Police Use-Of-Force Data Collection: Too Little, Too Slow … But Could It Also Be Too Late?

In 2020, just 5,030 of 18,514 law enforcement agencies active in the United States that year provided use-of-force data to the FBI between January and August (we do not have data details as yet for the period post August). In 2019, that number was marginally higher — 5,043 federal, state, local, and tribal law enforcement agencies submitted use-of-force data. While the National Use-of-Force Data Collection is a very new program, kicking off on Jan. 1, 2019, one of the problems was that it took almost five years to get it off the ground, from ideation to reality. Right now, the program is completely voluntary — law enforcement agencies send incident reports to the FBI only if they choose to do so. Given the deep polarization and mistrust between law enforcement and some of the communities they serve in the U.S., it is imperative, however, for agencies to speed up the process of adoption, and move down the path of transparency and accountability.

By Kadambari M. Wade

Against the backdrop of the Derek Chauvin trial and a spate of other publicized incidents involving what appears to be an excessive use of force by law enforcement, one of the questions people naturally have is, how prevalent is the use of force among American law enforcement? Is the use of excessive force really as widespread an issue as news reports appear to indicate, or is that because particular incidents are highlighted by the media? Unfortunately, people’s answers appear to depend more on their political affiliations than the data itself.

So, what does the official data say? Regrettably, the answer is complicated. The short answer is that we don’t know — as yet. We do know, however, that we are a long way from getting to a national estimate when it comes to use-of-force data, simply because there isn’t enough participation from law enforcement agencies in the data collection process. In any case, the data, according to the FBI’s Trudy Ford, a section chief in the FBI’s Criminal Justice Information Services Division (CJIS), was “not meant to offer insight into a single incident, but rather a comprehensive view of the circumstances, subjects, and officers involved from a nationwide perspective.”

“Police-involved shootings and the use of force have long been topics of national discussion,” Ford told an episode of Inside The FBI last year, “but with recent high profile cases, it has heightened the public’s awareness of this topic. And so, we see this as an opportunity to report information that, from the law enforcement community’s perspective, makes sure that we’re accountable and transparent to the public while telling the entire story. And up until this point, there’s been a lack of data in order to share this from a national perspective.”

An FBI release in July 2020 had stated that in 2019, the inaugural year for which information collected from this use-of-force data was released, 5,043 federal, state, local, and tribal law enforcement agencies had submitted use-of-force data to the National Use-of-Force Data Collection. They said the agencies that submitted data between Jan. 1 and Dec. 31, 2019, represented 41% of all federal, state, local, and tribal sworn officers, which allowed them to release this first batch of information.

So, why is there so little official data on the use of force? As strange as it might sound, despite the United States’ long history of friction between an increasingly militarized law enforcement — there’s an excellent read by the conservative and libertarian think-tank, the Federalist Society, on this issue — and various communities dating back to the 1960s, the idea for collecting this data at an official level really only took root in 2015.

In June of that year (see below) it was recommended that the FBI create what would be a National Use-of-Force Data Collection, in the aftermath of a number of high-profile incidents involving the police. Here’s a timeline of events leading up to that July 2020 release.

Key Events in the Development of the National Use-of-Force Data Collection (FBI)

- June 3, 2015: The CJIS’s Advisory Policy Board (APB) recommended the FBI develop a new data collection on officer-involved shootings.

- Sept. 18, 2015: Representatives from major law enforcement organizations proposed an expansion to the FBI’s efforts, including uses of force that resulted in serious bodily injury.

- Dec. 3, 2015: The APB approved a new data collection on law enforcement use of force.

- Jan. 27, 2016: The National Use-of-Force Data Collection Task Force, including law enforcement leaders from across the U.S., met to discuss the collection.

