Hate Crimes Against Sikhs In The U.S. — An Overview From 9/11 Until Date

By Deepti Govind

We are just about five months away from the 20th anniversary of the deadly 9/11 terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. Neither the United States, nor the rest of the world, is likely to forget the date, perhaps ever. But there’s another equally important aspect that must not be forgotten about the 9/11 attacks: The spate of revenge killings, or hate crimes, that followed. This holds particularly true in today’s America also, as hate crimes continue against several communities, and in some cases, are on the rise even.

If we look at a two-decade historic timeline, here’s where the chain likely first began with intensity. After the 9/11 attacks in 2001, a man named Frank Roque is said to have told a waiter at Applebee’s that he was going to go out and “shoot some towel heads.” And that: “We should kill their children, too, because they’ll grow up to be like their parents.”

On Sept. 15 2001, an Indian Sikh immigrant, Balbir Singh Sodhi, was out planting crates of flowers in front of the gas station he managed in Mesa, Arizona. Roque found Sodhi planting flowers when he drove up to the station, and shot him five times in the back. He continued his shooting rampage at another gas station, where his bullet narrowly missed a Lebanese American clerk, before going to his own previous home — which had been sold to an Arab family — and firing several more shots.

Sodhi became the first of dozens of people killed in hate crimes against Sikhs and Muslims after 9/11. When police arrested Roque for killing Sodhi the next day, he yelled, “I am a patriot! I stand for America!,” an article by civil rights activist Valarie Kaur in The World says. He was sentenced to death — a sentence that was later reduced to life in prison. He told the court then that voices told him to “kill the devils.” Kaur, who made a film about Sodhi’s murder, wrote that article in 2016. And in that article, Sodhi’s brother Rana Sodhi told Kaur that it felt like nothing had changed, and that the cycle of violence felt endless.

What worries the Sikh community living in the U.S. today, is that not enough seems to have changed in the last two decades since 9/11. On April 16, just last Friday, a mass shooting at a FedEx warehouse at 8951 Mirabel Rd, Indianapolis, left four members of the Sikh community dead. On April 18, officials released names of the eight people who were killed by the 19-year-old gunman in the shooting. The Sikh victims include a mother, a father, and two grandmothers — Amarjit Sekhon, Jaswinder Singh, Amarjeet Kaur Johal and Jasvinder Kaur. All of them, killed suddenly and tragically that night, became yet another senseless American statistic in the spate of mass shootings that have shaken this nation. They’ve also become part of another, less reported tragedy: Of crimes against Sikhs in the United States.

About 90% of workers at the FedEx facility are members of the local Sikh community, police chief Randal Taylor was quoted as saying by the BBC. Gurinder Singh Khalsa, a businessman and leader of the local Sikh community, told Reuters the FedEx center was known for hiring older members of the local Sikh community who did not necessarily speak fluent English. “Given everything our community has experienced in the past–the pattern of violence, bigotry, and backlash we have faced–it is impossible not to feel that same pain and targeting in this moment,” reads a joint statement from eight Indianapolis-area gurdwaras (the term for Sikh houses of worship) published on April 17.

Brandon Scott Hole, the gunman, legally purchased two semiautomatic rifles he used in the attack just a few months after the police seized a shotgun from him, the New York Times reported, citing the chief of the Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department. In March 2020, the police seized a shotgun from Hole after his mother raised concerns about his mental state, records show. He was briefly employed by FedEx last year, and a release on the company’s website says: “Our team continues to work closely with law enforcement. We can confirm that the attack occurred in the parking lot and screening area of the facility where the suspect was previously employed for two months, from August to October 2020.”

FBI agents who interviewed Hole last April found no criminal violation at the time and determined he possessed no “racially motivated violent extremism ideology,” the Reuters report said citing Paul Keenan, special agent in charge of the FBI’s Indianapolis field office. But the attack has renewed fears among American Sikhs, who have over the years been accosted for wearing turbans and attacked in a house of worship, the New York Times added in its report. “The shock wave went through the entire Sikh community. Why would a 19-year-old do that to these innocent people?,” the New York Times report said, citing Kanwal Prakash Singh, who has watched the Indianapolis-area Sikh population grow from a handful of individuals to thousands since he arrived in the late 1960s.

