The Dark Side Of The Web: Drug Trafficking On The Darknet Grew Nearly Fourfold Recently

By Deepti Govind

At the end of last month, a drug dealer called Chukwuemeka Okparaeke, whose online darknet avatar is “Fentmaster,” was sentenced to 15 years in prison. He imported and trafficked fentanyl analogues and other synthetic opioids through the dark web, including one controlled substance called U-47700 that he sold to an 18-year-old individual who died from an overdose after using the drug. Okparaeke used the dark web marketplace AlphaBay to peddle his drugs between 2016 and 2017, engaging in over 7,000 sales of synthetic opioids.

The “Fentmaster,” who attended medical school before he turned into a darknet drug dealer, shipped these drugs to customers throughout the country using the U.S. Postal Service. He used extensive measures to conceal his identity, including software to encrypt his internet traffic and the communications sent from his cellphone. Using alter egos, he boasted online about his exploits as a darknet drug trafficker, offered advice to other drug dealers and even publishing a short story describing his criminal activities and his strategies for evading law enforcement.

It took the combined efforts of the U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), Homeland Security Investigations (HSI), the United States Postal Inspection Service (USPIS), the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), and multiple other law enforcement agencies to investigate Okparaeke’s case. During just one search of a premises he maintained, law enforcement agencies seized over 10 kilograms of U-47700, acryl fentanyl, and furanyl fentanyl, as well as a quantity of 4-ANPP (despropionyl fentanyl) and roughly 82 mailing envelopes containing smaller amounts of those substances that had been packaged for his customers.

This is just one case of a single darknet drug dealer.

Major drug markets on the dark web are now worth around $315 million annually, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) said in a report. From 2011 all the way until mid-2017, drug markets on the dark web were estimated to be worth around $80 million in annual sales. But, in under three years since (i.e., between mid-2017 to 2020), there’s been a near 300% increase in growth in the size of this market (i.e., to $315 million). What makes this more important is the fact that drug markets on the dark web only emerged a decade or so ago.

As with everything else during the year of the Covid-19 pandemic, contactless drug peddling was identified as an accelerating trend. Even before Covid-19, though, the accessibility of drugs had begun widening, with dealers turning to social media and even popular e-commerce platforms to peddle their wares. Currently it is cannabis, which has been fully legalized across several states in the U.S., that dominates darknet sales. Meanwhile, marketing on the “clear web” often involves new psychoactive substances (NPS) and those used in the making of synthetic drugs, including precursor chemicals.

A study conducted in 2016 by research firm Terbium Labs found that of the close to 200 domains it catalogued as illegal out of 400 randomly selected darknet sites on the Tor (The Onion Router) network, over 75% were marketplaces. Recreational and pharmaceutical drugs were the most popular products on these marketplaces, followed by stolen and counterfeit documents such as identities, credit cards, and bank credentials, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) said of the Terbium Labs study in a blog published in September 2019.

Before we delve a little more into the UNODC’s recent findings, here’s a quick explainer on darknet marketplaces and how they evolved.

