Supreme Court Clarifies When Warrantless Searches And Seizures In The Home Are Justified

By Charlotte Spencer

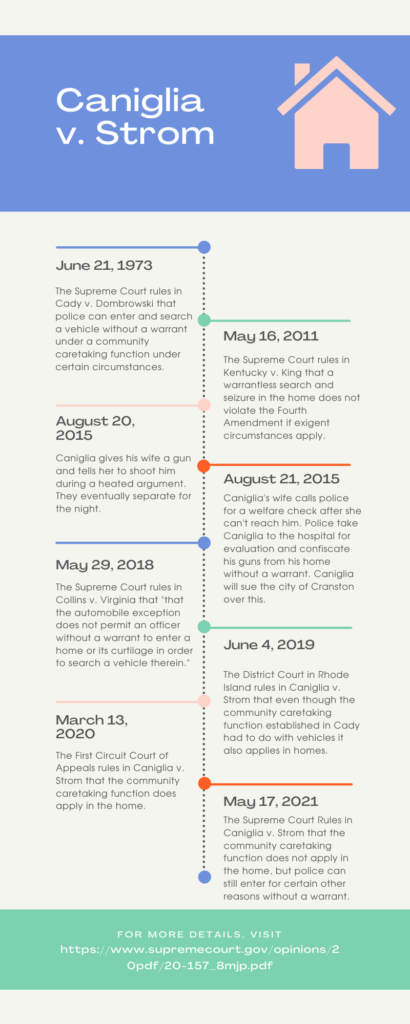

On Monday May 17, 2021, the Supreme Court issued a ruling further clarifying fourth amendment rights. The Fourth Amendment, and the long history of case law surrounding it, deals with search and seizure, specifically when it is allowed, and when it is not allowed. As a part of the Bill of Rights, it is important to individual freedoms central to our country. This case, Caniglia v. Strom, centered around a man whose guns were confiscated from his home by police without a warrant after his wife had called for a welfare check on him. The question before the court was whether this was allowed under a “caretaking” exception to the Fourth Amendment established in earlier case law.

What Does The Fourth Amendment Say?

“The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.”

What Happened?

It all started when Edward Caniglia and his wife, Kim Caniglia, got into an argument. He left the dining room of their home, where the argument was occurring, got a gun from the bedroom, returned and placed it on the table before her. He then asked her, “why don’t you just shoot me and get me out of my misery.” He left after she threatened to call 911. She then hid the gun, and noticed that it had never been loaded in the first place. When he returned they continued their argument. She decided to leave for the night and get a hotel room. The next morning, when she tried to reach him by phone, she could not. This alarmed her because of the suicidal thoughts which he had expressed the night before. She called the police to request a welfare check. Police went with her to the house to check on her husband, where they found him sitting on the front porch. Although he claimed that he was not suicidal, he did confirm that his wife’s account of the argument was correct, and that he had asked her to shoot him. Police decided, based on this, that they should take action, even though they did not have a warrant, because they believed that he posed a risk to himself or others.

What happened next would become the subject of the court cases that would follow. Caniglia agreed to get in the ambulance and go to the hospital for a psychiatric evaluation only after police agreed not to confiscate his guns. Once he had gone, his wife let police into the house and guided them to the guns so that they could confiscate them. Caniglia alleged that police had gotten her to do this by misinforming her about his wishes. He sued, claiming that they had violated his fourth amendment rights by seizing him, and entering his home and seizing his guns without a warrant.

What Were The Arguments?

Pro-Confiscation

The District Court, who first heard the case decided mostly in favor of the police and granted summary judgement to the city on all but one of the counts, reasoning that “the City operated within its duties to care for the community during the well-being check on Mr. Caniglia and his family.” The city argued that police did not violate Caniglia’s fourth amendment rights because they did not stop or arrest him for law enforcement purposes, but rather in “furtherance of their duties under the community caretaking function.” The District Court agreed with this reasoning. In reaching this decision they relied on case law from several cases, including Cady v. Dombrowski, in which the Supreme Court recognized the distinction between law enforcement functions and community caretaking functions conducted by police. The District Court did, however, acknowledge in a footnote of their opinion that “Mr. Caniglia correctly points out that courts are split about whether the community caretaking function standard the United States Supreme Court first set forth in Cady in the vehicle context also applies to searches of a home…”

