In The Heart Of Texas: A Child Advocate’s Story

By Kathy Nicholl

They meet in an unusual and rather unexpected setting — at a religious gathering. She takes her time and recounts to the judge in her child protection case what her father has done to her. The judge asks if she has told her advocate. In other places and to other people, her younger brother recounts what she has done to him as well. And yet, they both remain in the family unit with their parents. She is then about nine.

The court finally determines that she should be placed elsewhere, and her parents should have limited access.

The first placement is a self-contained treatment facility with dormitories and a school, and counsellors on staff. She has become so highly sexualized that she cannot stay in class without masturbating. The counselor recommends that she should be allowed to go to the restroom to relieve herself. The theory is that she should idealize a proper story to accompany the masturbation. She should visualize herself dressed in a bridal gown waiting on her husband.

For a year, her advocate requested a change of location.

The next placement center had a reward system in place that allowed two girls to live in apartments on the property after being awarded a particular number of points. At 12, she was allowed to live in one of these apartments. This center with the apartments was out in the country along the I-35.

And then, suddenly, she was taken from this placement to a small-town foster home that held 10 girls. The girls were encouraged to get jobs after school, handle their money, and get their driver’s licenses. At all these placements, she received counselling, schooling, medical care, and all that living requires — clothes, linens, cooking basics, chores, etc.

While at this placement, she attached herself to a young man in town with whom she decided to start a family. Because she was 17 by this time, she could leave the foster care system.

She had her first child with this man. By the time I lost touch with her, she had given birth to four babies, by four different fathers, and was living on the street in a city. She was then 22.

She was the first and longest running CASA case I had. After she left care, I was the advocate for her children.

Every Case Is Different

The other cases were not as hard, but each had its own complexities. I have had teenaged girls who ran from placements, decided to move in with older men, became violent and destructive in homes, did drugs, along with those that never relied on anyone but themselves.

But then there are others. I also had a case of five siblings that were fostered and adopted by a young couple who could not have children. The couple, in turn, were supported by a church filled with children and an extended family. Two of the children my first child birthed were adopted by their fathers. One was adopted by the father’s family.