- July 1, 2017: The data collection pilot study began. The FBI specifically invited law enforcement agencies with a workforce of 750 or more sworn officers to participate in the pilot study, and eventually, 98 agencies took part, including 24 that had a force of more than 750, plus 12 state UCR programs and three Department of Justice agencies. The study concluded on Dec. 31, 2017. On that day, which was the last day of the 6-month study, the average reporting rate of participating agencies was 70.5% for all agencies. The FBI followed up with reminder e-mails, phone calls, and pop-up notifications within the use-of-force portal to prompt agencies to complete their monthly submissions. Three weeks later, the average number of agencies submitting data, or zero reports increased to 89.9%.

- Sept. 5, 2018: The Office of Management and Budget gave final approval to begin collecting data.

- Jan. 1, 2019: The data collection launched nationwide. All law enforcement agencies were encouraged to participate.

- July 27, 2020: The FBI released participation data for National Use-of-Force Data Collection. Agencies reported this data either to their state’s Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) program, a designated UCR program for a particular organization (such as with federal agencies), or directly to the FBI.

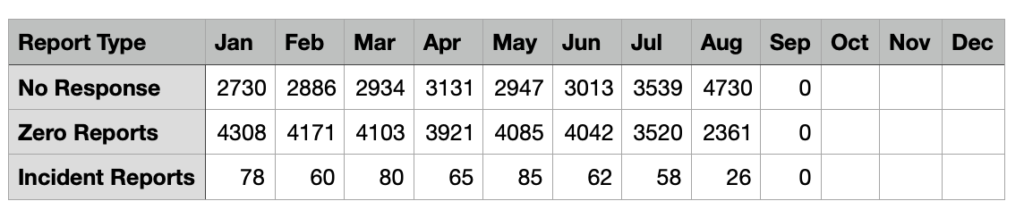

According to data from the Bureau’s Crime Data Explorer (CDE) for January through August 2020, 5,030 out of 18,514 federal, state, local, and tribal law enforcement agencies across the United States participated and provided use-of-force data. The officers employed by these agencies, according to the FBI, represented 42% federal, state, local, and tribal sworn officers in the nation. What is interesting, though, is if you look at how many reports were actually submitted in this Jan to August period, it doesn’t add up to all that much. There were 78 incident reports of use-of-force in January 2020, 60 in February, 80 in March, 65 in April, 85 in May, 62 in June, 58 in July, and 26 in August, for a total of 514 incidents.

How does that make 5,030 agencies reporting? Because from month to month, a number of agencies, and not necessarily the same ones, did report data, but said there were “zero reports” of incidents of use-of-force.

National Use-of-Force Data Collection: Number of federal, state, local, and tribal agencies providing incident reports, zero reports, or no response, January-August 2020.

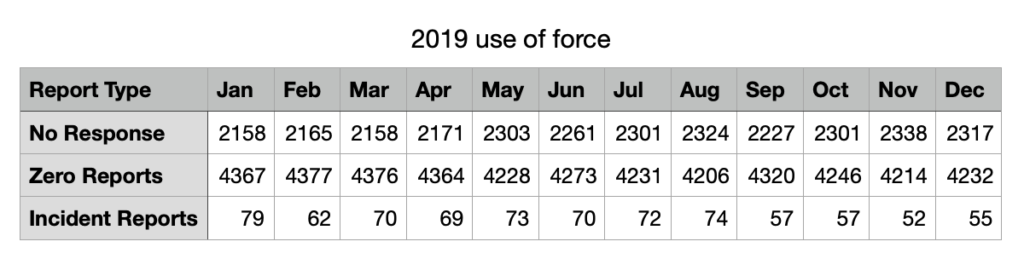

Here is a comparison with 2019 reports.

National Use-of-Force Data Collection: Number of federal, state, local, and tribal agencies providing incident reports, zero reports, or no response, January-December 2019.

When determining law enforcement participation in the National Use-of-Force Data Collection, the FBI uses a total count of 860,000 sworn police employees, as estimated by the Uniform Crime Reporting Program. This police employee count includes all known and reasonably presumed federal, local, state, tribal, and college and university sworn law enforcement personnel eligible to participate in the National Use-of-Force Data Collection.