Darknet Drug Marketplaces

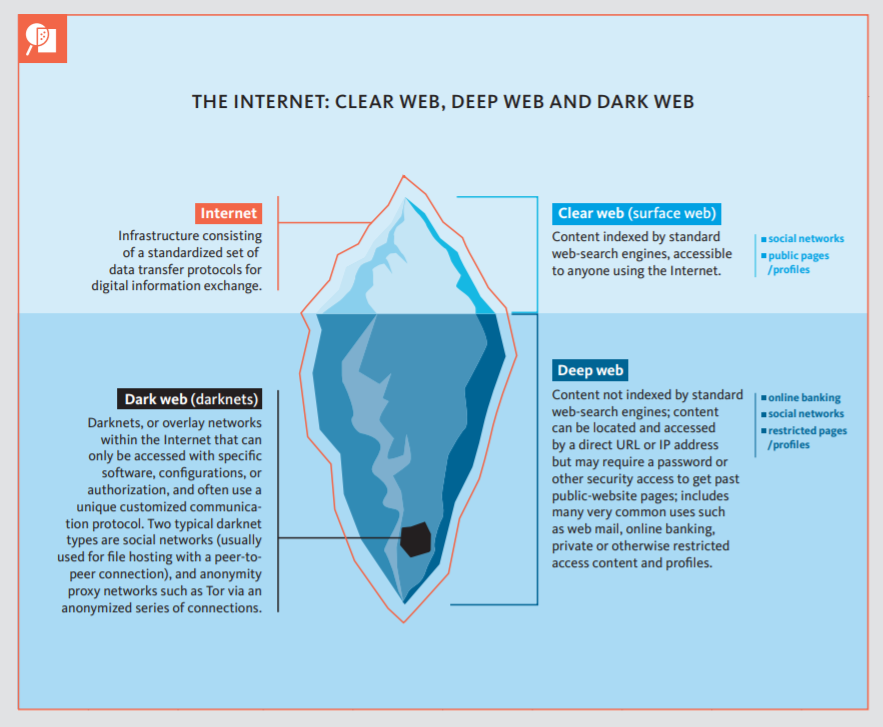

A darknet marketplace is no different, really, in the way it is meant to operate when compared with regular online marketplaces that most of us are familiar with like Amazon or eBay. The main difference, of course, is that darknet marketplaces give their users anonymity. These marketplaces, and the dark web itself, can be accessed through various ways — including by using platforms like Tor, a browser that can be downloaded for free. Tor offers up a collection of sites (with .onion addresses) inaccessible via a regular browser and not indexed by search engines like Google, as the IMF blog explains.

Then there are mirror sites on the surface web that provide hyperlinks to corresponding hidden sites, and “invitation-only” markets where users need to be referred by a current user, the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) says.

“The earliest modern online anonymous markets, often referred to as darknet markets or cryptomarkets, appeared in early 2010, and evolved from an encrypted email service and migrated on to a Tor anonymity network to guarantee better anonymity to users. The first darknet market of notoriety was Silk Road, which opened at the end of January 2011 and was seized by the FBI in October 2013. Silk Road 2.0 was launched soon after the original Silk Road was seized and since that time there has been a proliferation of darknet markets,” the EMCDDA website adds.

Specialized “darknet explorers” enable customers to access their desired market platform, where goods are then typically paid for in cryptocurrencies — in particular bitcoins — which can be used subsequently to buy other goods and services, or can be exchanged for various national currencies. The delivery of drugs purchased on the darknet is generally carried out by public and private postal services without their knowledge, with parcels often being sent to anonymous post office boxes, including automated booths, or “pack stations” for self-service collection. In jurisdictions with strong secrecy-of-correspondence laws, drugs are often dispatched in letters, the report adds.

Cut to today, where the pandemic has pushed everything online, where technological advances are only becoming more rapid, and where criminals are constantly becoming more agile and adapting to these new technologies, and it’s possible that we could soon see a globalized market where all drugs are more available and accessible everywhere. “This, in turn, could trigger accelerated changes in patterns of drug use and entail public health implications,” the UNODC report says.

What makes the darknet a conducive platform for drug trafficking is the anonymity of the transaction, the fact that no physical contact is required, that it takes away hesitance among some consumers who may have otherwise been reluctant to interact with drug dealers, and that it also removes the obstacle of consumers having to go to potentially dangerous or lonely places to buy the drugs. It also means sellers and buyers need not be in the same location — hence the fear that it could become a globalized market, as we mentioned earlier.

The other advantage of not having to be in the same location is that drug dealers who sell over the dark web do not need a critical mass of customers to sustain themselves like they do with a localized market. And, as with other online marketplaces, customers can also view feedback about the quality of drugs sold by suppliers, once again making it all the more easier for the illegal drug market to thrive.

Thus, the very nature of the dark web that makes it a useful tool for those who could otherwise be endangered by revealing their identities online, like victims of abuse and persecution or whistleblowers, has been turned on its head and has become an unintentional advantage that criminals are exploiting too. The good news is such platforms do not really last long, per the UNODC report.

An analysis of 103 darknet markets over the period 2010–2017 revealed that they were active for, on average, just over eight months, the report says. A similar analysis showed that of more than 110 darknet drug markets that were active during 2010–2019, just ten remained fully operational in 2019. Most of them were only started in 2018, and almost all of those that became major darknet markets had disappeared by December 2020. Without intervention from law enforcement, the dynamic and resilient darknet market ecosystem could have grown even faster over the past decade. But major law enforcement operations have led to the dismantling of a number of darknet platforms, including AlphaBay, which we mentioned at the beginning of this piece when talking about the “Fentmaster” case.

Still, more needs to be done to combat this rising trend. Although darknet marketplaces have a tiny share of the overall illegal drug-market pie, their very nature could make them tougher to crack, as we saw in the “Fentmaster” case. Public–private partnerships need to be forged with participation from internet service providers, tech companies, and shipping and mailing companies to improve government response to drug trafficking on the internet, the UNODC report says. The internet drug supply-chain has to be controlled, drug adverts and listings need to be removed, information must be shared with law enforcement, cryptocurrency markets have to be regulated, electronic payments must be monitored, and expert access to the dark web needs to be enhanced to take down illegal online markets and platforms, the report adds.

This is part one of a series Biometrica plans to do on the dark side of the web. Up next in this series will be an even deeper look at the world of illegal darknet drug trafficking.