It’s A Painful, Complex Process

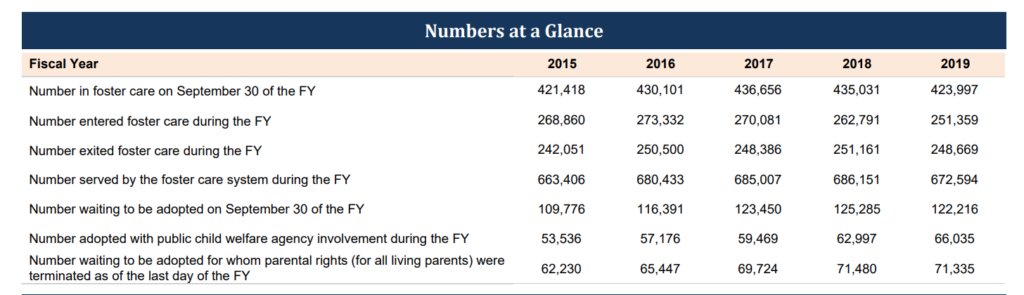

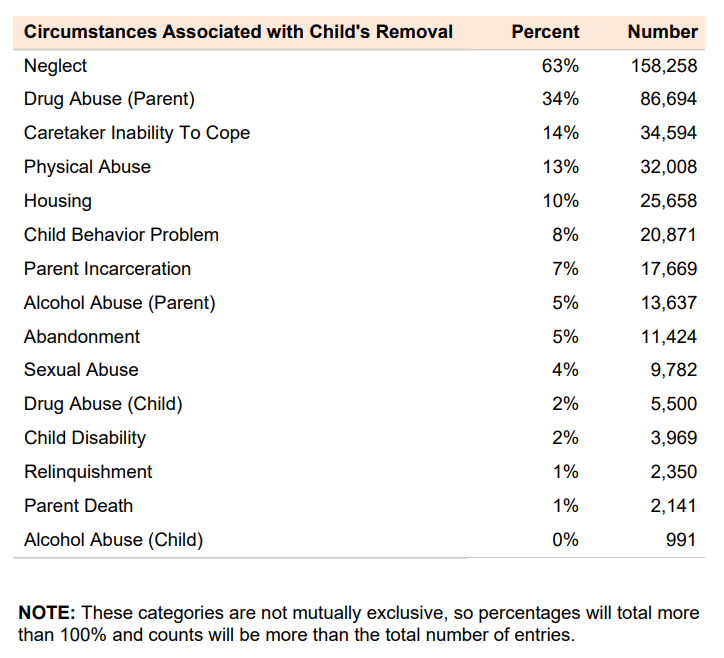

In 2019, approximately 424,000 children were in the foster care system in the United States. Of these, 158,258, or 63%, were there because of neglect, 34% because of a parental drug problem, 13% because of physical abuse, 7% because of parental incarceration, and 4% because of sexual abuse. Some had more than one cause listed as a reason for their removal from parental custody, which is why these numbers won’t make up a neat 100%.

The median age of these children was 7.7 years, but nearly one-third, or 31%, were under the age of three.

What is it like to be in foster care? What is the goal? When I was working with children, the goal was to stabilize the child’s life as soon as possible. The best case was that the child and parents would heal and be reunited. All parties would get counseling. The state set a limit of 18 months for parents to be able to support the family, provide a safe home, and get through any court-ordered requirements.

Why do courts want to send children back when possible? Because while a child is in care, nothing is stable. They are with people they don’t know. They are not allowed to be with a parent without a supervisor. They feel they have to tell people why they are not with their parents, but they really aren’t sure … and they are embarrassed and guilty. They think it is their fault that they are separated. They want to go back to their parents. When they see their parents, it is a stiff reunion in a strange room, with strange, stock furnishings, and a stranger watching. They do not have their own things at the placement.

Then they are told they can no longer see their parents. They are wards of the State. The State will determine where they live, who they see, what classes they take. In a normal setting, the parents give permission for going to birthday parties, for sleepovers. Now, even parents of “friends” need to pass a background check in order for the “friends” to visit. Granted, the State is responsible for the wellbeing of children, but if it is embarrassing for a child’s parents to ask what the friends’ parents do or where they live, imagine having to ask them to pass a background check! And how long does it take to set up the check and get the results?

One more thing. A child protection case worker and a CASA can also, typically, see a child in their school environment. A child can be pulled out of classes for these meetings. These are children who are usually behind in school. And their classmates know why they are being called out. Another source of embarrassment.

What’s the answer? Texas is under orders to get more foster parents and homes and have better systems in place. According to data sourced from the Department of Health and Human Services’s Children’s Bureau, for fiscal year 2018, 63,271 children in Texas were found to be victims of maltreatment, of which 42% of victims were found to be below the age of three. Only 56% received post response services, while the average time from the receipt of a report to the initiation of services was 59 days.

But the solution is not as easy as setting up tents. People need to have a calling to be a foster parent. They need to have training. They need to be able to support themselves and the children. The foster parent will need to have flexible enough schedules to take a child to all their counseling and medical appointments. They will need to take continuing education classes and be able to go to court monthly and meet with the child protection case worker and the CASA regularly. They will also need to take the children to meet with the case worker and advocate weekly.

After a year of isolation during the pandemic, unfortunately, cases have increased. There is also little doubt that cases have gone unreported because children have not left their homes. They have not seen by teachers and others in weeks.

The system has no answers. Not quite yet at least.

Note: Court Appointed Special Advocates (CASA) and Guardian Ad Litems (GAL) are appointed by courts to gather information and advocate in the best interests of children who have been abused, neglected or exploited. They are required to also keep the child’s wishes in mind while doing this. According to the National CASA/GAL Association, there are more than 93,000 volunteers nationwide, serving in 49 states and the District of Columbia.

(The writer served her local CASA organization in Texas, both on the Board and as an advocate, for 21 years. Although she no longer serves directly, she still supports the work. She is a retired mother/stepmother of five and grandmother of 10.)