Ninety Years On, The FBI Officially Sends SRS Into Sunset

It’s been in the works for five years-going-on-35, but it’s all finally official. On Jan. 1, 2021, the National Incident-Based Reporting Program officially replaced the Summary Reporting System as the UCR’s data standard. We take a look at the history of the Uniform Crime Reporting Program, its reporting components, and at why the system needed change.

By Kadambari Wade

Here’s the not-so-short story. Well before the dawn of any kind of digital data, the U.S. Bureau of Investigation (then the BOI, now the FBI) figured out a paper-based system that would provide a picture of crime in the United States. The Bureau’s Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Program was established about 90 years ago, and it began amalgamating crime data contributed by participating law enforcement agencies through what was called the Summary Reporting System (SRS).

While the SRS adapted to the electronic age as best as it could, basic indexing issues and an inflexible, archaic structure made it incompatible with the advent of a data-driven modern age. Here’s an example of that inflexibility, according to a 2017 FBI report. “To simplify the reporting and tabulation of numbers, SRS features a hierarchy rule that ranks the crimes in order of severity and accepts the report of only the most severe crime within a criminal incident. For example, if a criminal incident includes a robbery and a murder, the hierarchy rule dictates that a law enforcement agency reports only the murder.” Essentially, for crime data reporting purposes, that robbery just didn’t exist. Change was obviously needed.

The process of change began 35 years ago but we’ll come to that in a bit. Five years ago, on Dec. 2, 2015, in an effort to upgrade and update the country’s statistics on crime — which form the basis for policy — the FBI’s Criminal Justice Information Services (CJIS) Advisory Policy Board passed a recommendation that all federal, state, county, local, and tribal law enforcement agencies move from SRS to a much more comprehensive system, called the National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS), by 2021.

On Feb. 9, 2016, then FBI Director James Comey signed off on this recommendation, saying, “By transitioning to a NIBRS-only data collection over the next five years, the FBI will have faster access to more robust data that is necessary to show how safe our communities are and to help law enforcement officials and municipal leaders better allocate resources to prevent and combat crime in their jurisdictions.”

