Frequently Asked Questions

Data FAQ

What data do you collect?

We primarily amalgamate arrest data, 100% from law enforcement sources/systems (local, state, federal, some tribal, international). We also collect some conviction data but have not, at this point, begun the process of amalgamating data from court records. Our data comes from law enforcement and is real-time, i.e. it is immediate: It updates in UMbRA — Biometrica’s equivalent of a NatCrim database — as soon as a law enforcement system updates data and makes it available as public record.

Is that, being real-time, different from other databases?

Yes. We pull in data from every jurisdiction in our database every hour.

Do you collect social media, mobile, financial, credit, property, contact tracing data?

No. Our data is 100% law enforcement-sourced only. We do not go into your social media and collect data, we do not look at property filings, credit reports, mobile phone records, license plates, or anything else except arrest and/or conviction data. If you have not been charged with a crime and arrested for it, you will not be in our database.

Where does your data come from?

Our data, as mentioned above, comes 100% from law enforcement, and is generated at the point of arrest. This data could be from:

A) JAILS: Local jails are operated by county or municipal authorities, including and not limited to sheriffs’ offices, and typically hold offenders for short periods ranging from a single day to a year.

B) PRISONS: Prisons serve as long-term confinement facilities and are only run by the 50 state governments and the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP). Prisons typically hold felons and persons with sentences of more than a year; however, the sentence length may vary by state.

C) INTEGRATED SYSTEMS: Six states have an integrated correctional system that combines jails and prisons. We have data from local/county jails, some from state prisons and some from federal law enforcement. We also have some tribal data.

Do you have all available arrest data in local jurisdictions or systems across the US?

No, we have access to data from 48 states and are in the process of amalgamating that data to make it real-time. But no one actually has data from every jurisdiction in every state, including the FBI. Even though we’re pulling data from various law enforcement systems and jurisdictions, we will not, in any case, be pulling data from every local U.S. jurisdiction; this could be for various reasons, including that that jurisdiction doesn’t have a need for any focus. For instance, all 3,142 county/county equivalents in the U.S. and 100 more in U.S. territories do not have jails and/or prisons. Just over 15% of jurisdictions actually do not have some form of incarcerated population at all. Additionally, there are some counties that have populations so small (1,000 or fewer residents as mentioned above) that it makes no sense to focus on them as yet.

INCARCERATED VS IMPRISONED VS SUPERVISED

The incarcerated population only refers to the population of inmates confined in a prison or a local jail. This number may also include halfway houses, boot camps, weekend programs, and other facilities in which individuals are locked up overnight. This is different from:

a) Those that are imprisoned, which is a reference to only those individuals that are under the jurisdiction, or legal authority, of state or federal correctional officers; AND

b) The number of adults supervised by the U.S. correctional system. The correctional population includes persons supervised in the community on probation or parole plus those incarcerated in prisons or local jails or locked up in other facilities overnight.

Arrest And Conviction Data Do Not Come From The Same Source

Law Enforcement Agencies (LEA) of different stripes at the local level (city/county/municipal authority) update arrest data, which is almost entirely digitized across the U.S. with text and facial recognition data feeds available for a large number of arrested individuals.

Conviction data comes from the courts, and lives in the prosecutorial basket. It is, for the most, textual data, not connected to facial recognition and in most cases, also not uniformly/comprehensively digitized.

Note: Law enforcement agencies may or may not update an arrest in a system to reflect the status of a case through the courts— this varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction and is largely dependent on the availability of time and manpower in that jurisdiction. If they do update it, it gets updated in our system too.

What is Raw Arrest Data in your system?

Raw arrest data is data that comes into UMbRA, our NatCrim database,from law enforcement/jail management systems. It is untouched, it is not merged, and it is just raw data, unlike what we see at the user interface level in UMbRA.

What does this mean?

Typically, a user cannot see that raw arrest data, unless they have developer access.A user sees the dataat the UI (User Interface) level. When raw arrest data comes in, it comes into the database in various forms, because different law enforcement agencies/counties/states input the data differently. Raw arrest data doesn’t have any direction or correlation, it simply existsin the form it is inputted by a law enforcement officer.

For ease of use, our software then takes that raw data, sifts through it and formats it into predetermined or preset categories: In this case, we have set those categories at the UI end as Name, Photo, Weight, Height, Race, Gender, Hair, Eye Color, Facility, Booking Date, Arrest Date, Inmate Classification, Arresting Officer, Arresting Agency, Age, Arrest Number, DOB, Charge ID, Description, Crime Type, Control Number, Arrest Code, Bond Amount. All of these details are not available on every arrest record. What is available depends on the Law Enforcement Agency concerned and what details they choose to enter.

What about Nationality?

The categories we have preset are mentioned above. Nationality is not one of those categories as it is not uniformly entered into data by law enforcement. If there are additional details law enforcement chooses to enter, we can’t always see those details at the UI end because they’re not part of the preset UI classifications; however, a developer with access to the raw data feed can see that additional data at the back end. Take Nationality, for instance. While we don’t have a classification for Nationality at the UI end,if we wanted to know how many Canadians we had in our database, that information would have to be requested from a developer who can look at the raw data and make a programmatic query.That number is unlikely to be correct, however, because most counties don’t enter Nationality data into their jail management systems.

Do you change or correct the data at all?

No. We do not manipulate or change law enforcement data in any way. We simply present it differently in the UI, for easier viewing. We may also (at this time, manually) merge different arrest records for the same individual in our NatCrim database, to allow users the ability to see multi-jurisdiction or multiple arrests in the same jurisdiction on the same page. For example, if you run a search for an individual named Christopher Columbus, who has been arrested multiple times in Madison County, MS, and then in Pinal County, Arizona, and if we’ve gotten to his record (we haven’t gotten to every record in the system as we have to see them individually to double-check they are the same individual), and merged his available arrest records for ease of viewing, you can see all his arrests in Pinal and Madison counties on the same page through the UMbRA user interface. However, you can’t see that on the raw arrest feed at the back end.

How is the data accessed?

The data can be accessed in 3 ways, depending on a user’s data access agreement.

a) Through eMotive, our continuous background checking software:An organization-authorized individual sets up a databaseof individuals being monitored via eMotive, and those datasets will run 24×7 against UMbRA and look for matches.An authorized HR/Compliance/Securityuser will be automatically notified through an encrypted alert when an individual on their dataset is a potential match to an arrested individual in UMbRA.

b) Through an UMbRA login:This also allowsa user to run a manual background check on an individual in addition to getting automatically notified of a potential arrest post-employment.

c) Through a direct API integration: An API or Application Programming Interface allows a program/device/system to connect, link with and interact with another, allowing backend systems to communicate with each other. The API is not the UI. The simple explanation is that a user (human) uses a UI to interact with software, a machine uses an API to talk to other machines/software/systems/devices. In this case, a client’s API will interact with UMbRA to pull and access raw data from UMbRA, our real-time multi-jurisdictional arrest database. How the Client sees that data later, depends on their own other integrations and UI.

Note: All UMbRA searches are tracked, as is every encrypted email notification alert sent out through eMotive.Whether that encrypted email link is opened, clicked on and acknowledged in the eMotive system is also tracked. This creation of a legally viable audit trail is mandatory to be FCRA compliant.

