The First Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Report Acknowledges A Shrouded Legacy

By a Biometrica staffer

One-and-a half centuries. Over 400 Indigenous boarding schools run by the federal government, with support from religious institutions. The use of systematic militarized and identity-alteration methodologies in an attempt to ‘assimilate Indigenous persons.’ Corporal punishment to enforce rules at these schools. 53 burial sites and over 500 deaths identified so far, with the count expected to increase. That’s the heartbreaking and undeniable shrouded legacy the U.S. acknowledged on May 11, Wednesday.

Department of Interior (DOI) Secretary Deb Haaland tweeted about a crucial announcement on Wednesday. “Today, from the ancestral homelands of the Anacostan and Piscataway people, I provided remarks on the history of federal Indian boarding schools in this country and our work on the Federal Boarding School Initiative,” she said in the first of a series of tweets. Haaland and Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs Bryan Newland released Volume 1 of the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative yesterday.

The 106-page investigative report is “a comprehensive effort to address the troubled legacy of federal Indian boarding school policies,” the DOI statement says. It also lays the groundwork for the continued work of the DOI to address the intergenerational trauma created by historical Federal Indian boarding school policies. The announcement and the report acknowledge the large-scale and violent treatment of Indigenous students at 408 Indian boarding schools run by the federal government between 1819 and 1969.

During that timeframe, these schools were present across 37 states (or then-territories), including 21 schools in Alaska and 7 schools in Hawaii. The report identifies each of those schools by name and location, some of which operated across multiple sites. The investigation identified marked or unmarked burial sites at approximately 53 different schools across the school system. As the investigation continues, the Department expects the number of identified burial sites to increase.

The DOI’s statement says the report is a: “significant step by the federal government to comprehensively address the facts and consequences of its federal Indian boarding school policies — implemented for more than a century and a half — resulting in the twin goals of cultural assimilation and territorial dispossession of Indigenous peoples through the forced removal and relocation of their children. It reflects an extensive and first-ever inventory of federally operated schools, including profiles and maps.”

Secretary Haaland, the first Native American to serve as a cabinet secretary, echoed those sentiments in her series of tweets: “The languages, cultures, religions, traditional practices and even the history of Native communities… all of it was targeted for destruction. Nowhere is that clearer than in the legacy of federal Indian boarding schools … The consequences of federal Indian boarding school policies—including the intergenerational trauma caused by forced family separation and cultural eradication—which were inflicted upon generations of children as young as 4 years old are heartbreaking and undeniable.”

“Many children never made it back home. Each of those children is a missing family member, a person who was not able to live out their purpose on this earth because they lost their lives as part of this terrible system. The Biden-Harris administration is determined to make a lasting difference in the impact of this trauma for future generations. Today, we take a critical step forward in that work,” DOI Secretary Haaland said in her tweets.

In June 2021, Haaland announced the “Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative,” at a conference of the National Congress of American Indians, the country’s largest coalition of Indigenous Peoples. The Initiative was launched to undertake a “comprehensive review of the troubled legacy of federal boarding school policies.” The DOI has been historically tasked with monitoring and looking after the country’s Indigenous population. The DOI is responsible for honoring the federal government’s treaties with the 574 federally recognized Indian tribes and Native Alaskan villages. Last June, Secretary Haaland said that as the primary force behind the management of these schools, the DOI was “uniquely positioned to assist in the effort to recover the histories of these institutions.”

What the DOI published yesterday was the first report from that initiative. We bring you some key highlights from the report in the rest of this piece. Given how comprehensive the report is, this will be the first in a mini series of articles Biometrica will do on it.

Federal Indian Boarding Schools Defined

To begin with, the report confirms that the U.S. directly targeted American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian children in the pursuit of a policy of cultural assimilation that coincided with Indian territorial dispossession, Bryan Newland, Assistant Secretary – Indian Affairs said in the report. It further identifies the Federal Indian boarding schools that were used as a means for these ends.