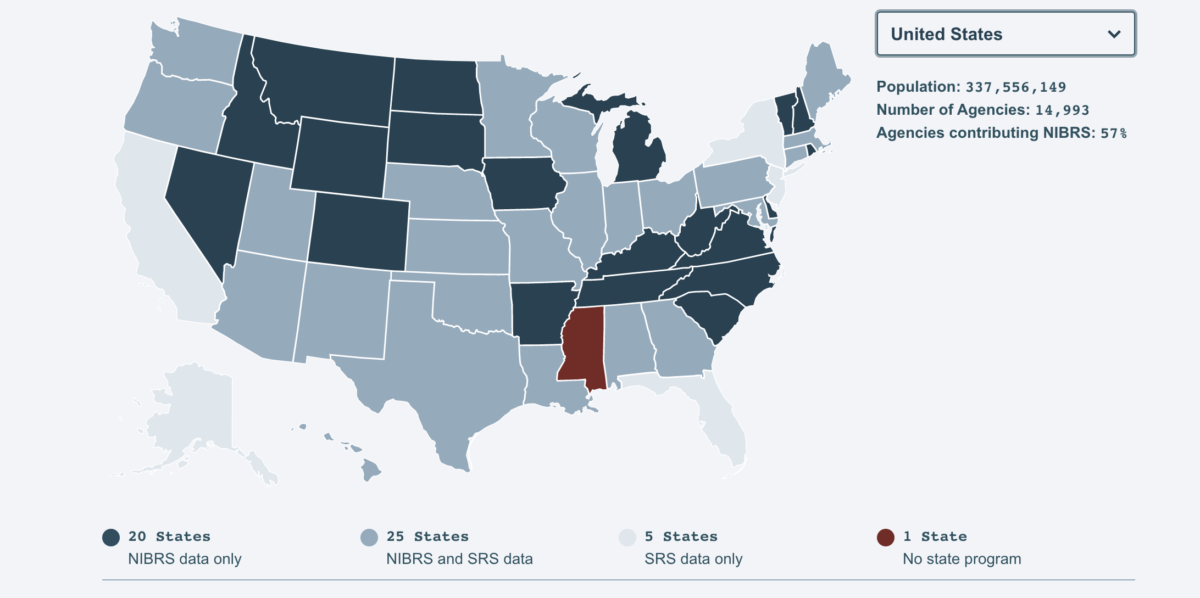

Despite some worry over whether keeping that deadline for law enforcement agencies made sense against the backdrop of the coronavirus pandemic, on Jan. 1 this year, the NIBRS (pronounced “ni’-bers”) officially became the standard national crime data collection program. But that doesn’t mean it’s all done and dusted. Contributions by law enforcement agencies to federal crime collection programs in the United States are recommended but not mandated. For instance, the 2019 FBI arrest statistics for the U.S. are based on data received from just 11,788 law enforcement agencies that submitted 12 months of arrest data out of the 18,671 total number of agencies operating in the U.S for that year. Basically, nearly 37% of agencies opted not to submit arrest data to the FBI.

As of Oct. 31, 2020, 43 states were classified as being NIBRS-certified, i.e., these states had records management systems (RMS) that met the FBI’s technical and other requirements for collecting and sending across crime data. At that point in October, 8,742 law enforcement agencies representing 48.9% of the U.S. population were reporting NIBRS data to the UCR Program. By the end of this year, the FBI, perhaps optimistically, anticipates that 75% of law enforcement agencies would have moved over to NIBRS. These agencies are in areas that collectively hold more than 80% of the U.S. population.

What was the Summary Reporting System?