What is the difference between UMbRA and eMotive?

UMbRA is the overall national criminal database and search engine. eMotive is the FCRA compliant monitoring ecosystem that allows an organization or a CRA to create their own private encrypted database (of employees or contractors being monitored with their written consent). This database will “sit below” UMbRA and run against it, programmatically and automatically informing a company-authorized individual when someone on that private dataset has potentially been arrested.

What identifiers does your data contain?

We receive a range of identifiers, depending on the law enforcement jurisdiction. This includes full name, photograph, race, age at the time of arrest, DOB, zip codes, driver’s license number, full addresses, sometimes, social security number embedded in a photograph (these are typically from historical data), a partial social, tattoos or identifying marks.Law enforcement jurisdictions vary greatly in terms of what they collect and what they make available when they upload data to public record. It is not uniform across states and counties because state laws are different and no one follows uniform collection guidelines.

What does the reference to historical records mean, with regard to Social Security numbers?

From 2004 onward, it has been against federal law to put an arrested individual’s social security number on display on a public document or public platform of any type, including driver’s licenses. Section 7214 of the Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004 [42 USC 405(c)(2)(C)(vi)(II)] explicitly prohibits printing Social Security numbers on identification documents issued by motor vehicle agencies, including driver licenses and vehicle registrations. Old licenses that had them were phased out.

https://www.ssa.gov/legislation/legis_bulletin_010705.html

https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/42/405

While Court Data (conviction data, not arrest data) would likely have social security numbers attached to a file, the display part would be truncated to prevent ID theft. Additionally, it would be textual data, not with photographs, so you could have name duplication.

What about when data displays the last four digits of a Social?

For most Social Security Numbers displaying the last four digits, those aren’t identifiers. In a 9-digit ID, the first three numbers (area number) are keyed to the state in which the number was issued. The next two (group numbers) indicate the order in which the SSN was issued in each area. The last four (serial numbers) are randomly generated.

Law enforcement doesn’t uniformly collect or input social. When arrested, they ask for a driver’s license or some form of acceptable ID. Typically, if no other form of ID is accepted, the social security number is asked for, as a de facto ID.

Note:Everyone arrested may not have a social. People have the right to refuse to provide socials, and more than half the states have very specific laws to prevent identity theft, whichprevent a social security number from being shared on any platform by a public agency without end-to-end encryption and even then, the use case scenario is specific.

What about driver’s licenses?

While SSNs may not be displayed, DLs are connected to Social Security Numbers in other systems, as an individual needsa SSN in order to apply for a license at a DMV. In many places, Medicaid and Medicare benefits are tied to an ID, which is tied to a DL/State ID/SSN. In Ohio, for instance, if an organization has access to LEADS, they could, hypothetically, look up the social and marry that data. In some states, DLs are algorithmically generated from a social. Again, though, they wouldn’t be displayed.

On our part, we, as an organization, do not specifically categorize, collect, or display social security numbers or driver’s licenses.

Do you have any big picture facts on arrest or conviction data in the United States?

Not for display in the system, and that is not the intention behind our database or data collection — our focus is on amalgamating data to allow organizations to keep their employees, customers and the public at large safe beyond what is possible with a one-off background check. However, here are some facts based on BJS data.

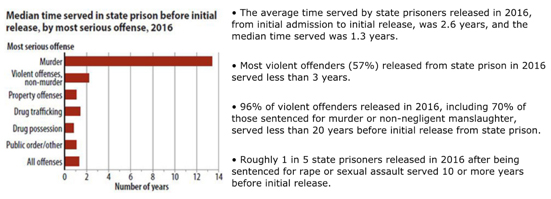

*More than half (57%) of violent offenders who were released from state prison in 2016 — the latest year for which there is complete data — served less than 3 years before their release.

* The average time an offender (general) served in state prison in 2016, from the date of first admission to initial release, was 2.6 years. The median amount of time served (the middle value in the range of time served, with 50% of offenders serving more and 50% serving less) was 1.3 years.

* Persons serving less than one year in state prison made up 40% of first releases in 2016.

* The average time served before an initial release by state prisoners who were sentenced for a violent offense was 4.7 years and the median time was 2.4 years.

* State prisoners sentenced for rape or sexual assault served an average of 6.2 years and a median time of 4.2 years before initial release.

* State prisoners serving time for drug offenses, including trafficking and possession, served an average of 22 months and a median time of 14 months before their initial release.

* About 3 in 5 offenders released after serving time for drug possession served less than 1 year before their initial release.

* In general, state prisoners served an average of 46% of their maximum sentence before their first release. Violent offenders served 54 percent of their maximum sentence, property offenders served 42 percent, drug offenders served 41 percent and public order offenders served 45 percent.

* Persons in state prison for rape or sexual assault served an average of 62 percent of their maximum sentence before initial release.

* Those in prison for drug possession served an average of 38 percent of their maximum sentence length.

FCRA FAQ

Biometrica is a technology company. What does it have to do with background checks or the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA) requirements for Consumer Reporting Agencies or CRAs?

When making personnel decisions — including hiring, retention, promotion, and reassignment — some employers run background checks. This is allowed under law.However, any time an individual’s background information is used to make an employment decision, federal laws that protect applicants and employees from discrimination have to be complied with. This includes discrimination based on race, color, national origin, sex, or religion; disability; genetic information (including family medical history); and age (40 or older), meaning you cannot check criminal background for certain employees only, everyone is entitled to be treated equally under the law. These laws are enforced by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC).In addition, when background checks are runby or through a company in the business of compiling background information, including and not limited to criminal background information, the Fair Credit Reporting Act needs to be complied with.

According to federal guidelines under the FCRA, employee background checks of different stripes are deemed“consumer reports.”The FCRA does not just regulate credit reports —it also incorporates criminal and civil records, civil lawsuits, educational and other reference checks, and any other information obtained by a consumer reporting agency.The FCRA regulates the collection and use of data obtained through these consumer reports and “promotes the accuracy, fairness, and privacy of information in the files of consumer reporting agencies.” Because Biometrica’s algorithms amalgamate real-time arrest data and make that data available to employers for the purposes of their creating pre and post-employment criminal background reports, Biometrica has to strictly abide by the provisions of the FCRA. Please note that we are FCRA compliant and an associate member of the PBSA.

Is Biometrica a CRA?

No, Biometrica is not a CRA. Biometrica is a data provider, more specifically, of real-time data-as-a-service (DaaS). Why are we not a consumer reporting agency? Because while our automated systems and algorithms provide what’s called “pointer data” to authorized clients with a subscription license in real-time (our data is updated from every jurisdiction every hour), for privacy reasons, Biometrica’s staff or contractors do not have any insight into or access to consumer data, i.e., the data of individual consumers being background checked by any organization, including their names or images.

Because of this, Biometrica staff and contractors also have no ability to conduct a background check or search on any individual consumer on behalf of a client, make a determination of a match (or not) to any criminal record, or make a recommendation on pre-adverse or adverse action. We provide that ability to our clients, once they are authorized and receive license keys.

We do provide information on FCRA compliance because it is important to our users, and because some of our users are CRAs. In the case of employee checks, we do not provide license keys till the employer signs an Employer Certification Agreement for FCRA Compliance, certifying they have complied with FCRA requirements. The Agreement details employee (this includes contractor, provider or volunteer) rights under the FCRA and requirements adhered to in order for employees to be background checked.