The Sikh Coalition, a civil rights advocacy group based in New York, called for a full investigation into “the possibility of bias as factor” in the FedEx shooting. “No further information about his possible motive has been released at this time, but we fully expect that authorities should and will conduct a full investigation–including the possibility of bias as a factor,” the group said in a press release on April 16, posted on its website. “While we don’t yet know the motive of the shooter, he targeted a facility known to be heavily populated by Sikh employees, and the attack is traumatic for our community as we continue to face senseless violence,” Satjeet Kaur, Sikh Coalition Executive Director said in the statement.

From Temples To Cabs, Sikhs Have Faced Hate Everywhere

Sikhism is the fifth-largest religion in the world, with around 500,000 adherents in the United States, the advocacy group Sikh Coalition says. Many practicing Sikhs are visually distinguishable by their articles of faith, which include the unshorn hair and turban. It is their appearance that has made them a target of racially-motivated crimes. In the aftermath of 9/11, of the many images that probably stayed vividly real in the mind of Americans, was that of Osama Bin Laden — founder of the terror group al-Qaeda. In those images, Bin Laden is shown wearing a turban and sporting a full beard.

“People saw only a turban and a beard,” Rana Sodhi told NPR in 2018. “People yell to us using F-word and asking to ‘Go back to your country.” Sikhs were mistaken to be Muslim because of their turbans and beards in the 9/11, and anti-Muslim sentiment was high in the U.S. following the terror attacks. In September 2013, more than a decade after 9/11, Prabhjot Singh and a friend — also a Sikh man — were walking on 110th Street near Central Park. Singh heard someone yell: “Terrorist, Osama, get him,” and he ran, but not fast enough, according to a CNN report from 2016. A group of boys and young men on bicycles taunted him using racial slurs, which went on to punches and kicks. He lay on the ground, waiting for them to stop, when passers-by intervened. Prabhjot Singh ended up in the hospital with a broken jaw, dislodged teeth, and other gruesome injuries, the report adds.

On a September evening in 2015, a limousine driver, Inderjit Singh Mukker, was picking up food from an Indian grocery store near his home in Darien, Illinois. When he stopped at a traffic light, a male teenager in another car started yelling “Bin Laden, go back to your own country!” at him, and cut off Mukker when traffic started moving, a 2017 article in ProPublica says. The teenager got out of his car and started punching Mukker so hard, he broke his right cheekbone, damaged both his eyes and rendered him unconscious. Mukker is not the only Sikh cab driver who has been attacked because of his religious identity. In 2010, cab driver Harbhajan Singh attacked in West Sacramento by a passenger who shouted racial epithets at him, called him a Muslim and punched him in the face several times, a Reuters factbox of violent anti-Sikh incidents in the U.S. published in 2012 said.

Even in 2020, after the death of George Floyd, when the Black Lives Matter movement was gaining momentum, there were individual incidents of hate crimes against the Sikh community that occurred. A restaurant in the Sante Fe City of New Mexico, owned by a Sikh, was vandalized and broken into. Hate messages were scrawled across the walls of the restaurant, saying things like “White power,” “Trump 2020,” and “go home,” according to a CNBC report. At that point, it was the second incident of hate crimes against Sikhs in less than two months. On April 29, 2020, a 61-year-old Sikh American was brutally attacked by a man identified as Eric Breeman in Lakewood, Colorado. The attacker told Lakhwant Singh to “go back to your country” but no official hate crime charges were brought against him.