For a school to qualify as a Federal Indian boarding school, for the purpose of this investigation, the institution must meet four criteria, the report says, including whether the institution:

- Housing: The institution has been described as providing on-site housing or overnight lodging. This includes dormitory, orphanage, asylum, residential, boarding, home, jail, and quarters.

- Education: The institution has been described as providing formal academic or vocational training and instruction. This includes mission school, religious training, industrial training school, manual labor school, academy, seminary, institute, boarding school, and day school.

- Federal Support: The institution has been described as receiving Federal Government funds or other Federal support. This includes agency, independent, contract, mission, contract with white schools, government, semi-government, under superintendency, and land or buildings or funds or supplies or services provided.

- Timeframe: The institution was operational before 1969 (prior to modern departmental Indian education programming including BIE, or Bureau of Indian Education).

Outside the scope of the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative, the DOI identified over 1,000 other Federal and non-Federal institutions, including Indian day schools, sanitariums, asylums, orphanages, and stand-alone dormitories that may have involved education of American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian people, mainly Indian children, the report adds.

The earliest opening date of a Federal Indian boarding school in the system was 1801, and the latest opening date was 1969. However, the open date does not necessarily correspond to when the Federal Indian boarding school was first documented as receiving Federal support. Present-day Oklahoma had the highest concentration of schools in the Federal Indian boarding school system with 76 such schools, or 19% of the total number. Arizona ranked second with 47 schools, or 12% of the total, and New Mexico was third with 43 (or 11%).

Initial investigation results show that about 50% of Federal Indian boarding schools may have received support or involvement from a religious institution or organization, including funding, infrastructure, and personnel, the report says. At times, the Federal Government paid religious institutions and organizations on a per capita basis for Indian children to enter the Federal Indian boarding schools that these institutions and organizations groups operated.

Investigation also shows that the U.S. may have used monies held in Tribal trust accounts, including those based on cessions of Indian territories to the U.S., to fund Indian children to attend Federal Indian boarding schools, per the report.

The Identity-Alteration Tactics Used On Children

Often using active or decommissioned military sites, Federal Indian boarding schools “were designed to separate a child from his reservation and family, strip him of his tribal lore and mores, force the complete abandonment of his native language, and prepare him for never again returning to his people,” the report says. Given this design, the U.S. applied systematic militarized and identity-alteration methodologies in these schools to assimilate American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian children through education.