Our systems are HIPAA compliant, and FCRA compliant for any organization that requires adherence to FCRA guidelines.

With privacy as a foundational philosophy, we do not access any biometric templates generated during a search and allow clients to set up their systems to delete and purge biometric templates based on their requirements. If storage is mandated by law, the biometric template is stored in a black box environment and Biometrica staffers have no access to that stored data. Every event in the system has an immutable audit trail, to ensure accountability.

What is the “Notice to users of consumer reports” and a CRA’s obligations under the FCRA?

The FCRA, 15 U.S.C. 1681-1681, requires that this notice be provided to inform users of consumer reports of their legal obligations. State lawscould impose additional requirements. The text of a consumer’s rights under the FCRA is available here. Before an organization takes an adverse employment action, they must give the applicant or employee:

• A notice that includes a copy of the consumer report they relied on to make that decision; and

• A copy of “A Summary of Your Rights Under the Fair Credit Reporting Act,” which, for instance, Biometrica makes available to all its users.

How is the EEOC applicable to criminal records in employment screening or decisions?

The EEOC has no direct relevance to the use of criminal records in employment-related decisions. However, the EEOC enforces Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, which prohibits employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. According to the EEOC itself, “Having a criminal record is not listed as a protected basis in Title VII. Therefore, whether a covered employer’s reliance on a criminal record to deny employment violates Title VII depends on whether it is part of a claim of employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.”

What does EEOC Enforcement guidance in relation to an arrest note?

Enforcement Guidance on the Consideration of Arrest and Conviction Records in Employment Decisions under Title VII of the Civil Rights Actnotes the following: “The fact of an arrest does not establish that criminal conduct has occurred, and an exclusion based on an arrest, in itself, is not job related and consistent with business necessity. However, an employer may make an employment decision based on the conduct underlying an arrest if the conduct makes the individual unfit for the position in question.” Although an arrest record standing alone may not be used to deny an employment opportunity, an employer may make an employment decision based on the conduct underlying the arrest if the conduct makes the individual unfit for the position in question. The conduct, not the arrest, is relevant for employment purposes.

Further, the EEOC adds, “a conviction record will usually serve as sufficient evidence that a person engaged in particular conduct. In certain circumstances, however, there may be reasons for an employer not to rely on the conviction record alone when making an employment decision.”

What does EEOC guidelines being applied equally to criminal records mean?

When an employer treats criminal history information differently for different applicants or employees, based on their race or national origin (disparate treatment liability), it will be considered a violation of EEOC guidelines. Further, “an employer’s neutral policy (e.g., excluding applicants from employment based on certain criminal conduct) may disproportionately impact some individuals protected under Title VII, and may violate the law if not job related and consistent with business necessity (disparate impact liability).”

Please note: Compliance with other federal laws and/or regulations that conflict with Title VII is a defense to a charge of discrimination under Title VII. The EEOC enforces Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Title VII) which prohibits employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.

The FCRA notes that all users of consumer reports (in our case, employers or organizations conducting criminal background checks) should have a permissible purpose for using consumer reports. What exactly does that mean?

While consumer reports may be obtained for any number of uses, in our particular case, we focus on one: For employment purposes, including hiring and promotion decisions, where the consumer (or individual) has given written permission for the same.

How does Biometrica ensure that an employer using eMotive has informed an employee that they are being background checked post-employment?

An eMotive account is not switched on without a signed certification from employers that they will use the reports only for employment purposes that will not be in violation of federal and where applicable, state law, and attest to the following:

• That an employer has notified its employees that they are being background checked post-employment and have received written permission to get a background report on them for the same.

• That the employer will comply with the FCRA’s requirements.

• That the employer won’t discriminate against an applicant or employee, or otherwise misuse the information in a report in violation of Federal or State Equal Employment Opportunity laws or regulations.

• That an employer will provide access to information about the FCRA, including information about their responsibilities to their employees under the statute, including the notice to users of consumer reports and a summary of consumer rights under the FCRA. These are also provided at different stages through the process from the point of onboarding onward and right through the process of a report being generated. These notifications are provided in the eMotive system itself at multiple steps and are available for immediate printing for the consumer/employee in each of those steps. The HR person only needs to hit a button.

• That an employer will honor the rights of applicants and employees, including by giving them access to their files when they ask for them and conduct a reasonable investigation when they dispute the accuracy of information. Their data can be printed and is accessible and made available. All Biometrica’s data is directly 100% sourced from law enforcement, it is not collected from any other agency and there is no human interface between the time it is ingested from a LEA to the time an HR person is asked to make a determination on a possible match, it is all algorithmically generated.

What does the FCRA say about updated records?

Under the FCRA, a CRA generally may not report records of arrests that did not result in entry of a judgment of conviction, where the arrests occurred more than seven years ago.The FCRA does clarify that items of public record relating to arrests, indictments and convictions are considered up to date if the CRA reports the current public record status of the item at the time of the report. For example, the FTC has issued guidance that if a CRA reports an indictment, it must also report any dismissal or acquittal available on the public record as of the date of the report. Similarly, if a CRA reports a conviction, it must report a reversal that has occurred on appeal. Because the requirement to report complete and up-to-date information is item-specific, the report should include the current, complete, and up-to-date public record status of each individual item reported. The FTC has not indicated that a company has an obligation to continually update reports that it has already provided, but the report should be up to date at the time it is provided.

As Biometrica carries real-time data, updated on a daily basis,our records match the most current available public records for an arrest.As this is real-time, a case would not have been adjudicated by a court at that point. We also update all law enforcement updates to the case as it moves through the system, when law enforcement updates the case concerned.

Similar to the requirement for ensuring complete and up to date information, the FCRA also requires that CRAs establish and follow reasonable procedures to assure maximum possible accuracy of the information they report. How do you do this?

Algorithmically, the system first matches name and facial recognition against our 100% law enforcement-sourced multi-jurisdictional database, and then presents possible matches to a human — the company-authorized HR or compliance person — for a final determination. To elaborate, when the algorithms (machine intelligence) identify a possible match against name and facial biometric parameters, we then present an actual person (human intelligence) with all the arrested individual’s case data that the jurisdictional county makes available to us (which differs in the case of each county or county equivalent): It could be age, race, gender, height, eye color in one case, it could be age, race, gender, in another, or age, gender, height, eye color, hair color in yet another. The final determination of a match between an employee and an arrested individual is not made by Biometrica directly or indirectly, through AI or humans; it is made by the employeror client company who know the employee best, and who are best placed to decide what to do with the information they have. Our obligation is to comply with the law, provide them with the data, and remind them of their obligations at every stage under the law, including the obligation to provide the employee with a copy of their consumer report.

What happens in case of an adverse actions based on information obtained in the report?

If an employer chooses to take any type of adverse action, as defined by the FCRA, and that action is based at least in some part on information contained in a report generated from eMotive data, Section 615(a) requires the employer to notify the employee. We recommend that is done as a matter of course. The notification may be done in writing, orally, or by electronic means, and must include the following information:

• The name, address, and contact information for Biometrica.