According to the FBI, whether or not they publicly release use-of-force data from the Collection really depends on the percentage of agencies contributing data, and this is governed by federal regulations. Regardless of the level of use-of-force data reported, the FBI will periodically release information on agencies that participate in the data collection. The 2019 batch of initial data was therefore released when 40% of the total law enforcement officer population was reached. Additional data will be released at 60% and 80% participation levels.

Do note that while there isn’t comprehensive official data on the use of force, which would be needed to get an idea at the national level of whether there is or isn’t an excessive use of force by American law enforcement, or whether or not that force was warranted, there is comprehensive data on fatal police shootings, but from outside sources, like the Washington Post.

In 2015, in the aftermath of the 2014 Ferguson protests, following the fatal shooting of Michael Brown Jr., an 18-year-old black man, by a 28-year-old white police officer, Darren Wilson, in the St. Louis suburb of Ferguson, Missouri, the Post decided to log every fatal shooting in the line of duty by law enforcement.

Their rather incredible database contains records of every reported fatal shooting in the United States by a police officer in the line of duty since Jan. 1, 2015. It is updated regularly as fatal shootings are reported and as facts emerge about individual cases.

An awe-inspiring 12-month investigation by the Washington Post’s Kimberly Kindy and Kennedy Elliott, published on Dec. 26 of 2015, a year in which 990 people had been shot and killed by police up to that point, had some very fascinating takeaways. Do read the piece if you haven’t already, but here are a few insights from that report:

- In three-quarters of these fatal shootings, law enforcement officers were viewed as heroes — they had to take action either because they were under attack or were defending someone who was under attack. The Post found that 28% of individuals that died had been fatally shot while they themselves had been shooting at officers or someone else. In addition, 16% were shot while attacking people with other weapons or using physical force, and 31% were shot while pointing a gun at someone.

- Overall, the Post found that in 2015, 9% of shootings involved an unarmed victim, and these were disproportionately black. After adjusting for population, the investigation concluded that unarmed black men were seven times as likely as unarmed whites to die from police gunfire.

- Overall, more than half of those killed in 2015 had guns, 16% had knives and 5% tried to hit officers with vehicles. They stated that 3% had toy weapons, “typically replica guns that are indistinguishable from the real thing.”

- Worryingly, mental health issues played a role in one quarter of all the shootings.

- Equally worrying, perhaps, was the fact that only 6% of shootings were captured on body cameras, not exactly a resounding endorsement for transparency or accountability.

Despite the prominence given to gun deaths, the use of force, even the lethal use of force, is more than an incident involving firearms, as was seen in the case of Derek Chauvin’s knee on George Floyd’s neck for 9 minutes and 29 seconds.

So, what exactly is use of force?

A use-of-force incident occurs when a law enforcement officer takes an action that results in someone’s death or serious injury. Use of force incidents also include when a law enforcement officer fires a weapon at or in the direction of someone, even if that person isn’t seriously harmed or killed. Is it warranted?

As the Post investigation detailed above notes, in about 75% of cases of fatal shootings, they possibly were. While that was 2015, just in 2021, according to the Officer Down Memorial Page, 17 law enforcement officers have been shot dead in the line of duty, three have died after having been assaulted, two have been stabbed to death, and seven have been killed by vehicular assault.

Being a law enforcement officer in the United States is one of the most dangerous jobs around, not because of heavy machinery or falling trees, but because you go to work every day thinking someone may assault or kill you. As we had detailed in a separate report here, in 2019, 56,034 law enforcement officers were assaulted while performing their duties, according to assault data collected by the FBI from 9,457 law enforcement agencies that employed 475,848 officers. The year before that, 58,866 officers were assaulted while on duty, but that data was collected from a larger sample size: 11,788 law enforcement agencies that employed 546,247 officers.

The rate of officer assaults was higher in 2019 than in 2018, despite the smaller sample size. In 2019, the rate was 11.8 per 100 sworn officers, compared with 10.8 per 100 sworn officers for 2018. Nearly 80% of those assaults were done using personal weapons, i.e. hands, fists or feet, while 3.8% were done using firearms, 1.9% with knives or other cutting instruments, and 15.1% with other dangerous weapons.

