Securing Our Security In A Brave New World

By Wyly Wade

Last month, NIST, the National Institute of Standards and Technology, released an initial version of a framework of standards to help developers of cyber-physical systems (CPS) build cybersecurity and privacy into their designs. This week, NIST announced that their Smart Grid Advisory Committee would have an open meeting over July 13-14, to update the public on NIST’s Smart Grid and CPS initiatives, and discuss resilience and reliability issues related to cyber-physical systems.

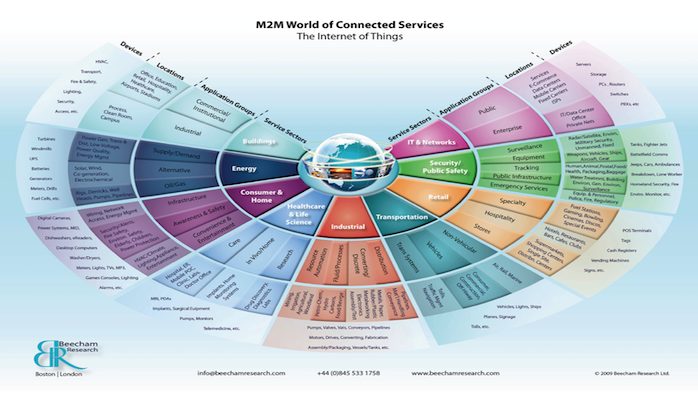

If you’re reading this, you’ve probably heard the term “the Internet of Things” — that world where the physical and digital meet and merge, and make magic happen. Sort of.

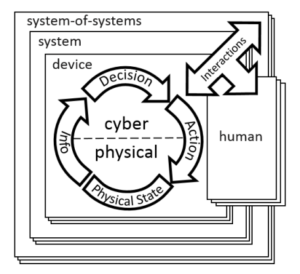

The NIST defines CPS (see NIST CPS image on the right), sometimes used interchangeably with the IoT, more properly: As “smart systems that include engineered interacting networks of physical and computational components.”

This, by the way, includes anything from your smart watch to smartphone to new generation cars, to intelligent buildings, Smart Grids — computerized electric utility grids equipped with two-way communication technology — and a whole bunch of things in between that range from consumer items to critical infrastructure.

Why Do We Need A Discussion On Resilience And Reliability?

Well, imagine this. A criminal element, or a rogue foreign power, takes control of your local power station. In a different era, it would all have had to be done through surgically planned physical strikes on a substation, taking out multiple transformers. That, unfortunately, still happens. But with Smart Grids — a Rogue element X, this could be human, humanoid, a virus, even a bad line of code, could use that same technology to create chaos.

Think of Ukraine in December 2015, where the first publicly acknowledged and proven hacking of a power grid happened. Where, as this great article in Wired puts it, inside a control center of a power distribution entity, all an operator could do, “was stare helplessly at his screen while the ghosts in the machine clicked open one breaker after another, eventually taking about 30 substations offline.” That BlackEnergy malware attack eventually affected power to about 230,000 people.

As technology rapidly changes our world, and we just begin to understand the scope of the IoT and cyber-physical systems, we have understood that it’s not just utilities or manufacturing facilities, or military or civilian bases that can be electronically invaded. From smart locks for homes to remote keys for cars, from pre-op pods in hospitals to intelligent buildings and other M2M (machine to machine) technology, as everything in our own lives is customized digitally, how easy would it be for someone to invade your life?

- Or turn off the heat in your home in sub-zero temperatures in a Wyoming winter?

- Or open up the gates to a Supermax prison facility?

- Or switch off the power, and generator backup to the ER at a busy hospital?

- Or hack into an ATM or bank account to get all your details?

- Or send an elementary school into lockdown with a miscreant inside?

- Or take over the controls of your car, or bus, or plane?

What Do We Do Next?

We secure our systems. And come back to establishing that our CPS are resilient and reliable. With a view to this, historically, there are three basic ways of securing physical or digital access, or the process of validating information to make something secure. These are

- The things that you know

- The things that you have

- The things that you are

Historically, we used one of these points to validate information or grant access, or linked two of those in a two-step authentication process. We asked for someone’s name, or date of birth. We then added “the things that you are,” say, your biometrics, to “the things that you have,” like your driver’s license, into the mix. When you think about the process of somebody looking at your ID, they’re trying to validate that photo looks like you. In the case of a website with PII, on the other hand, it could be a combination of your name and a secret question (“the things that you know”) needed to validate access.

More recently, a third dimension was added, even to digital access — a process through which the person granting access could confirm that the picture on your ID was the person they were talking to, by your using biometrics on your laptop or smart phone.

All of this is at the level of an individual, but try and step back and picture this on a larger scale. We are now at the point where, if someone is attacking you, they’re not attacking you to try and steal information only specific to you. They are attacking you, typically, to gain access to your cyber-physical systems and those systems and networks they, in turn, grant you access to, to create disruption in a wide variety of areas.

This could be a disruption of service reputation, a disruption of physical access, perhaps a disruption of power production — something that is very visible, but unpredictable.

With Malice Toward All

Whether it was the Ukraine power crisis, the SWIFT attacks, or the data breaches at the DNC, including the most recent one, all of these were people of various stripes using digital systems to cause disruption in the physical world.

In some cases, the malice is extreme. When someone hacked the electric grid in Ukraine, it was to show how vulnerable systems are, and how easy it would be to reach out and touch, even terrorize, a quarter of a million people.

And it is about terror; it is about gaining digital access to a soft target to influence the most common or basic elements of the physical world, causing questions to creep in about the basic principles of safety and security, cause primal fear, pervert your normal sense of self, and result in an irrational response.

Protecting Our Brave New World

There is no question that technology brings positive change, and that cyber-physical systems allow us to lead better lives, leading to the evolution of Smart Cities, being more fuel efficient, and less negatively impactful on land, among other things. However, there is also no question that the further we travel down the IoT, and the further we get to the standardization of cyber-physical systems, a single vulnerability, even a remote one, will have a much larger impact than ever before on the way we live.

With that in mind, we can try and get the basics right. As NIST, or anyone else, goes down the path of standardization and building processes that protect and guide cyber-physical systems, they would be looking at building those around versions of these three fundamental points:

- Have multi-factor authentication to verify physical access to something: Where verifying access is a combination of Who You Are, What You Have and What You Know.

- Limit the way access to data is allowed in shared systems: Where we deal with complex, dynamic environments by limiting data access to people with a combination of flexible, on-a-need-to-have basis of role-based and access-based controls (RBAC and ABAC), and separate the policy aspect of data from the technical management of a system. Essentially, create networks, systems and products where every role does not have access to all the data or systems traditionally connected to having that role.

- Maintain commonsense security hygiene to restrict physical access to your computational systems: Lock doors. Lock cars. Use passwords to access your laptops or other devices, and use robust password management. Why? Because in a connected world, once someone has physical access to you, they pretty much “own” you, and it takes a world of effort and heartache to change that state of things.

We are undoubtedly at the very beginning of a very different world, a better one, but a more vulnerable one. The path to rethinking our new, connected, digital-meets-physical world order, to make it safer and more secure, is not easy, and we do have many miles to go before we will collectively sleep easier, and breathe easier. It isn’t just a path less traveled, it is a path never traveled. But it is the path that needs to be taken.

(This article was first published on LinkedIn Pulse, here. Wyly Wade is CEO & President of Biometrica Systems, Inc.)