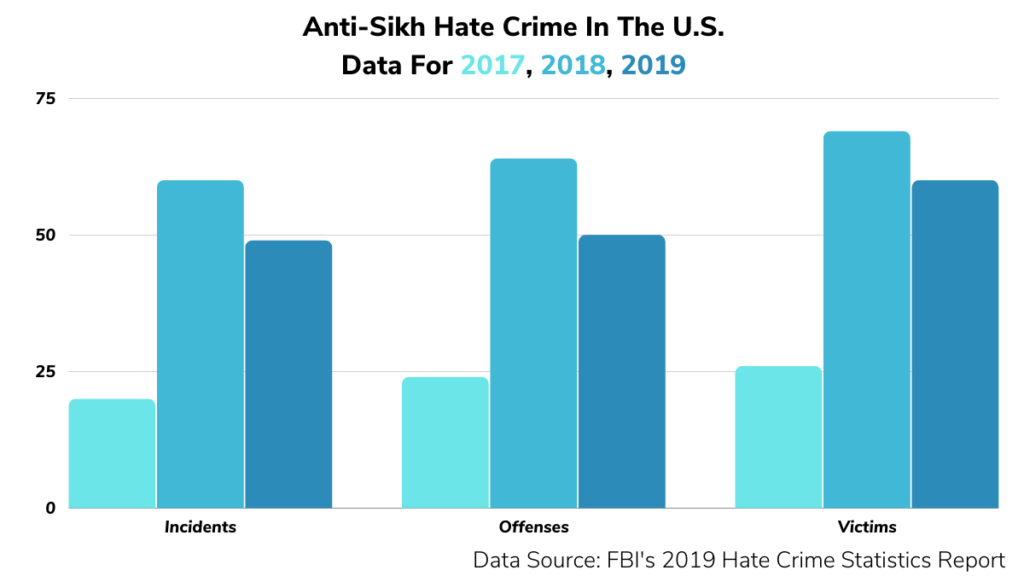

Since 2015, the Sikh Coalition has received an average of one legal inquiry per month related to anti-Sikh hate, it says in its 2020 year in review report. It was only in 2015 that the FBI added crimes against Sikhs to the national hate crimes database, the ProPublica article says. According to the FBI’s latest available Hate Crime Statistics report, which is for the year 2019, there were 49 anti-Sikh incidents reported in that year. When the FBI began collecting records of anti-Sikh crime, its data showed that there were six such offenses committed in 2015. But many Sikhs, including Harpreet Singh Saini, said back then that they believed the actual numbers were much higher.

Who is Saini, you may wonder. Saini lost his mother at the massacre at the Sikh temple of Wisconsin in Oak Creek in 2012. In the ProPublica article referred to above, Saini recalls his first day at community college where one of his teachers asked him and his classmates to get better acquainted by sharing stories of their summer vacations. When it was Saini’s turn, his story was this, the article says: “One month earlier, Wade Page, a neo-Nazi skinhead, murdered his mom and five other people. The whole thing happened just a mile-and-a-half down the road, during prayer services at the Sikh Temple of Wisconsin, a blocky beige building topped by five gold-colored minarets.” Six people were killed and three others were wounded by the gunman’s rampage on Aug. 5, 2012. The temple website’s homepage still carries photos of the six victims in remembrance.

The examples of hate are seemingly endless. Add firearm purchases to the mix, and the result appears to be tragedy after tragedy. The U.S. has had over a dozen mass shootings this year, and three just in Indianapolis. When it comes to last week’s FedEx shooting, for instance, the gunman was able to legally buy a firearm just months after he had his shotgun taken away. The two assault-style rifles that the gunman used in the attack were bought in July and September of 2020. Those purchases would have been possible only if a red flag determination had never been made, the New York Times report mentioned at the start of this piece said, citing the Indianapolis Police chief.

Despite all the hate, there are those within the Sikh community who have been striving to spread the message of love. When Saini testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee, he said he wanted to tell the gunman who killed his mother that he “may have been full of hate,” but his mother “was full of love.” In Valarie Kaur’s 2016 article, also referenced higher up in this piece, she goes on to describe a heartbreaking yet touching incident between Rana Sodhi and his brother’s killer, Roque.

Kaur asked Rana Sodhi if he would want to talk to Roque, if he had a chance to, in the spirit of reconciliation. Sodhi agreed and Kaur called Roque over phone. During the conversation, Roque told Sodhi: “One day, when I go to heaven to be judged by God, I will ask to see your brother, and I will hug him, and I will ask him for forgiveness,” according to Kaur’s article. Sodhi replied saying Roque had already been forgiven.