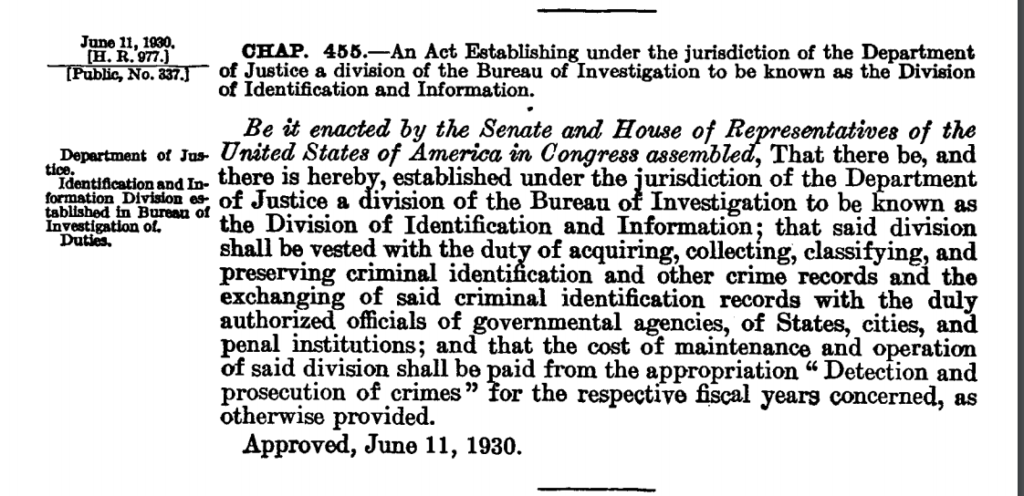

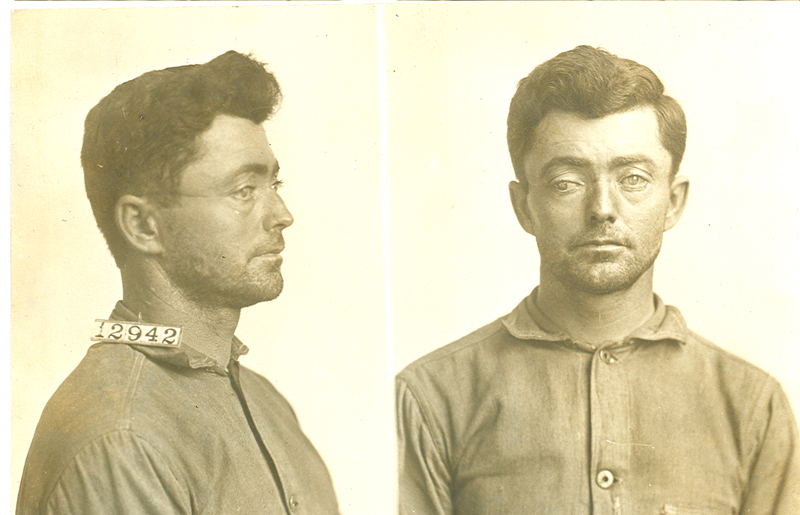

Image source: United States Congressional Record

It was an original system devised by U.S. chiefs of police almost a century ago to track crime statistics reported by law enforcement. Here is a year 2,000 piece from the CJIS Newsletter (Volume 4, No. 1), which explains it quite precisely. “… The information to be reported [to SRS] is based on a hierarchy system, i.e., when a criminal incident occurs, police report the most serious offense identified within the incident according to the crime hierarchy established by the UCR Program — murder being the most serious, followed by rape, robbery, aggravated assault, burglary, larceny, and motor vehicle theft. In multiple-offense incidents, e.g., a victim is robbed and then murdered, the lesser offense (robbery) is disregarded in the national crime count. (The exception is arson, which is always reported.)”

Through the Summary system, the UCR Program collected crime details about the victim, the offender, and the circumstance only in the case of a homicide. But it was limited in scope. It didn’t collect details on the kind of weapon used in the commission of a crime, unless that crime was specifically one of murder, robbery, or aggravated assault. Importantly, if a weapon was used during a rape, the details on that weapon were not recorded, and critically, rapes were reported only for female victims. Seriously.

For decades, “forcible rape” had been defined by the UCR SRS as “the carnal knowledge of a female, forcibly and against her will.” That definition remained basically unchanged between 1927 and 2012. According to a Department of Justice news release on the subject in 2012, till that point of redefinition, it only included “forcible male penile penetration of a female vagina.” There was no mention of male rape. The new definition of rape, announced on Jan. 6, 2012, was this: “The penetration, no matter how slight, of the vagina or anus with any body part or object, or oral penetration by a sex organ of another person, without the consent of the victim.”

While the Bureau’s change, according to RAINN, the country’s largest anti-sexual violence organization, did not affect any criminal laws, it adjusted the definition for statistical purposes, so that crimes under existing state laws could “now be acknowledged, and counted by, the federal government.” All in all, it really did make sense to update not just the definition of rape, but the system as a whole.

Enter the NIBRS. What exactly is this?

The NIBRS, like its predecessor SRS, is a component of the FBI’s UCR Program and is focused on crime statistics in the United States. The NIBRS, curiously perhaps, isn’t particularly new. It was created in the 1980s. But the process of moving the U.S.’s more than 18,000 law enforcement agencies to an IBR (Incident-Based Reporting) system has been a long and often, fraught journey — one that is not yet done.

The NIBRS first made its appearance in 1985 with the publication of an almost 350-page joint report by the FBI and the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS), called the “Blueprint for the Future of the Uniform Crime Reporting Program.” The culmination of a three-year-study, the report looked at “bringing crime statistics into the electronic era.” The blueprint called for the development of a more robust, technologically adept crime statistics reporting system, one that would gather more comprehensive data than the SRS. That system became the NIBRS.

Why did the system need change? According to the FBI, they implemented the NIBRS to “improve the overall quality of crime data reported by law enforcement.”

The 1985 blueprint stated, “Many larger departments are computerized, with the potential to maintain a wealth of detail on offenses, arrests, police activity, and manpower. Some state programs have begun to collect data additional to UCR information, including detailed breakdowns of offense types, victim descriptions, and, in some cases, individual case record data and disposition and sentencing information. Other databases have been constructed based on victimization surveys and on the compilation of offender-based records that track cases through the criminal justice system. This development is unquestionably uneven.”

The FBI actually began collecting crime data for the NIBRS 30 years ago, in 1991. Then, inexplicably, for the two decades that followed, they made that NIBRS data available by request on data files but did not publish it till 2011, when it reported data contributed by 5,880 law enforcement agencies, who comprised approximately 32% of all UCR agencies.