Caniglia appealed this decision to the First Circuit Court of Appeals. The First Circuit Court affirmed the District Court’s ruling, reasoning “the actions of the defendant officers, though not letter perfect, did not exceed the proper province of their community caretaking responsibilities.” The First Circuit also cited Cady v. Dombrowski, arguing that, “Given the doctrine’s core purpose, its gradual expansion since Cady, and the practical realities of policing, we think it plain that the community caretaking doctrine may, under the right circumstances, have purchase outside the motor vehicle context.”

Anti-Confiscation

The District Court, who first heard the case decided in favor of Caniglia on one of the counts, reasoning that “The City infringed on Mr. Caniglia’s rights when it refused to return his property and failed to provide him with any process of how to get it back after his health and safety were secured.” At the point when his health and safety were secured, in other words, the community caretaking function would no longer apply.

Caniglia argued in the District Court case, the Appeals Court case, and the eventual Supreme Court case that the police had no right to transport him to the hospital, or to enter his home and take his guns in the first place. He reasoned that “Neither the United States Supreme Court nor the Rhode Island Supreme Court have ever authorized the use of the CCF [community caretaking function] to seize people or property from a home.”

What Did The Supreme Court Rule?

The Supreme Court ruled unanimously in favor of Caniglia. Like Caniglia, the Supreme Court drew a distinction between vehicles and the home when it comes to the community caretaking function. As stated in the Court’s conclusion: “What is reasonable for vehicles is different from what is reasonable for homes. Cady acknowledged as much, and this Court has repeatedly ‘declined to expand the scope of . . . exceptions to the warrant requirement to permit warrantless entry into the home.’ Collins, 584 U. S., at ___ (slip op., at 8).” In other words, the Supreme Court in no way overturned what had been established in Cady. The Court simply clarified that this case law applied only to the original circumstances it dealt with, that being search and seizure as it relates to vehicles. As the Court pointed out, vehicles often have to do with the noncriminal community caretaking function of police when they are disabled on a roadway or involved in accidents, but this does not apply to houses. By contrast, the law and culture in the United States has always been particularly protective of privacy in the home.

What Does This Mean For The Average Person?

First, this does not mean that there are never circumstances under which police or other law officers can enter the home without a warrant. Like anyone else they can, of course, enter when invited. They can also enter under “exigent circumstances.” In other words, they can enter for an emergency. For example, they can enter when a person is in immediate danger and there is no time to get a warrant. This was not the case here.

This ruling means that police cannot apply the community caretaking function to enter a home and seize property without a warrant. They can, however, still do this with a vehicle as case law had already established.

What Did Individual Justices Have To Say About It?

Although the ruling was unanimous, some Justices took the time to write concurring opinions. Here is a short overview.

Roberts

Justice Roberts joined the majority opinion, but took time to clarify that he joined that opinion because nothing in it contradicted the Court’s earlier rulings in Brigham City v. Stuart, 547 U. S. 398, 406 (2006). “A warrant to enter a home is not required, we explained, when there is a ‘need to assist persons who are seriously injured or threatened with such injury.’”

Alito

Justice Alito wrote separately to clarify several points. These points mainly had to do with clarifying questions which the Court did not decide in its ruling so as to limit later overly-broad interpretations of the ruling. He pointed out that the Court was not deciding questions involving state laws allowing emergency seizure for psychiatric evaluation, questions involving state “red flag” laws that allow police to seize guns pursuant to a court order to prevent harm, or questions involving cases where police enter without a warrant to ascertain a possible medical emergency.

Kavanaugh

Justice Kavanaugh also wrote separately to clarify that this decision was not a broad decision banning entry without a warrant in every circumstance, and listing some examples where this would still be allowed, such as emergencies.

This article was last updated May 19, 2021. The information provided in this article should not be considered legal advice or a substitute for legal advice. Biometrica is not a law firm and cannot offer legal advice.