Black And Indigenous People Are More Likely To Be Killed In Traffic Accidents Than Other Racial Groups

By Aara Ramesh

On Tuesday, June 22, the Governors Highway Safety Association (GHSA) released a report showing that Black and Indigenous people are disproportionately dying in traffic accidents, according to an analysis of federal data. This comes on the heels of a different report published earlier this month by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), which found that U.S. traffic deaths in 2020 rose 7.2% to 38,680 (compared to 2019), despite the fact that lockdowns meant that Americans drove 13% fewer miles last year.

The GHSA, a non-profit that works with highway safety offices, said that its latest report is the first comprehensive analysis on the subject of racial disparities in traffic fatalities in more than a decade. In the course of the study, the group looked at data from the National Center for Health Statistics and Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS) from 2015 to 2019 with the aim of understanding racism in enforcement and racial equity in safety when it comes to traffic accidents.

According to the GHSA, what it found is a “significant health disparity” and “a chronic public health issue in minority communities.”

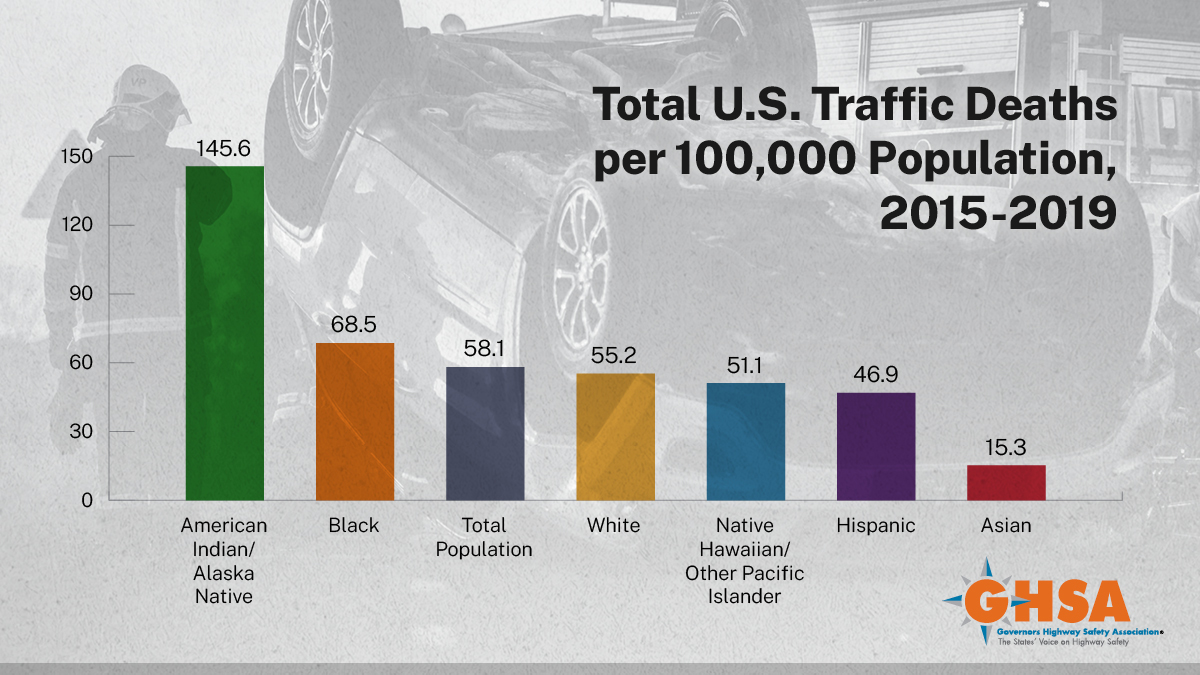

Per the report, American Indian/Alaskan Native populations had a substantially higher per-capita rate of traffic fatalities (including total, pedestrian, and bicyclist deaths), compared to other racial groups, with Black persons coming in second. Excluding the motorcycle driver deaths and passenger deaths categories, white people were found to have generally lower traffic fatality deaths than Black, Indigenous, and other People of Color (BIPOC).