• A statement that Biometrica did not make the adverse decision and is not able to explain why the decision was made.

• A statement setting forth the individual’s right to obtain a free disclosure of their file from Biometrica, if the request is made within 60 days.

Please note, as mentioned above, we provide the means to print notifications and reports in seconds. Arrest reports include case file numbers of arrested individuals, and we would strongly recommend that in the case of an HR person determining a positive match to an employee, they follow up with the law enforcement jurisdiction concerned prior to determining further action.

What of the responsibility to send notices to affected individuals?

Please note that no Biometrica employee or algorithm is making the final determination of a match between an employee and an arrested individual, that determination is being made by an organization’s authorized HR or Compliance personnel. As Biometrica is not making any determination, it is not required to provide notice directly to any individual,as long as Biometrica maintains strict procedures designed to ensure that the data is complete and up to date, which, as the data is real-time, is up to date.

However, notice IS required when a client company takes an adverse action against an employee based in some part on the information contained in the eMotive report, and Biometrica provides the means for an employer to generate a consumer report with details, for the employee’s benefit.We also alert employersto this responsibility at different stages within the system itself, with access to the notice to users of consumer reports.

What language does eMotive include for the benefit of users?

All eMotive users will find the following language included in their systems at different places: “As the authorized person for your employer, you have received this report on a match candidate based on several algorithmically generated demographic parameters. These have been based on comparisons run between individuals in the data set you have entered into the system with their permission, and real time law enforcement-sourced arrest data. However, the final determination of a possible match is your decision. If you determine that the individual is a match and you take action with respect to this individual based on this determination, the individual has a right to be informed of this determination and this record should be made available to them. Please refer to the statement of individual rights for more information.”

eMotive systems also include a notification at the bottom of each report. What does it say?

“These are law enforcement-sourced records in our system that are each a potential match to an individual in your database, pending a final determination by you. These notifications should be used for informational purposes only. You should follow up with the law enforcement body or court in that jurisdiction for further details. If you determine that the individual is a match, and you take action with respect to this individual based on this determination, the individual has a right to be informed of this determination and this record should be made available to them. Please refer to the statement of individual rights for more information.”

Does anyone at Biometrica make any changes to data sourced from law enforcement? Who can add data to UMbRA, the database against which eMotive background checks run?

No one from Biometrica can add arrest or conviction data to UMbRA. The only person who has the ability to enter data into the system is a law enforcement officer. It is entered into a jurisdiction’s jail system and our programs pull it directly from those systems. As mentioned above, there is no human interface at our end, this process is documented in our internal documents, as required under FCRA.

Note: UMbRA, our NatCrim database, and its app,DO NOT collect information about a user’s friends, contacts, or other third-party persons with or without the knowledge or consent of those parties. Our app does not collect a user’s (or their friends, contacts etc.) imagery, including and not limited to eye color, height, race, and other personal information.

This version of the app is ONLY for law enforcement usage, not for public use, and does allow a verified law enforcement official only to upload information on an already arrested or convicted individual, including details of eye color, hair color, height etc. This is standard practice for local, state, tribal, federal or international law enforcement and has been mandated by U.S. Congress. The National Prisoner Statistics (NPS) data collection program was started in 1926 in response to a congressional mandate to gather information on incarcerated individuals. Originally under the aegis of the U.S. Census Bureau, the collection of statistics moved to the Bureau of Prisons in 1950, and then to the National Criminal Justice Information and Statistics Service in 1971. This was the predecessor of the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS), which was established in 1979.

Under the National Corrections Reporting Program (begun in 1983), offender-level administrative data has been collected annually on prison admissions and releases, yearend custody populations, and parole entries and discharges in participating jurisdictions. In addition, “demographic information, conviction offenses, sentence length, minimum time to be served, credited jail time, type of admission, type of release, and time served are collected from individual prisoner records.”

NIST, the National Institute for Standards and Technology, publishes the “American National Standard for Information Systems — Data Format for the Interchange of Fingerprint Facial, & Other Biometric Information.” It states: “Various levels of law enforcement and related criminal justice agencies as well as identity management organizations procure equipment and systems intended to facilitate the determination of the personal identity of a subject from fingerprint, palm, facial (mugshot), or other biometric information (including iris data). To effectively exchange identification data across jurisdictional lines or between dissimilar systems made by different manufacturers, a standard is needed to specify a common format for the data exchange. To this end, this standard has been developed.”

Who defines the standards for the data that is entered into jail management systems?

Section 1 of the American National Standard — Data Format for the Interchange of Fingerprint, Facial, & Other Biometric Information — defines the standard for the content, format, and units of measurement for the electronic exchange of fingerprint, palm print, plantar, facial/mugshot, scar, mark & tattoo (SMT), iris, deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), and other biometric sample and forensic information that may be used in the identification or verification process of a subject. It further states, “The information consists of a variety of mandatory and optional items. This information is primarily intended for interchange among criminal justice administrations or organizations that rely on automated identification systems or use other biometric and image data for identification purposes.” Please note, there are differences in the uploaded data, depending on a law enforcement body’s state/local jurisdiction because of the practice of allowing mandatory and optional items.”

Note: While, as mentioned above, the data uploaded through and in this app is intended to be entered in only by authorized law enforcement officers and other criminal justice agency professionals, and all of this data is still a matter of public record, the app is not intended for use for the general public. Information compiled and formatted in accordance with this standard can be recorded on machine-readable media or be transmitted by data communication facilities.

Section 8.2 defines user-defined descriptive text records and states: “This record may include such information as the state or FBI numbers, physical characteristics, demographic data, and the subject’s criminal history.”

Section 8.10.26 and 8.10.27 define the collection of eye and hair color, respectively, in a SAP (Subject Acquisition Profile) and further detail the guidelines and parameters for inputting eye and hair color in the SAP, including codes. See below.

Table 23 Eye color codes

| Eye color attribute | Attribute code |

|---|---|

| Black | BLK |

| Blue | BLU |

| Brown | BRO |

| Gray | ARY |

| Green | GRN |

| Hazel | HAZ |

| Maroon | MAR |

| Multicolored | MUL |

| Pink | PNK |

| Unknown | XXX |

Table 24 Hair color codes

| Hair color attribute | Attribute code |

|---|---|

| Unspecified or unknown | XXX |

| Bald | BAL |

| Black | BLK |

| Blonde or Strawberry | BLN |

| Brown | BRO |

| Gray or Partially Gray | GRY |

| Red or Aubum | RED |

| Sandy | SDY |

| White | WHI |

| Blue | BLU |

| Green | GRN |

| Orange | ONG |

| Pink | PNK |

| Purple | PLE |

In addition to the federal mandate, different states have also established their own policies, procedures and guidelines when it comes to data collection of incarcerated individuals, some of which may ask for further details.

In California, for instance, the California Department of Justice’s data collection and reporting responsibility code, PC13102, Clause B, states that under the code, the department has the responsibility to collect and report statistics showing the “personal and social characteristics of criminals and delinquents.”

