluded that the coverage of missing children cases was disproportionately based on race and gender. The study, “Missing Children in National News Coverage: Racial and Gender Representations of Missing Children Cases,” found that African American missing children were significantly underrepresented in news coverage when compared to national statistics. The study argued that “such things as newsroom diversity, news operation routines, media ownership, and commercial motives of media contribute to the race- and gender-related media bias.”

The “Missing White Woman Syndrome”

Dori Maynard, the late president of the Oakland-based Maynard Institute for Journalism Education, an organization with a mission to promote diversity in the news media, also shared her opinion in the report. She is quoted as saying, “Often the assumption is that the white girls are quote-unquote innocent victims, whereas with poor children or children of color, there’s some nefarious activities involved.”

Social scientists have embraced the phrase “Missing White Woman Syndrome,” one ostensibly coined by Gwen Ifill, the late PBS anchor. It essentially refers to the media’s obsession with missing or endangered young, white women, while being far less interested, at least on the surface, in cases involving missing women of color, women from socioeconomically depressed backgrounds and missing men or boys.

The plausible reason why the media discrepancy has been so prevalent is likely due to a combination of factors. What makes it difficult to successfully conclude the cause are variables such as socioeconomic status and access to resources. However, what is absolute is that media coverage helps bring awareness to the missing. It increases the possibility that the case will be solved by a recovery.

One factor that greatly improves the likelihood that a missing child will get media coverage, whether print or tv, is if they are given an AMBER Alert, the early warning system to help find abducted children. However, each state’s AMBER Alert plan includes its own criteria that must be met. The PROTECT Act, passed in 2003, calls for the DOJ to issue minimum standards or guidelines for AMBER Alerts that states can adopt voluntarily. The Department’s Guidance on Criteria for Issuing AMBER Alerts is as follows:

1. There is reasonable belief by law enforcement that an abduction has occurred.

2. The law enforcement agency believes that the child is in imminent danger of serious bodily injury or death.

3. There is enough descriptive information about the victim and the abduction for law enforcement to issue an AMBER Alert to assist in the recovery of the child.

4. The abduction is of a child aged 17 years or younger.

5. The child’s name and other critical data elements, including the Child Abduction flag, have been entered into the National Crime Information Center (NCIC) system.

Amber Isn’t Color-Friendly?

Although the AMBER Alert is a fantastic and much needed tool that helps locate children, its criteria has been criticized as being non-inclusive for children of color. One major problem is that minority children are habitually precluded from the alert because they are often labeled runaways by law enforcement. Take, for example, Jholie Moussa, who was a 16-year-old from Alexandria, Virginia, described as conscientious and a fun-loving teen. Jholie was missing 14 days before her body was found inside Woodlawn Park, Mount Vernon, less than an hour from where she lived. Law Enforcement maintained for quite some time that they did not believe that Jholie was in imminent danger. In fact, she was typified as a “typical runaway” and did not receive an AMBER Alert. Her ex-boyfriend was later charged and convicted of strangling her to death.

Phylicia Barnes is another of countless examples. She was an overachieving, young, college-bound teen with a straight A average. She vanished on December 28, 2010, while visiting family members in Baltimore. Although it was frigid the day she disappeared and her coat and boots were found at the residence, police initially labeled her as a runaway. Sadly, her body was found several months later in the Susquehanna River, and her sister’s ex-boyfriend was subsequently accused of her rape and murder.

The RILYA Alert

It is because of these systemic concerns that Peas In Their Pods Inc. (PEAS) was created in 2007. The organization’s mission is to give a voice to the families of missing children of color because they are often unsupported or recognized. Since its inception, PEAS has worked with hundreds of families, and had been a part of countless successful recoveries.

It was just a few years after the formation of Peas In Their Pods Inc. that the staff realized the discrepancy in the dissemination of AMBER Alerts and decided to take action. Capitalizing on the success and popularity of social media in 2009, the organization focused its efforts in spreading awareness by galvanizing the nation through that modality. It created an alert system called the RILYA Alert, a system that is inclusive and meets the needs of a community that had largely been ignored.

The inspiration for the name was Rilya Wilson, who was a 4-year-old child in Florida’s DCFS custody when she disappeared. She was missing for almost two years before anyone in that organization noticed. The alert is named in her honor because it is PEAS’s fundamental belief that everyone should be made aware when a child is missing, regardless of race, gender, socioeconomic status, or age. Moreover, every child should be considered a national priority once reported or labeled as a missing person.

Although the RILYA Alert gives a voice and needed attention to those who normally go ignored, there are still a few requirements:

• The abduction must be of a child age 17 years old or younger.

• The parent must have contacted law enforcement to report child missing.

• The law-enforcement agency believes the child is in imminent danger of serious bodily injury or death.

A RILYA Alert may also be issued if the child is classified as a runawayby the police. We recognize that at times, not all information is readily available (i.e., license plate numbers, name of abductor, or witness to abduction). In such cases, the available information will be reviewed and verified prior to RILYA Alert.

All children of color meeting the criteria for the AMBER Alert will also receive the RILYA Alert, since it is recognized that a significant disparity exists in how many children of color receive an AMBER Alert despite being in imminent danger. However, no missing child is excluded from receiving the RILYA Alert.

If the criteria are met, alert information is assembled for public distribution. This information may include descriptions and pictures of the missing child, the suspected abductor, and a suspected vehicle along with any other information available and valuable to identifying the child and suspect.

Community Matters, Coverage Matters

While PEAS is working diligently to help level the playing field, there is still so much that needs to be done to improve media coverage of missing minorities. The following are 5 factors that PEAS has identified as critically important in increasing the likelihood of acquiring the media’s attention:

- Families must feel supported by law enforcement when they are called upon. The tone of the officers has a great impact on how the case is handled. Looking at all of the factors before determining that a child was a runaway is paramount, since children labeled as runaways are not typically given an AMBER Alert. In turn, news outlets will not focus on these cases.

- Families must also play an active part by following-up with law enforcement and providing all clues. Families should also not wait for the media, rather they should pursue them relentlessly. Calling the news desk sometimes works. However, families will have greater success directly contacting reporters.

- Parents should hold public gatherings where family members, friends, clergy, and supporters are invited. All in attendance should hold signs with pictures of their missing loved one. The local media is often looking for a story, and having events like these helps to give the family exposure. This local exposure can also lead to national coverage as well. Typically families have no idea what to do when they find themselves in this tragic circumstance. Therefore, having the responding officers or the Detective assigned to the case share these tips with families would increase the likelihood that they will garner media attention.

- Some families have limited resources (internet, cable, phone) which makes it a definite challenge for them to either contact media, or to be contacted by media. This happens more often than not. These families need an advocate who is able to reach out to television stations and be the point of contact. Communities often have nonprofit groups that would do this at no cost. Peas In Their Pods Inc. is one such organization. (www.peasintheirpods.org).

- No change can be made without discussion. Therefore, one should not shy away from talking about this topic with others. Through this dialogue, you will likely discover that most people are unaware just how many missing children are of color. With this new knowledge, they, too, may begin to question why there is an inherent media bias. The status quo is more apt to change if more people are actively engaged in making that change a reality.

About the writer: More than 10 years ago, counselor and educator Gaétane Borders began her advocacy for the families of missing children after speaking with a mother whose three children were abducted and ultimately murdered. She heads Peas In Their Pods, Inc. PEAS was founded in 2007 to give a voice to missing children of color and their families, and to fight against child abuse and sexual exploitation. You can reach Ms. Borders on Twitter @parentingpundit. You can also write to us: marketing@biometrica.com