The national average is 58.1 traffic fatalities per 100,000 people. When broken down by race and ethnicity, the disparity is even more stark. For Native Americans and Alaskan Natives, the rate is 145.6. For Black people, it is 68.5.

According to the latest figures from the NHTSA, pedestrian deaths among Black people skyrocketed 23% in 2020, the highest of any of the racial groups. The figure jumped by 11% among American Indians. Between 2005 and 2019, the gap between overall traffic deaths among Black and white people widened, jumping 16% for the former and dropping by 27.8%.

According to Smart Growth America, over the last decade, the overall, nationwide number of people hit and killed by drivers increased 45%. The rate of Black people being hit and killed was 82% and was an eye-watering 221% for American Indian and Alaskan Native people, as compared to white, non-Hispanic Americans.

Though traffic infrastructure, road planning and design, vehicle safety, and awareness have improved greatly since the 1970s, many believe that low-income communities have been left behind.

Urban planning and transportation experts have pointed to a number of factors that could explain why BIPOC are overrepresented in traffic fatality figures. For instance, Black people are more likely to live in cities, which — the NHTSA has noted — suffer higher rates of traffic accidents than rural areas.

Within cities, low-income areas have traditionally received less investment in roadway infrastructure, traffic enforcement, community engagement, and traffic safety education. They tend to have fewer functional traffic lights, crosswalks, and warning signs; and are more likely to have uneven roads and sidewalks, and more ongoing construction, etc., all of which seriously impact road safety. These low-income areas are largely (though not exclusively) populated by BIPOC

The national initiative to improve the Interstate Highway System half a century ago ensured that busy thoroughfares were built predominantly through low-income neighborhoods. The high-speed nature of these highways makes it more dangerous for those who live in these areas.

Experts also say that BIPOC people may not be able to afford vehicles and so are overrepresented among pedestrians. Smart Growth America found that people walking in lower-income neighborhoods are killed far more often than those in richer areas. In its early June report the NHTSA said that in 2020 drivers had displayed a greater propensity for risky behavior like speeding, due to the roads being empty as a result of the lockdowns.

Further, there are suggestions that the high pedestrian deaths figures are an indication of the fact that BIPOC communities, particularly Black people, were disproportionately represented among essential workers and could less afford to stay at home or work from home during the lockdowns.

Looking at it even more broadly, public health infrastructure and access to medical care tends to be of poorer quality in low-income neighborhoods. According to the GHSA, this means that though the severity of accidents may be comparable across different socioeconomic areas, the outcomes of these crashes can vary significantly and be more deadly for poor people, as a result of slower response times and the inadequate medical care available.

It is not easy to detangle this racial disparity in fatality statistics without looking at the underlying problems that disproportionately affect BIPOC people, especially socioeconomic status, which has implications for where people live, where they work, how they get to work, and how much has been invested in their neighborhoods.

The various organizations and agencies working to improve road safety have suggested a number of actionable solutions. They include:

- Treating disparities from traffic fatalities as a public health issue.

- Enhancing infrastructure investment and safety planning initiatives in underserved/poorer areas.

- Implementing best practices and lessons learned from confronting other racialized challenges (like mental health and poverty) in traffic safety measures.

- Investing in R&D to develop capabilities to predict and prevent traffic accidents.

- Working with local organizations and BIPOC leaders to design more effective, customised safety education campaigns.

Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg responded to these statistics by saying, “Last year’s traffic fatality rates and the racial disparities reflected in them are unacceptable. This reflects broader patterns of inequity in our country — and it underscores the urgent work we must undertake as a nation to make our roads safer for every American.” He highlighted that President Joe Biden’s stalled American Jobs Plan earmarks $20 billion for road safety initiatives, half of which will go to making streets safer and reducing accidents.