Further, PC 13020 states: “It shall be the duty of every city marshal, chief of police, railroad and steamship police, sheriff, coroner, district attorney, city attorney and city prosecutor having criminal jurisdiction, probation officer, county board of parole commissioners, work furlough administrator, the Department of Justice, Health and Welfare Agency, Department of Corrections, Department of Youth Authority, Youthful Offender Parole Board, Board of Prison Terms, State Department of Health, Department of Benefit Payments, State Fire Marshal, Liquor Control Administrator, constituent agencies of the State Department of Investment, and every other person or agency dealing with crimes or criminals or with delinquency or delinquents, when requested by the Attorney General:

(a) To install and maintain records needed for the correct reporting of statistical data required by him or her.

(b) To report statistical data to the department at those times and in the manner that the Attorney General prescribes.

(c) To give to the Attorney General, or his or her accredited agent, access to statistical data for the purpose of carrying out this title.

IMPORTANT: Please take note that despite this, Biometrica does not allow even law enforcement agencies to upload juvenile or delinquent data into the NatCrime database (UMbRA). We allow no juvenile data in our system at this point and do not see this changing in the foreseeable future.

Do also see the FBI UCR here.

What is UMbRA modeled on?

Biometrica’s NatCrim database is modeled on the National Crime Information Center (NCIC), which is a computerized index of criminal justice information, including criminal record history information, fugitives, stolen properties, missing persons. However, unlike the NCIC, we currently only maintain law enforcement-sourced records relating to criminal history, i.e. like arrest/conviction/sex offender/warrant list records. UMbRA does not carry records of missing persons or any records not sourced from law enforcement.

As with NCIC records, records in UMbRA are protected from unauthorized access through administrative, physical, and technical safeguards. These safeguards include restricting access to those with a need to know to perform official duties; and using encrypting data communications to create an audit trail that maintains a legally viable digital chain of custody.

Please note, we do not touch or manipulate LEA (Law Enforcement Agency) data in any way, except for collecting and amalgamating the data at the back end. As all of the data is sourced 100% from law enforcement public record, we don’t touch it in any way in order to avoid compromising data integrity, which is why you’ll see some inconsistencies in how the data is entered from state to state or even county to county.

What do you mean by “inconsistencies”?

This means we don’t correct inputting errors either. For instance, we found a record of a man arrested by the Maricopa Co. Sheriff’s Office in Arizona in October 2017. His details included his being entered as having “blue” hair, when his image showed him as having strawberry blond hair. We didn’t change that, as that is what was entered by law enforcement. We don’t ever manipulate that data.

UMbRA & eMotive FAQ

What is UMbRA?

UMbRA is Biometrica’s NatCrim (National Criminal) database, currently at almost 21 million records and growing. This database keeps expanding as more individuals are arrested and/or convicted, and more counties are brought into the system. Data is pulled every hour into UMbRA from every jurisdiction in the system, but whether new data from a particular jurisdiction is reflected in the system or not depends on whether the law enforcement body concerned has updated their own database and has made those records public as yet.Typically, data from a jurisdiction (county/city/regional authority) is updated withinan hour to 24 hours of an arrest wherever possible, so, it is as real-time as possible.

UMbRA also allows subscribers to run manual background checks on individuals by text (name, other demographic details) or face (uploading a photograph).

So, UMbRA isn’t an automated background check?

No, it is a real-time database of arrests, which also provides subscribers the ability to run a manual background check in under 20 seconds. If you, as a CRA or employer, would like to be automatically notified if an employee has potentially been arrested, you’d have to subscribe to eMotive.

What is eMotive?

eMotiveis Biometrica’send-to-end encrypted, next generation, multi-jurisdictional 24×7 continuous background checking software. It gives an organization the ability to be notified in near real-time, through an encrypted alert to authorized company personnel, that an individual matching the profile of one of its employees/contractors/volunteers/vendors has potentially been arrested. This typically happens within an hour to 24 hours of an individual’s arrest and within minutes of that arrest being updated in law enforcement databases. Data in eMotive runs against UMbRA on a 24×7 basis, but eMotive data is only available to authorized personnel within an organization. UMbRA data is available to all subscribers.

Biometrica is FCRA compliant and an associate member of the Professional Backgrounders Screening Association (PBSA), formerly known as the National Association of Professional Background Screeners (NAPBS).

eMotive Video (From Biometrica, animated version — how it works)

https://biometrica.wistia.com/medias/m2a6qnlzkq

How do I get a subscription to eMotive?

Contact us at here, using the form at the bottom of the page, and we will get in touch with you about implementing eMotive.

How do I get started once I have a subscription?

See our Getting Started page and documentation for eMotive here.

Could you elaborate on how eMotive works?

• You will, with permission from your employees or contractors, upload their images and relevant demographic information to that private database. This private database is visible to no one but your organization’s HR or compliance personnel. An eMotive account is not turned on till an organization certifies in writing to Biometrica that it has informed its staffers about their being continuously monitored for criminality and has their permission to do so.

• Our algorithms will then run continuous biometric comparisons against the larger UMbRA NatCrime database in the background.

• These comparisons are being run to let your HR or Security person know, in near real-time, when someone that the algorithm thinks is a potential match to your employee, based on biometric parameters, is arrested somewhere in the United States.

• How it would work is that there would be comparisons run against UMbRA on a constant basis. UMbRA data from each jurisdiction is updated between every hour to 24 hours, depending on a law enforcement jurisdiction or more specifically, when law enforcement within that jurisdiction updates its data, and how often it makes that updated data available.

• So, if someone called John Smith is arrested and you have a John Smith on your list, eMotive at the backend would automatically run a search against search parameters to see if the John Smith arrested is a possible match to the John Smith on your record. Name, Facial Recognition and other parameters would be matched.

• If those are a potential match in the check against UMbRA, the eMotive system would send your authorized personnel an encrypted alert in the form of a uniquely targeted email notification, a link attached to an email asking them to log into eMotive.

• Once your HR person logs into the system and is authenticated, it is then up to that HR person to look at the information and make a final determination as to whether there is a match, and if there is, what next steps need to be taken, if any.

What is the difference between eMotive and other background checking systems?

The difference between eMotive and most other background checking systems comes down to this:

* It is a multi-jurisdictional 24×7 criminal background check, i.e. continuous monitoring, as opposed to an annual or single point-in-time background check.

* You are updated as soon as law enforcement updates data, about a potential match to an employee, and provided information on that match. You, as the CRA or employer, can then make the final determination on that match.

* It searches against both text and facial recognition parameters to prevent false positives.

* All notifications are through encrypted alerts — to preserve and protect PII, create an audit trail, and maintain a legally viable digital chain of custody.

* Comparisons are run against a 100% law-enforcement sourced multi-jurisdictional NatCrim database.

Why is continuous monitoring important, as opposed to a single point in time background check?

For obvious reasons, if you work with children, vulnerable adults, or are in any public facing job. Additionally, because it’s important for any organization to keep their employees safe, even from other employees when necessary, or know when any employee potentially needs help of any kind, in order to prevent workplace violence or an insider threat. Finally, because of Presidential Policy Directive 21 (PPD-21) on Critical Infrastructure and Resilience in 2013, which established national policy on critical infrastructure security and resilience and declared it a “shared responsibility” among the Federal, state, local, tribal, and territorial (SLTT) entities, and public and private owners and operators of critical infrastructure.