NIBRS captures incident-level details about crime, including multiple offenses within the same incident, in addition to data on victims, known offenders, relationships between victims and offenders, arrestees, and property involved in crimes. Unlike data reported through the SRS — which was a cumulative monthly tally of crimes and counted only one offense per incident — NIBRS takes a deep dive into each incident to provide information about the circumstances and context of crimes, such as location, time of day, and whether the incident was cleared.

A Brief History of the Uniform Crime Reporting Program

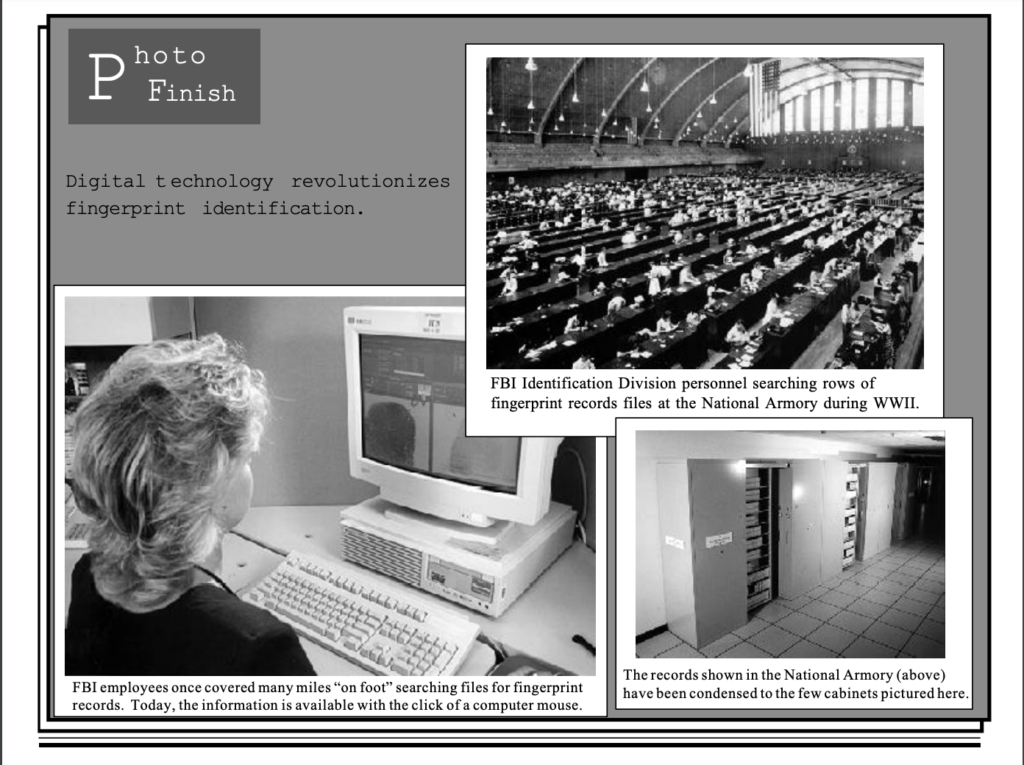

If you’re like us and are crime and data geeks, reading up on the UCR is a fascinating exercise. And there’s reams of matter. It began in the 1920s, when the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP), with an eye on an exponential growth in organized crime against the backdrop of Prohibition, recommended that the United States merge the country’s existing major criminal identification records system in order to make them accessible to all law enforcement. There were two such systems, a federal one at the Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary in Kansas, and the IACP’s records in Chicago. With Congress awarding the funds for the project, in 1924, the Bureau of Investigation (as the FBI was once known) established its Identification Division.

While establishing the division, the top cops at the IACP, working in tandem with the Social Science Research Council (SSRC), also believed there was a need to collect crime statistics nationally. In 1927, the IACP established the Committee on Uniform Crime Records to build a “system for collecting uniform law enforcement statistics for national comparisons.” Headed by Commissioner William P. Rutledge of Detroit, with technical staff funded by the Rockefeller Foundation, the committee developed the system’s reporting rules and forms over the next three years.

