Like The Rest Of The World, Terror Groups Moved Online In 2020: Europol

By Deepti Govind

Despite the Covid-19 pandemic leading to travel bans and restrictions world over in 2020, a new Europol report shows that in the European Union (EU), at least, terrorists were still very much active during the year. Like the rest of the world, all they did was switch most of their communication and planning to online channels from offline.

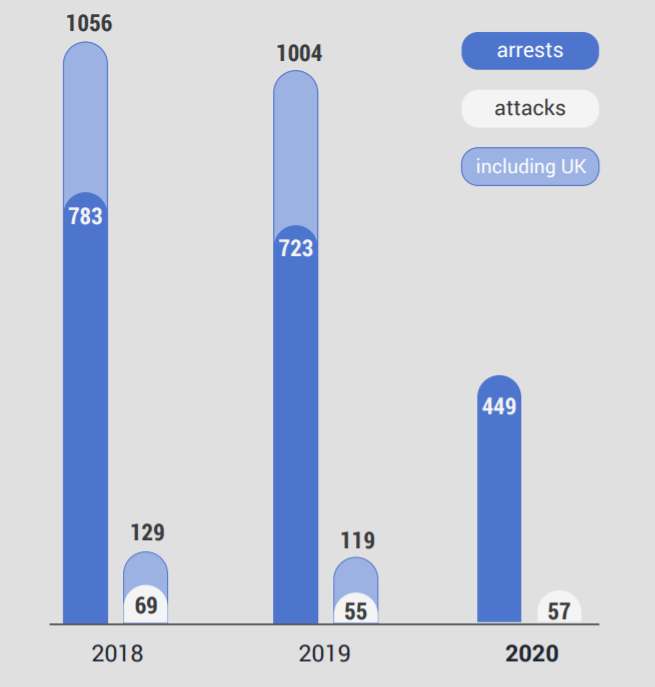

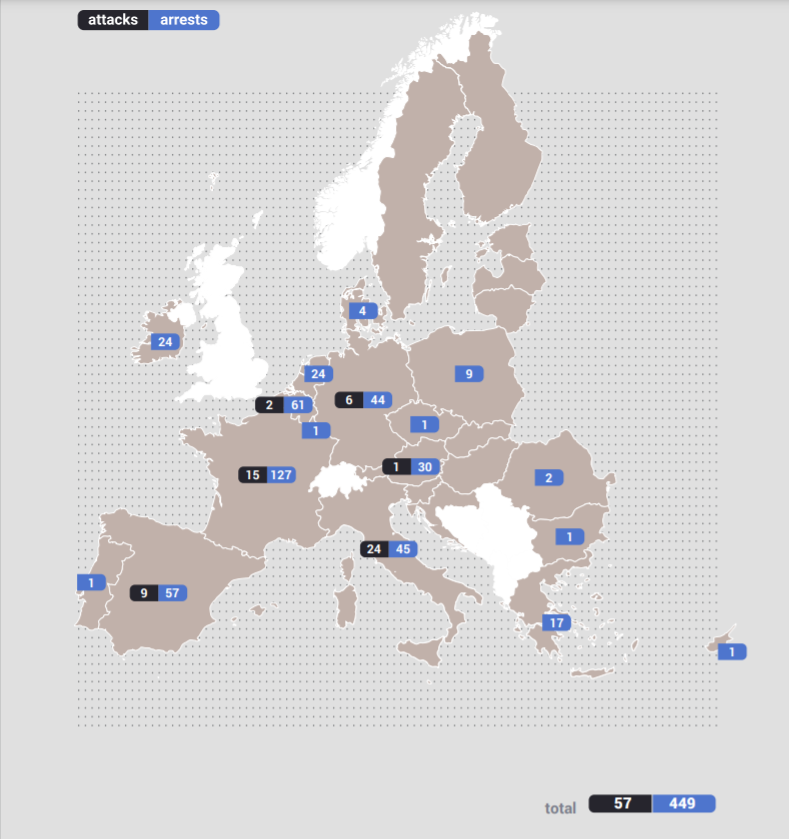

The number of attacks, though, appear to have stayed largely stable compared with previous years. In total, EU Member States reported 57 attacks in 2020, while the UK reported 62 such incidents and Switzerland reported two. That number (121) is higher than 2019’s combined total of 119, but lower than 2018’s total of 129 incidents.