PPD-21 identified 16 critical sectors where it mandated self-reporting requirements for arrests when it came to any of these 16, for a variety of reasons, from cybersecurity to physical security to public safety. Basically, this was to maintain the development of situational awareness capability, and constantly reevaluate threat and risk assessments.

What are the 16 critical infrastructure sectors?

• Chemicals

• Commercial Facilities

• Communications

• Critical Manufacturing

• Dams

• Defense Industrial Base

• Emergency Services

• Energy

• Financial Services

• Food & Agriculture

• Government Facilities

• Healthcare & Public Health

• Information Technology

• Nuclear Reactors, Materials & Waste

• Transportation Systems

• Water & Wastewater Systems

For more on each sector, see DHS CISA here: https://www.cisa.gov/critical-infrastructure-sectors

Also see FEMA’s Protection FIOP (Federal Interagency Operational Plan).

Read more here:

https://blog.midches.com/blog/16-critical-infrastructure-sectors

Having information handy makes sense. What an HR or compliance person does with that information is their call, based on organizational policy and appropriate state and federal law and guidance. But information helps put up red flags, maintain a legally viable audit trail, bring down liability costs, bring down the overall costs of insurance, helps organizations maintain compliance and licensing norms, and most importantly, gives them a clear path to protecting themselves, their employees, and the people or public they serve.

Why do we talk about UMbRA when we mention eMotive?

* UMbRA is the overall criminal database and search engine. eMotive is the 24×7 monitoring ecosystem which will, to put it simply, allow you, as an organization, to create your own private database of your employees or contractors or vendors, a database that will sit “below” UMbRA.

* You will, with permission from your employees, upload their images and relevant demographic information to that private database [this private database is visible to no one but your organization’s HR or specific compliance or security personnel].

* Our algorithms will then run continuous biometric comparisons against the larger UMbRA database in the background.

What purpose will these continuous comparisons serve?

To let your HR or security person know, in near real-time, when someone that the algorithm thinks is a potential match to your employee, based on biometric parameters, is arrested somewhere in the United States.

Again, what does eMotive do?

It is a product that provides an organization with the ability to enter all its employees into a database, and be notified in near real-time, through an encrypted alert, when someone matching the profile of one of its employees has potentially been arrested.

This would allow any company that has a requirement to do an annual background check (typically costing between $50-$250 or more per employee for a single point in time check) or with self-reporting requirements in the case of an arrest, to cut costs, improve notification systems, share information to protect their human and other assets and put in place practical systems to prevent insider threats and reputational and other damage, while essentially doing a 24×7 criminal background check. eMotive allows continuous monitoring, which would be a dramatic improvement over a single annual background check or a point-in-time check.

Could you elaborate on the continuous monitoring aspect?

This is a new product and is specifically focused on continuous monitoring or a continuous background check for workplace and public safety and compliance reasons.

• It would work by you uploading a list of your employees (or any other list of people), with their permission, into a separate silo that sits beneath UMbRA’s arrest database.

• Because that siloed data contains PII or personally identifiable information, it would not be accessible to other UMbRA users, and even within your organization it would only be available to authorized personnel from the organization. It would not be accessible by Biometrica staffers.

• We have security in place to ensure that only you/your authorized personnel have access to the data in your silo.

• How it would work is that there would be comparisons run against UMbRA on a constant basis. UMbRA data is updated between every hour to 24 hours, depending on a law enforcement jurisdiction or more specifically, when law enforcement within that jurisdiction updates its data, and how often it makes that updated data available.

• So, if someone called John Smith is arrested and you have a John Smith on your list, eMotive at the backend would automatically run a search against search parameters to see if the John Smith arrested is a possible match to the John Smith on your record. Name, Facial Recognition etc. would be matched.

• If all of those are a potential match in the check against UMbRA, the eMotive system would send your authorized personnel an encrypted alert, asking him or her to log into eMotive because they have a notification.

• Once your HR person logs into the system and is authenticated, it is then up to that HR person to look at the information and make a final determination as to whether there is a match.

To expand on this, every employee on your list in eMotive, will be run against every arrest that comes into UMbRA (the NatCrime database) on a constant basis. If you have 50,0000 employees on a list, and 10,000 arrests come in today, all 50,000 employees will be run against all 10,000 arrests coming in today. This happens every day.

Employee data is PII. How do you protect PII?

As employee data is Personally Identifiable Information or PII, we have to ensure that employee data and access to employee data is protected. Every employee in an organization mayor may not have an arrest record, and even if they do, their employee details should still be protected and access to that record still needs to be encrypted and monitored. Biometricais fully FCRA compliant. Every part of eMotive is end-to-end encrypted, and data is shared and notifications provided in a process similar to the movement of HIPAA data.

A company authorized person receives an email notification (without the employee name) as an alert. What we use is a Uniquely Targeted Email Notification, a notification that is unique to that particular alert. It is a notification that is produced in relation to a specific alert and is transmitted to a curated list of recipients — that may or may not be a single recipient — that has explicitly opted in at a prior time to receive that notification. It can be tracked and audited to reflect when it was transmitted, if it was opened,when it was read, to what action was taken thereafter.

Every single action or event is tracked, to maintain chain of custody and create an immutable digital audit trail, for legal and judicial purposes. For example,if an employee on your list, for instance, a driver, is arrested for a DUI on a Friday night, and gets out Saturday afternoon. Your HR person receives a notification asking them to log into eMotive and see information on a potential match to an arrested individual, but they do not check it, as it’s a weekend. Suppose that employee gets inebriatedagain anddrives a work truck into something Monday morning. You can actually see the audit trail for when the notification alert was received, whether it was even acknowledged, and if it was acknowledged, whether anything was done about that acknowledgement (at least in the system). There’s a process in place, one that can’t be manipulated.

What happens if someone is arrested and not convicted?

Our data is updated when law enforcement updates data. Please note:

1. Your arrest record and your prosecution record effectively live in two separate baskets. So you might be booked, released, charges dropped, found not guilty, but that arrest is a matter of record until the prosecutorial body updates the law enforcement agency with the status, and the law enforcement agency, in turn, takes the trouble to update its own record to reflect that status.

2. It’s time-consuming and complicated, even in cases that were dismissed, for a record to be sealed or expunged or annulled or have what’s called “records restricted” (Georgia), a “Declaration of Factual Innocence” (California), such that an individual can lawfully deny the arrest — it depends on the state, the type of offense (violent offenders and sexual offenders are generally excluded), the outcome of the case, the age of the defendant, and procedures vary very widely.

For more, take a look at this excellent site, The Restoration of Rights Project.

From our perspective, if the law enforcement body updates that record and removes it, we could. If someone lets us know, we could. We already have a system in place for consumer rights or disputes here.

https://www.biometrica.comrecord-request-procedures/

Do you collect juvenile data, i.e. records for offenders that are under 18?

No. We have no juvenile records and have no plans to collect juvenile arrest or conviction data.

Can an employer ask about expunged or erased records?

Toweigh the scales fairly between an employer’s “need to know” for the protection of their organization, other employees, and the people who interact with them, against an employee or prospective employee’s right to privacy and opportunity for equal employment, a number of federal and state laws regulate both the kind of information an employer or prospective employer might obtain about a job applicant or employee, and what they might actually look at. The extent of the check also depends on the role in question:Whether, for instance,it is a security or safety-sensitive position, whether there is interaction with, say, children or vulnerable adults, and if that role also has to meet federal background check requirements because it comes under an industry or sector classified as critical infrastructure. Before conducting background investigations, employers should be fully aware of the requirements under applicable law and ensure that their pre and post-employment screening practices are in compliance.