As a first step, the committee determined that the number of offenses known to law enforcement, whether or not there was an arrest, would be the most appropriate measure of American criminality. As a next step, it debated and evaluated various crimes on the basis of their seriousness, frequency of occurrence, pervasiveness in all geographic areas of the country, and likelihood of being reported to law enforcement. Based on this, it decided that seven crimes were necessary for comparing crime rates: Aggravated Assault, Burglary, Forcible Rape, Larceny, Motor Vehicle Theft, Murder and Non-Negligent Manslaughter. The eighth Index offense, arson, was added under a Congressional mandate only in 1979.

In 1929, the IACP decided to adopt the system to classify, report, and collect crime statistics, and asked the then Bureau of Investigation to manage the program. And thus, was the Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Program born. It kicked off with the publication, in 1929, of Uniform Crime Reporting, a complete manual for police records and statistics. According to the historical background section in the 2004 FBI UCR Handbook, “During that year, law enforcement agencies in 400 cities from 43 states and the territories of Puerto Rico, Alaska, and Hawaii submitted statistics to the IACP,” which subsequently published the first monthly for what was rather imperialistically titled, “Uniform Crime Reports for the United States and Its Possessions.” That first report contained a lone table: “Number of Offenses Known to the Police: January 1930.”

On June 11, 1930, the Seventy-First Congress formally enacted legislation authorizing Attorney General William Dewitt Mitchell to gather information on criminal activity in the United States through the Division of Identification and Information, under the aegis of the then Bureau of Investigation. The Attorney General, in turn, designated the Bureau to serve as the national clearinghouse for the data collected, and the Bureau took on the task of managing the UCR Program in September 1930.

Image source: Records of the Bureau of Pensions, RG 129.

This image can be found here.

Crime statistics are compiled from UCR data — contributed to by law enforcement agencies across the country — and published annually by the FBI. The UCR Program has four components.

- The SRS (now being retired) and the NIBRS —- which is basically offense and arrest data.

- The Law Enforcement Officers Killed and Assaulted (LEOKA) Program.

- The Hate Crime Statistics Program.

- The Cargo Theft Reporting Program.

The FBI publishes this annual data in Crime in the United States, Law Enforcement Officers Killed and Assaulted, and Hate Crime Statistics series.

NIBRS Offenses

Group A Offenses

Animal Cruelty

Arson

Assault Offenses

- Aggravated Assault

- Simple Assault

- Intimidation

Bribery

Burglary/Breaking & Entering

Counterfeiting/Forgery

Destruction/Damage/Vandalism of Property

Drug/Narcotic Offenses

- Drug/Narcotic Violations

- Drug Equipment Violations

Embezzlement

Extortion/Blackmail

Fraud Offenses

- False Pretenses/Swindle/Confidence Game

- Credit Card/Automated Teller Machine Fraud

- Impersonation

- Welfare Fraud

- Wire Fraud

- Identity Theft

- Hacking/Computer Invasion

Gambling Offenses

- Betting/Wagering

- Operating/Promoting/Assisting Gambling

- Gambling Equipment Violations

- Sports Tampering

Homicide Offenses

- Murder and Nonnegligent Manslaughter

- Negligent Manslaughter

- Justifiable Homicide (Not a Crime)

Human Trafficking Offenses

- Commercial Sex Acts

- Involuntary Servitude

- Kidnapping/Abduction

Larceny/Theft Offenses

- Pocket-picking

- Purse -snatching

- Shoplifting

- Theft From Building

- Theft From Coin-Operated Machine or Device

- Theft From Motor Vehicle

- Theft of Motor Vehicle Parts or Accessories

- All Other Larceny

Motor Vehicle Theft

Pornography/Obscene Material

Prostitution Offenses

- Prostitution

- Assisting or Promoting Prostitution

- Purchasing Prostitution

Robbery

Sex Offenses

- Rape

- Sodomy

- Sexual Assault With An Object

- Fondling

Sex Offenses, Nonforcible

- Incest

- Statutory Rape

Stolen Property Offenses

Weapon Law Violations

Group B Offenses

Bad Checks

Curfew/Loitering/Vagrancy Violations

Disorderly Conduct

Driving Under the Influence

Drunkenness

Family Offenses, Nonviolent

Liquor Law Violations

Peeping Tom

Trespass of Real Property

All Other Offenses