Of all the officers who were assaulted in 2019, 30.4% were responding to disturbance calls, including family quarrels or bar fights, while 17.1% were attempting other arrests, and 12.8% were handling, transporting, or maintaining custody of prisoners. This data was based on data from the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Program on LEOKA (Law Enforcement Officers Killed and Assaulted) for 2019. It focuses just on officers who died because of injuries received on duty in felonious incidents, not accidental ones.

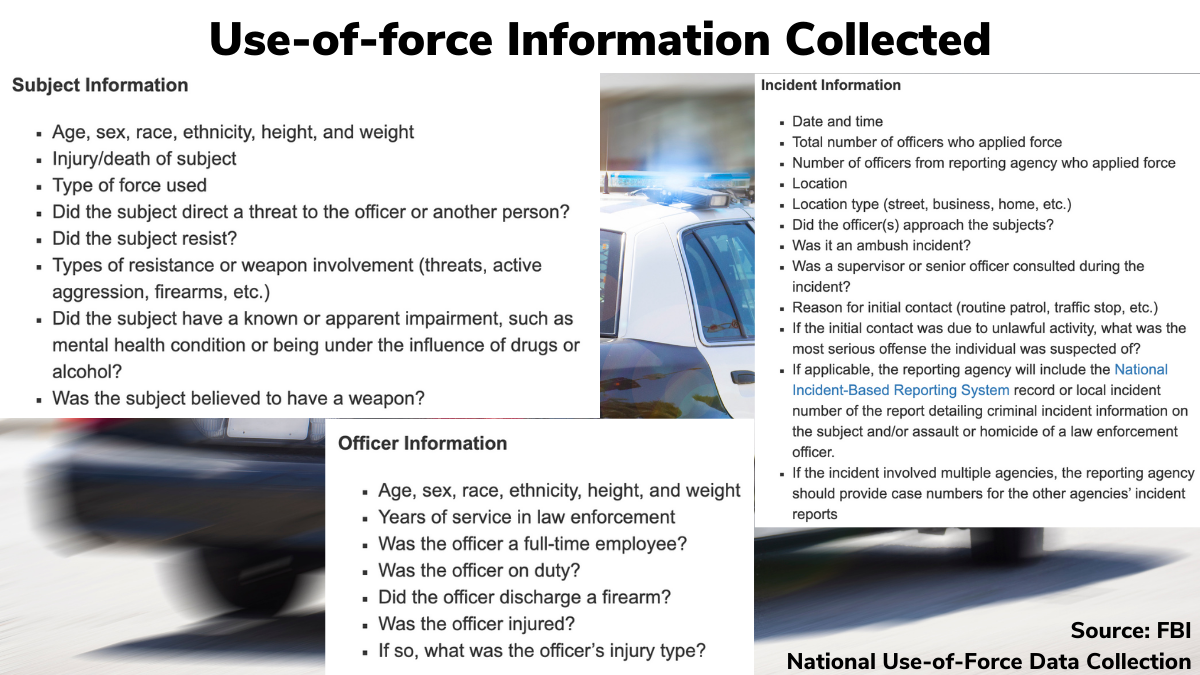

What data is collected for the use-of-force collection?

The collection and reporting of data includes any use of force that results in:

- The death of a person due to law enforcement use of force.

- The serious bodily injury of a person due to law enforcement use of force.

- The discharge of a firearm by law enforcement at or in the direction of a person not otherwise resulting in death or serious bodily injury.

For the purpose of this data collection, the definition of serious bodily injury is based in part on Chapter 18 United States Code Section 2246 (4). The term “‘serious bodily injury’ means bodily injury that involves a substantial risk of death, unconsciousness, protracted and obvious disfigurement, or protracted loss or impairment of the function of a bodily member, organ, or mental faculty.” If agencies experience no qualifying use-of-force incidents within a month, they submit a zero report.