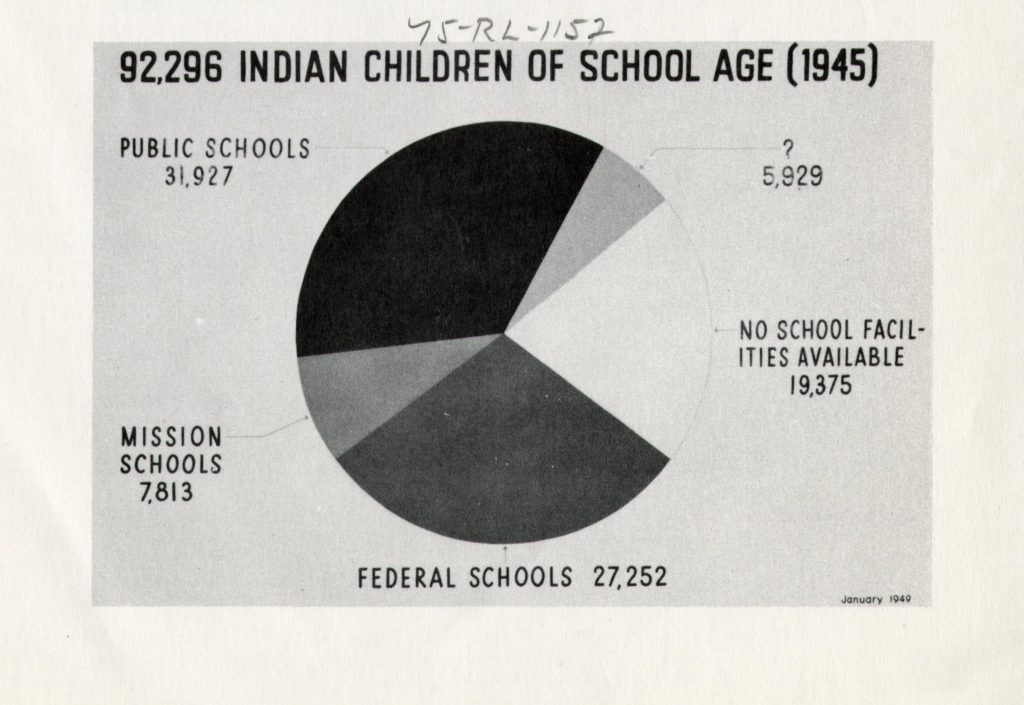

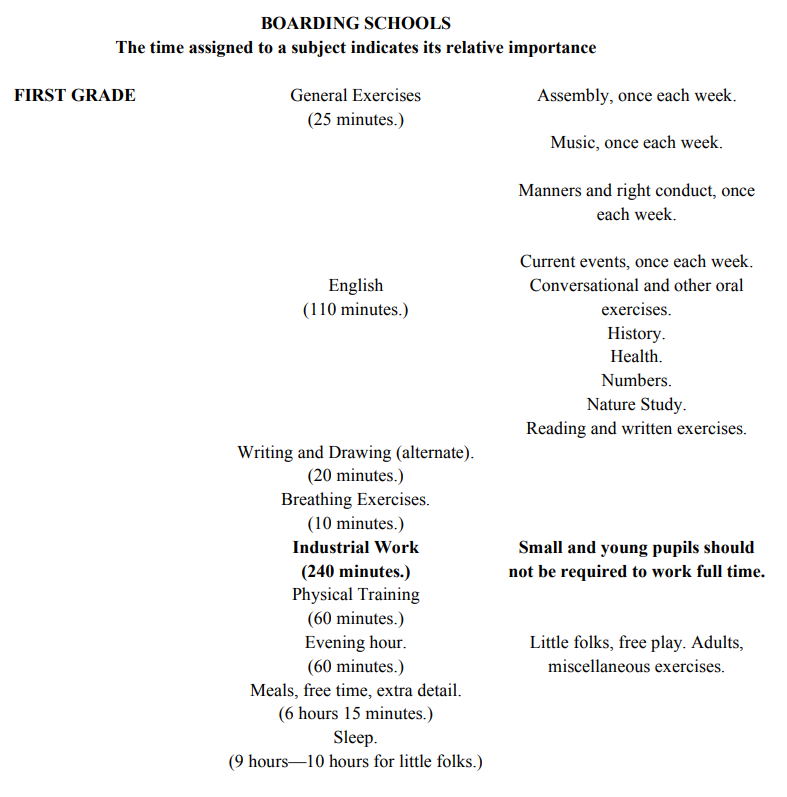

Generations of Indigenous children, separate and together, experienced the Federal Indian boarding school system, which Congress recognized was “run in a rigid military fashion with heavy emphasis on rustic vocational education,” the report adds. Emphasis was placed more on teaching the children habits than learning from books. For instance, the children were taught obedience, cleanliness, and given “a better carriage.” Their 24 hours was so systemized that there “was little opportunity to exercise any power of choice,” the report says. Below is an example of the curriculum for first grade students across the Federal Indian boarding school system in 1917:

Schools used various methods to systematically alter the identity of the children. Some of those methods include:

- Renaming Indigenous children from Indigenous names to different English names

- Cutting the hair of Indigenous children

- Requiring the use of military or other standard uniforms as clothes

- Discouraging or forbidding certain practices in order to compel them to adopt western practices and Christianity. Those include using Indian languages, conducting cultural practices, and exercising their religions.