Depending on the job in question, and the state, expunged records sometimes have to be made available during background checks. In Arizona, for instance, from April 2019 onward, all non-certified teachers must disclose whether they have had criminal offenses expunged from their records.In Virginia, however, employers are prohibited from requiring an applicant for employment to disclose information concerning any arrest or criminal charge against him or her that has been expunged.

Who makes the determination on whether Employee A is a match to Arrested Individual Mr. A?

It is always the employee authorized by the company. All our algorithms do is run continuous matches against information sourcedfrom law enforcement data and present that information to an organization’s authorized personnel. We cannot directly inform the individual concerned because the determination on whether it is the individual concerned or not is not made by us under any circumstance. It is made always by the employer (HR) after that HR person or administrator, once notified as having an alert, has signed into eMotive, clicked on the alert and made a determination on whether arrested Individual A is Employee A or not.

What do you do to explain this to employers and employees using your data?

We always recommend that as part of the onboarding process, over and above what is included in certifications from employer/employees, an organization does the following:

* Have a virtual demo of eMotive, showing what happens with a possible arrest. Emphasize that this situation only happens in case of an arrest.

* Include it in the employee handbook

* Show that in the case of an HR person making a final determination of a match, Individual A should receive a notification saying there is a public record that someone with their likeness may have been arrested, and that they may want to check if this is the person concerned.

(Note: Despite systemic inconsistencies, it’s unlikely that a wrong person will get a notification: You’re going to have to get a number of things exactly the same and that will be unusual). A false positive is rare.

* Double check with the law enforcement jurisdiction involved and follow up with the prosecutorial office involved on the case status. The arrest details are part of the case file.

Do have a look at this graphic below (these are DOJ stats).

What is a Uniquely Targeted Email Notification?

A uniquely targeted notificationis a notification that is unique to that particular alert. It is a notification that is produced in relation to a specific alert and is transmitted to a curated list of recipients — that may or may not be a single recipient — that has explicitly opted in at a prior time to receive that notification. It can be tracked and audited to reflect when it was transmitted and read.

What is the difference between Arrest and Conviction Data?

Arrest And Conviction Data Do Not Come From The Same Source

• Law Enforcement Agencies (LEA) of different stripes at the local level (city/county/municipal authority) update arrest data, which is almost entirely digitized across the U.S. with text and facial recognition data feeds available for a large number of arrested individuals.

• Conviction data comes from the courts, and lives in the prosecutorial basket. It is, for the most, textual data, not connected to facial recognition and in most cases, also not uniformly/comprehensively digitized. You often have to go in person to a courthouse and ask for a file on a particular case, as that case information may not be digitized.

Note: Law Enforcement may or may not update an arrest in a system to reflect the status of a case through the courts— this varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction and is largely dependent on the availability of time and manpower in that jurisdiction.

How often is data updated?

Datais updated on a 1-24-hour update cycle per jurisdiction basis with respect to records, but please note this is only with reference to arrest records.The 1 hour to 24-hour update cycle timeline is accurate only with respect to the actual arrest itself, because that is the typical time-frame law enforcement jurisdictions take to update their public arrest databases on a daily basis. Some jurisdictions do it hourly, some do it every 24 hours, some do it every eight hours. UMbRA, our NatCrim database, updates as they do.

Similarly, when a LEA updates an arrest record status to reflect a case’s progression or adjudication in court, for instance, that progression or adjudication will be reflected in UMbRA because it picks up every update made by law enforcement — when they make it. eMotive runs against UMbRA. This progression as the case is adjudicated in the system, is what was referenced to in that statement about following someone as they go “through the system.”

From our perspective, if the law enforcement body updates it, we will update it. If someone lets us know about an update with a formal court order, we could update it. We already have a system in place for consumer rights, mentioned above. At every step of the way in the eMotive system, the HR person also has the ability to print notifications for the employee.

Our arrest database. That number, as mentioned above, is constantly changing as we add more counties and more people are arrested every day. Data is updated every hour to 24 hours from each jurisdiction wherever possible, so it’s pretty current once a county has come into our intake pipeline, allowing us to follow someone as they go through the system, depending on when the law enforcement body concerned updates its records. There is no other private organization that includes immigration arrest records, USPS, Secret Service or FBI data, along with a number of other federal arrest records, given that federal arrest records are not open to the public.

For most U.S. jurisdictions, existing background checks are reporting, for the most, not on arrests but on convictions or court cases. It can take between 24 hours to 6 weeks before a court case might be entered into a system and years before it is adjudicated in some cases. In addition, the courts only track people by Court ID number and textual data; the issue with this is that you end up with too many false positives on names (for instance, “John Smith”) and the information gets to you way too late. The problem with this is that the obligation in many industries/sectors/jobs is to self-report if arrested and not just when convicted. It is, therefore, not just a risk to the employee concerned, it is a potential reputational, financial, and legal risk to the company or organization that is employing that employee, contractor or vendor, if not worse. Continuous monitoring gives organizations the ability to put their people first, and their people’s lives first, while protecting themselves.

Do you update arrest status or progression through the system also hourly/daily?

The 1 hour to 24-hour update cycle timeline is accurate only with respect to the actual arrest itself, because that is the typical time-frame law enforcement jurisdictions take to update their public arrest databases on a daily basis. Some jurisdictions do it hourly, some do it every 24 hours, some do it every eight hours. UMbRA, our arrest database, updates as they do.

Similarly, when a LEA updates an arrest record status to reflect a case’s progression or adjudication in court, for instance, that progression or adjudication will be reflected in UMbRA because it picks up every update made by law enforcement — when they make it. This progression as the case is adjudicated in the system, is what was referenced to in that statement about following someone as they go “through the system.”

From our perspective, if the law enforcement body updates it, we will update it. If someone lets us know about an update with a formal court order, we could update it. We already have a system in place for consumer rights. At every step of the way in the eMotive system, the HR person also has the ability to print notifications for the employee.

What is recommendedfor organizations as part of the onboarding process for eMotive?

* Have a virtual demo of eMotive, showing what happens with a possible arrest.

* Include details in the employee handbook

* Emphasize that in the case of an HR person making a final determination of an employee match to an arrest record, the Employee should receive a notification letting them know that there is a public record that someone with their likeness may have been arrested, and they may want to request a copy of that information.

* Double check with the law enforcement jurisdiction involved and follow up with the prosecutorial office involved on the case status of a record.

How does Facial Recognition work exactly and is it accurate?

When it comes to matching two faces, the accuracy of facial recognition depends on several things includingthe age of the subject in the photo, the angle, the lighting, the cameras being used. Then you look at the size of the database you’re comparing your photo against: Is it a 1:1 comparison or a 1:1,000,000 or 1: N

If you are doing a 1:1 match, say a picture of the person standing in front of you and his driver’s license, or the photo inside the chip in his passport, this kind of match recognition and confidence rating will be fairly high: over 90%, depending on the time between the initial photo and the current one. If you are doing a 1: Many or 1: N search, the accuracy rate drops but is still a key factor in improving your match ability. This also depends on how many photos of an individual the gallery or database has and over what time period.

