Trending Back To Business? Suspicious Activity Reports For Casinos Spike In Q1 2021 After 2020 Decline

By a Biometrica Staffer

According to the American Gaming Association’s (AGA) Commercial Gaming Revenue Tracker, 2020, the year that life came to a virtual standstill on account of the coronavirus pandemic, marked the first market contraction for the U.S. gaming industry since 2014 and the lowest gaming revenue total since 2003. U.S. commercial gaming revenue totaled $30.0 billion in 2020, down more than 31% year-over-year. Against this backdrop, it was unsurprising that the year also saw fewer Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs) filed by casinos — commercial and tribal — and card clubs than any other year in the recent past.

The Financial Crimes Enforcement Network or FinCEN’s SAR Stats tells us that for the year 2020, there were a total of 39,480 SARs filed by casinos and card clubs. Of these, 12,891 were entries by tribal authorized casinos, 25,162 by state-licensed casinos, 1,302 by card clubs and 125 by other casino/card clubs.

2020 SARs (Casinos/Card Clubs)

- Jan – 4,519

- Feb – 4,418

- March – 4,067

- April – 1,024

- May – 352

- June – 1,298

- July – 3,659

- Aug – 3,697

- Sept – 4,067

- Oct – 4,360

- Nov – 3,914

- Dec – 4,105

Source: FinCEN SAR Stats

On the plus side, things might be getting back to normal for the gaming industry, if the filing of SARs is an indication of matters. For the first three months of 2021 so far, we’ve had a total of 11,968 SARs filed, of which 174 SARs have been by card clubs, 21 by other casino/card clubs, 7,293 by state-licensed casinos, and 4,480 by tribal authorized casinos.