In the EU, 21 people died as a result of terrorist attacks and at least 54 people were injured in 2020. The deaths were the result of one right-wing terrorist attack (in which nine people were killed) and six jihadist terrorist attacks (during which 12 people were killed). In the UK, three people lost their lives in a jihadist-inspired terrorist attack. One person died in the attacks in Switzerland. With the exception of the targeted assassination of a school teacher on 16 October 2020 in France, the victims in these terrorist attacks appear to have been selected at random, as perceived representatives of populations that the perpetrators intended to harm on ideological grounds, the report says.

In total, 449 individuals were arrested on suspicion of terrorism-related offences in the EU, while 185 were arrested in the UK. The number of terrorism-related arrests in 2020 was significantly lower than in previous years. This decrease, however, is not necessarily linked to decreased terrorist activities. The UK, in fact, cautioned that the decline in terrorism-related arrests and convictions can also be attributed to the operational changes necessary under the government restrictions imposed in March 2020 because of the pandemic.

The number of completed jihadist attacks in Europe (EU, Switzerland, and the UK) in 2020 more than doubled in comparison with the number in the EU (including the UK) in 2019. However, it’s not immediately clear if that jump is linked to the effects of the pandemic, the report said. Another important point to note is that all completed jihadist terrorist attacks were carried out by lone actors, while disrupted plots mainly involved multiple suspects. Lone attacks were also incited by the jihadist terror group Islamic State (IS) and the al-Qaeda network. Except for the attack in Vienna, in which firearms were used, the modi operandi typically involved rudimentary methods (stabbing, vehicle ramming, and arson).

What’s both interesting and alarming is that the pandemic did not fundamentally modify terrorists’ core modi operandi, but there was one shift that the report repeatedly stressed: Much of the communication among terror groups appears to have shifted online due to the pandemic. Europol’s comprehensive 113-page report covers various aspects of terror group activity during the year of the pandemic. But in today’s piece, we examine in detail just the overall impact of the pandemic on terrorism and extremism per the report.

First, how does the EU define terrorism?

Terrorist offenses are certain intentional acts, which, given their nature or context, may seriously damage a country or an international organization when committed with the aim of:

- seriously intimidating a population;

- unduly compelling a government or international organization to perform or abstain from performing any act; or

- seriously destabilizing or destroying the fundamental political, constitutional, economic, or social structures of a country or an international organization.

That is the definition according to EU Directive 2017/541 on combating terrorism, which all EU Member States were obliged to transpose into their respective national legislation by 8 September 2018.

Covid-19 And Terrorism In Europe

To begin with, terrorists and extremists of several different ideological persuasions tried to mold the pandemic into their own longstanding narratives. For instance, IS said the pandemic was a punishment from God for his enemies, inciting the group’s followers to perpetrate attacks to take advantage of the increased vulnerability of anti-IS coalition countries.

“Al-Qaeda interpreted the spread of the pandemic in Muslim-majority countries as a sign that people had abandoned true Islam, and appealed to Muslims to seek God’s mercy by liberating Muslim prisoners, providing for people in need, and supporting jihadist groups. Both IS and al-Qaeda pointed to the withdrawal of Western troops as an opportunity. Right-wing extremists exploited Covid-19 to support their narratives of accelerationism and conspiracy theories featuring anti-Semitism, and anti-immigration and anti-Islam rhetoric. Left-wing and anarchist extremists also incorporated criticism of government measures to combat the pandemic into their narratives,” the report says.