This quote from archived documents in the report sheds further light on the situation at these boarding schools: “When first brought in they are a hard-looking set. Their long tangled hair is shorn close, and then they are stripped of their Indian garb thoroughly washed, and clad, in civilized clothing. The metamorphosis is wonderful, and the little savage seems quite proud of his appearance.”

Children were not permitted to study any other language than “our own vernacular – the language of the greatest, most powerful, and

enterprising nationalities beneath the sun,” the report says. The first step in the training of the children was to teach them English.

Corporal Punishment & Runaways

Rules at these boarding schools were often enforced through punishment, including corporal punishment, such as solitary confinement, “flogging, withholding food, … whipping,” and “slapping, or cuffing.”

“At times, rule enforcement was a group experience: “for the first offense, unless a serious one, a reprimand before the school is far better than a dozen whippings, because one can teach the whole school that the offender has done something that is wrong, and they all know it and will remember it, while it is humiliating to the offender and answers better than whipping,” the report adds.

Sometimes, in order to “conduct discipline,” Federal Indian boarding schools also made older children punish younger ones. The report sheds more light on this practice by quoting from archives: “When offenses have been serious enough to demand corporal punishment, the cases have generally been submitted to a court of the older pupils, and this has proved a most satisfactory method.”

Initial analysis suggests that there was a trend of Indigenous children escaping and running away from these schools. Those who did were “promptly brought back and punished,” judiciously. The DOI has recognized that, for instance, runaways were frequent during the first half of the year at the Kickapoo Boarding School, Kansas. Corporal punishment was resorted to with the belief that: “a prompt returning of the runaways and a whipping administered soundly and prayerfully, helps greatly toward bringing about the desired result.”

Grossly Inadequate Provisions

Provisions for the care of Indigenous children at these schools has been considered grossly inadequate by the DOI. Rampant physical, sexual, and emotional abuse; disease; malnourishment; overcrowding; and lack of health care in Indian boarding schools are well-documented, the report says. For example, at White Earth Boarding School, Minnesota, the ratio was one bed to two pupils. Similarly, at the Kansas Kickapoo school, the ratio was three children to each bed. At Rainy Mountain Boarding School, Oklahoma, single beds were pushed closely together and each bed had two or more occupants.

When the number of children at these schools expanded even beyond those cramped arrangements, schools would resort to increase dormitory capacity without any major expenditure involved by adding sleeping porches. But these porches shut off light and air from the inside rooms, which are already filled beyond capacity.

In many cases, even as the number of students increased, toilet facilities did not. They were also frequently not properly maintained or conveniently located, while the supply of soaps and towels were also inadequate. When it comes to diet, too, the Federal Indian boarding schools lacked. Poor diets that were high in starch and sugar and low in fresh fruits and vegetables were common in the system.

Child Labor

“The labor of [Indian] children as carried on in Indian boarding schools would, it is believed, constitute a violation of child labor laws in most states,” the Meriam Report, made at the request of the Secretary of the Interior in 1928 said. The boarding school system focused on vocational training, involving the manual labor of Indigenous children.

In 1902, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs described that to “educate the Indian is to prepare him for the abolishment of tribal relations, to take his land in severalty, and in the sweat of his brow and by the toil of his hands to carve out, as his white brother has done, a home for himself and family,” the report says.

Some of the manual labor practices children at these schools were engaged in include:

- Livestock and poultry raising

- Lumbering

- Working on the railroad

- Carpentering

- Blacksmithing

- Fertilizing

- Irrigation system development

- Well digging

- Making furniture

- Cooking

- Laundry and ironing services

- Garment making

For example, in 1857, girls at the Winnebago Manual Labor Schools, Nebraska, made 550 garments for themselves and the boys attending the school, and some 700 sacks for the use of the farm. In 1903, boys at the Mescalero Boarding School, New Mexico, sawed over 70,000 feet of lumber and 40,000 shingles and made upward of 120,000 brick.

Biometrica will continue to explore the report in follow-up posts as part of this mini series. For information on Biometrica’s own efforts towards helping to solve the crisis of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Persons, click here.