Computers look at faces differently from humans. Computers look at faces as points in a facial template; humans look at faces as a whole. If, in the case of a sex offender, the system has a photo of an individual every year (for the worst sex offenders this is a requirement of Megan’s Law), and the system is presented with a photo or video of a person on that list, it is likely the person would be found within the first 10 results. You’re still going to need the human looking at the matches presented by the algorithm to give you the best option. But our system runs a search against millions in the UMbRA database in mere seconds. A human cannot do that. But a human can look at the two profiles an algorithm has matched from millions and make a final determination on whether they are actually a match.

Just to be very clear from a technical standpoint on how Facial Recognition works. We run a mathematical formula that runs numbers against numbers. We run an algorithm that creates a unique hash template that matches up against another unique hash template, which then generates a confidence rating. It’s a misnomer really that FR actually compares faces. We say that for easy understanding, but in the actual systemic process, in reality, it’s not a face-to-face comparison, it’s a numbers-to-numbers comparison from a machine intelligence perspective, which is why we present it to a human to do the final adjudication on eMotive. We hope this helps in understanding it all.

What is the search scope of your system?

The system runs a search against everyone in the database when comparing employees in eMotive datasets for potential matches. At this point, that figure is in the range of 21 million, by the end of Q2 2023, it is likely to be substantially higher.

What information would an employer upload?

• The data the employer is required to upload, at the moment, includes: First Name, Last Name, Date of Birth, Home Address and Photograph.

• The match is currently algorithmically run against the name and photograph with a final determination to be made by an administrator appointed by the employer.

• No Biometrica employee or contractor is involved in this process at any stage.

• An employer has these optional data fields they can also upload: Prefix, Middle Name, Suffix, Race, Gender, Eye Color, Hair Color, Notes and Work Address.

• The additional section called “Notes” is for the employer’s administrative convenience.

• We added the section for home and work mailing address so HR could automatically send out the requisite notices when they make an adverse determination.

Note: Law enforcement jurisdictions vary vastly on what data they make available when it comes to each of these fields. For instance, almost all indicate gender, some indicate race, some say “unknown” for race but there’s no standardization of fields when it comes to race. Some put in eye color and hair color, but again, there is little standardization.

Who is the “determining employee?”

This really depends on a company’s set-up. It could be an HR administrator, a legal team member, a security head, or a compliance officer. Typically, in most companies, personnel matters come under HR. This is for the sake of writing. Each company could set it up as they please. In some places, we’ve used the word administrator interchangeably.

What items does eMotive match against?

Algorithmically, the system first matches Name and Facial Recognition against law enforcement databases and then presents possible matches to the human for determination if a possible match is identified against those two parameters. The system then present the employer administrator with all the data that the jurisdictional county makes available to the system (which differs in the case of each county): It could be Age, Race, Gender, Height, Eye Color in one case, it could be Age, Race, Gender, in another, or Age, Gender, Height, Eye Color, Hair Color in yet another, to make a final determination. It depends on what data is available. Again, do note that the final determination of a match is made by the employer. No Biometrica employee is involved in any way at any stage in this process.

Does Biometrica have any say in the records update process?

No, when a law enforcement body updates a record, UMbRA automatically pulls in that record in real time. It’s systemic and automatic — we cannot manually override these updates, unless we dismantle the bot or the entire system for that particular county, so it will ALWAYS reflect the newest available LEA arrest record on an individual. You will be provided with available records for that individual in the system if you’re looking at possible adverse action cases.

Casino FAQ

This FAQ is intended for informational purposes only. This information has been aggregated and compiled in document form for the understanding and convenience of customers, clients and partners of Biometrica Systems, Inc. All references have been sourced from public record, including but not limited to court, FTC and FCC documents, and all sources have been both linked to and noted in the footnotes on every page. Please do not copy to or share with unauthorized users or systems, in whole or in part, without permission. This is not a substitute and not intended to be a substitute for legal advice or information.

This is merely intended as a handy guide to best practices for casino customers, and provide a background on topics like Casino SARs, PII, KYC, regulatory, compliance and licensing requirements, maintaining transparency, AML and asset protection measures. Parts of this FAQ have been shared over the years with casinos in the form of white papers or training manuals. Do also note that this FAQ will be updated from time to time, both in terms of scope of content and in terms of changes in the content itself, because of compliance and legal cases, events and other incidents. Please write to marketingbiometrica.com if you want more information on source, or would like to provide any corrections or suggestions.

In its most basic form, Personal/Personally Identifiable Information or PII can be defined as information that provides access, directly or indirectly, to a unique individual’s identity. Generally, when companies are reminded about protecting consumers or clients’ PII so as to not cause identity theft or misuse, or expose an individual to financial harm, embarrassment, discrimination, or physical or mental trauma, the reference is typically to sensitive PII (sometimes called SPI or Sensitive Personal Information). This is usually information on an individual’s first name or first initial and last name, in combination with one or more of other data elements, including but not limited to the following:

• A Social Security number

• A driver’s license or state-issued ID card, or a passport

• A home address, phone number or personal cell phone number

• An individual account number, a credit or debit card number

• A biometric record, like a photographic representation or image

What isn’t classified as personal information is data that is legally or lawfully available to the general public, from federal, state, tribal or local government records, or has been widely distributed by what are reasonably considered legitimate media organizations.

This FAQ also provides information on the concept of personally identifiable information, the transmission of sensitive personal information data through different means, and details why communication systems like email are inherently insecure and could leave you and your organization open to civil and criminal penalties — if PII is transmitted unencrypted, shared, stored or read on insecure devices — provides clarity on the statutes governing the viewing and sharing of consumer PII for businesses, including casinos, explains the compliance requirements mandated by law, and provides examples of non-compliance and some of the penalties imposed for non-compliance and security breaches under state and federal laws, including the laws of Nevada.

The Prohibitive Cost Of A Security Breach

The 2019 14th annual study on the cost of data breaches, by IBM and the Ponemon Institute, put the average total cost of a single instance of a data breachat almost $4 million ($3.92M) globally, with each stolen record costing, on average, $150 globally. The study estimates that the average size of a data breach, i.e. the number of records that have their data compromised in a single instance of a breach is 25,575.

In the United States — by far the most expensive country in the world to have a data breach in — those expense numbers are dramatically different. The average total cost of a single instance of a data breach in the U.S. is $8.19 million ($7.91M in 2018), with the cost per lost record standing at $242. The time to identify and contain a data breach in the U.S. is 245 days, as opposed to 279 globally. This does not include the long tail costs of a data breach, which, as the study says, and companies have experienced, can last for years, in monetary, legal and reputational damages.

According to the study, about a third of data breach costs occurred more than one year after a data breach incident. While an average of 67% of breach costs came in the first year, 22% accrued in the second post-breach year, and 11% in the third. But in highly regulated environments like the finance industry — important to note as most casinos are NBFIs or Nonbank Financial Institutions (see more on this below) —the long-tail costs of a breach were higher in years two and three. Organizations in a high data protection regulatory environment saw 53% of breach costs in the first year, 32% in year two, and 16% in the third year.