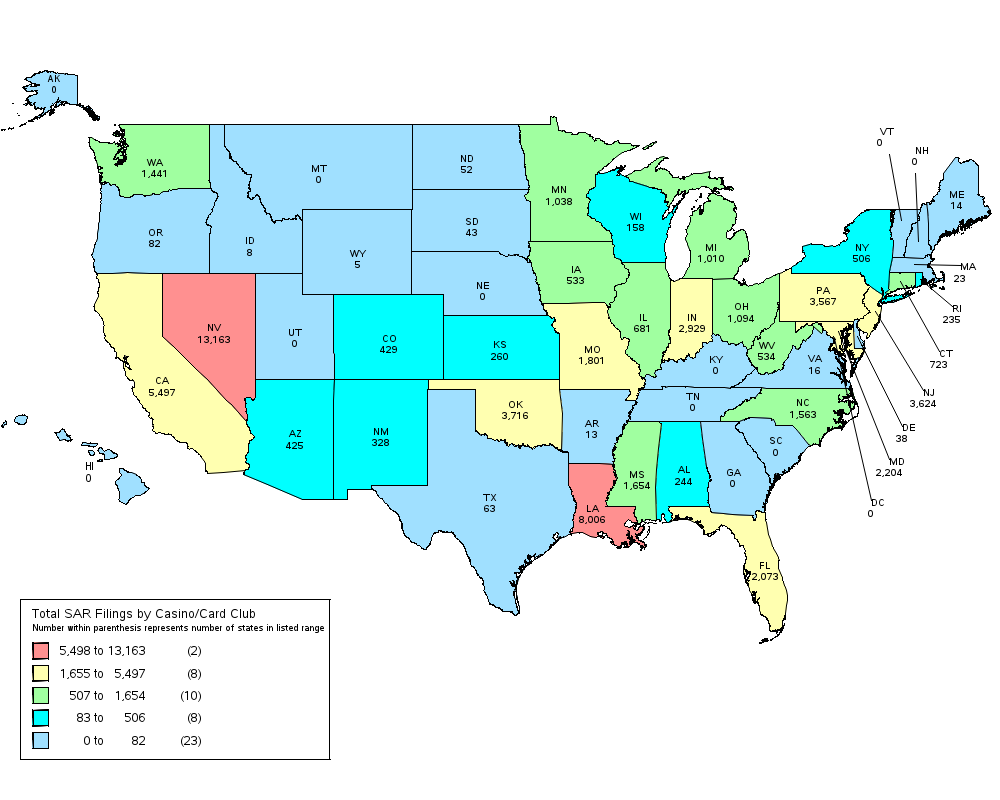

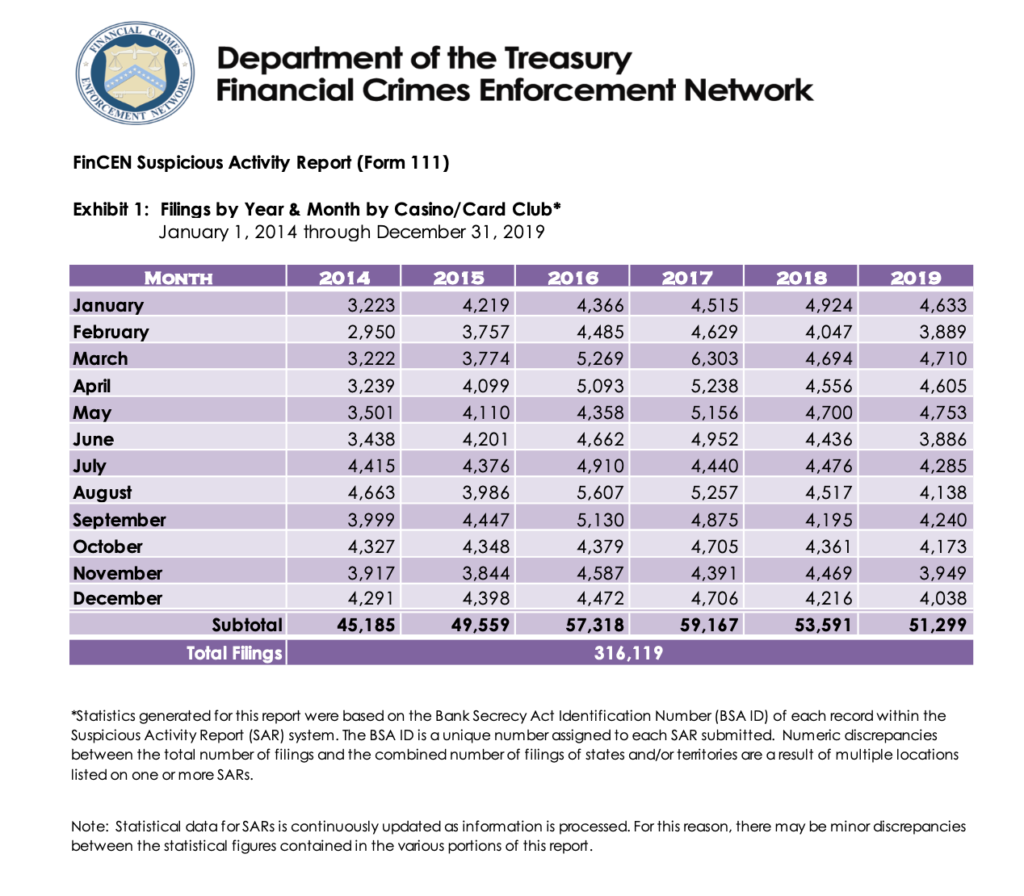

How does this stack up against previous years? According to FinCEN, between Jan. 1, 2014 and Dec. 31, 2019 — a six-year period — Casinos and Card Clubs in the United States filed 316,119 suspicious activity reports to the enforcement network. This included commercial and tribal casinos. Incidentally, in each of those years, except for 2015, which saw a December spike, the summer months appear to be high activity time for filing SARs in the gaming industry. The highest year in that period was 59,167 SARs filed in 2017, with March 2017 itself accounting for 6,303 SARs filed.

Just to give you an idea of how the gaming industry has upped the ante on filing SARs, in a seven-and-a-half-year period between Jan. 1, 2004, and June 30, 2011, according to a 2012 FinCEN report, “gaming institutions covered by FinCEN’s regulations submitted 74,816 Suspicious Activity Report by Casinos and Card Clubs (SAR-C) filings from 2004 through June 2011.”

Why Do Casinos File SARs?

In 1970, the United States Congress passed the Currency and Foreign Transactions Reporting Act, now called the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA), as the first laws to fight money laundering in the United States. It required financial institutions in the U.S. to help government agencies identify and prevent money laundering, with a specific focus on the recording and reporting of cash purchases of things like bank notes, checks, demand drafts etcetera (referred to as negotiable instruments) of more than $10,000, as a daily aggregate amount.

But Casinos Are Not Banks.

True, but they deal with financial transactions. Most casinos are considered non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs) under law. Essentially NBFIs are institutions that aren’t banks or don’t have a banking license but do offer financial services or conduct financial transactions.

According to the IRS, casinos and card clubs licensed to do business as casinos or card clubs by tribal, state or local governments, which have Gross Annual Gaming Revenues (GAGR) of more than $1,000,000 (annual means per year), are financial institutions subject to the requirements of the Bank Secrecy Act, which is codified in part in what is known as Title 31 of the United States Code (USC). Under this, certain financial institutions and individuals (defined by the Secretary of Treasury) are required to keep records and file reports on certain types of financial transactions. Which basically means they have to follow all reporting procedures under Title 31, or face the consequences of failure to report suspicious activity or a pattern of suspicious activity.

What Does The BSA Require?

The BSA requires that specified businesses, including those in the gaming industry, keep records and file reports that were determined to have a high degree of usefulness in criminal, tax, and regulatory matters. According to the IRS, “the documents filed by businesses under the BSA requirements are heavily used by law enforcement agencies, both domestic and international to identify, detect and deter money laundering whether it is in furtherance of a criminal enterprise, terrorism, tax evasion or other unlawful activity.”

Suspicious Activity Reports are required for suspicious activities involving $5,000 or more in funds or other assets (single transaction or aggregated). According to the IRS, casinos are also encouraged to report suspicious transactions that are under $5,000, such as the submission by a patron of an identification document the casino suspects is false or altered. If a currency transaction exceeds $10,000 and is suspicious, the institution must electronically file both Suspicious Activity Report (SAR), and Currency Transaction Report (CTR).

What Could Constitute A Suspicious Activity?

These are pretty well defined too. Some things that a patron could do that might be considered suspicious are (and this is not an exhaustive list):

- Exchanging many small bills for large ones

- Exchanging several monetary instruments, such as traveler’s checks, for one casino check

- Regularly conducting currency transactions that are just below $10,000

- Purchasing chips and then, after minimal gambling, redeeming the chips for a check

- Using other patrons to cash-out chips

- Supplying other patrons with cash to purchase chips

- Using the casino purely for its financial services

- Using identification that appears to be altered or forged

Note: The BSA is sometimes also referred to as an “anti-money laundering” law (“AML”) or jointly as “BSA/AML.” Several AML acts, including provisions in Title III of the USA PATRIOT Act of 2001, have been enacted up to the present to amend the BSA. (See 31 USC 5311-5330 and 31 CFR Chapter X [formerly 31 CFR Part 103]).