Of course, the most important question on everyone’s minds is whether terror groups tried to use the Covid-19 virus as a bioweapon. Thankfully, Europol says no such attempts were reported in the EU. Although some people have discussed weaponizing the virus, most often technical information does not have the appropriate scientific background, it says. Ways of using it indirectly were discussed among terror groups, including methods like close contact, airborne or fomite transmission, shipping of contaminated products, and even distributing poisoned masks to the public on the streets.

EU Member States voiced concern about possible security-related effects of the pandemic for several reasons, some of which were:

- A risk that the situation created by the pandemic could be an additional stress factor for radicalized individuals with mental health issues.

- That, in turn, could cause lone actors to turn to violence sooner than they would have otherwise done.

- Specifically, certain aspects of the pandemic could, by itself, contribute to self-radicalization. Those include factors like social isolation from family and peers, fear of falling ill, increased time spent online or at home with radicalizing influences, reduced job security and subsequent financial difficulties, dissatisfaction with the measures to stop the spread of the pandemic, and misinformation online, especially on social media platforms.

- While movement and travel restrictions due to the pandemic probably ended up becoming a self-radicalization factor, it also meant reduced chances for intervention with individuals having fewer points of contact with government bodies in areas such as education, healthcare, social welfare, and law enforcement.

- Another fallout of the pandemic and its ensuing social and economic crises has been the polarization of society. Attitudes have hardened and there’s a general increase in acceptance of intimidation, including calls to commit violent acts. Expressions of social dissatisfaction increased, both online and offline, with social media playing a facilitating and mobilizing role, as well as the proliferation of disinformation and conspiracy theories.

- The polarized climate, in turn, has created opportunities for extremist groups to reach audiences beyond their traditional supporter circles.

Online Propaganda Is An Increasing Worry

Not only did many terror and extremist groups move their workstations online, they also tried to take advantage of the fact that the rest of us have also been spending an increased amount of time online during the pandemic. With a large amount of disinformation actively disseminated online, extremists and terrorists have exploited social dissatisfaction to reach out and propagate their ideologies. Virtual communities have become increasingly prominent in the dissemination of extremist and terrorist propaganda.

Since the Telegram takedown in late 2019, for instance, jihadists have been struggling to find new dissemination channels, the report says. As a result, jihadist propaganda has become dispersed across a variety of platforms. Online communities are playing an increased role in the propagation of right-wing extremism. In recent years, such communities have coalesced around white supremacist or neo-Nazi views and shared language.

Take the example of a man who was active in anti-government and conspiracy theorist circles online and who was arrested in the Netherlands in early June 2020. He was a leading figure in an online group with 12,500 followers on Facebook and was also active in various Telegram groups. In statements probably targeting the measures to combat Covid-19, he allegedly referred to the need for “citizens’ arrests” of Members of Parliament and staff working at the Dutch Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu (RIVM, National Institute for Public Health and the Environment).

Violent acts by individuals opposed to the Dutch government’s anti-Covid-19 policies included attacks on a city hall with stones and fireworks, daubing of Covid-19 testing locations, and intimidation of personnel. Threats to journalists also increased. In Poland, extremist circles employed new recruitment strategies that involved enhancing their popularity among social groups that are not typically interested in their ideology.

Right-wing propaganda is mainly disseminated online and gaming platforms have been increasingly used for spreading extremist and terrorist narratives, Europol said. Suspects linked to online communities with different degrees of organization are also increasingly younger, some are just minors at the time of arrest. The attacker who killed nine people in February 2020 in Hanau, Germany was motivated by xenophobic and racist ideology. He had his own website, which he used to propagate his de-humanizing views, Europol says.

“The latest report from Europol on the EU terrorism situation illustrates that in the year of the COVID pandemic, the risk of online radicalisation has increased. This is particularly true for right-wing terrorism. I discussed this trend in Lisbon today (22 June) with US Secretary for Homeland Security Alejandro Mayorkas at the EU-US JHA. We are committed to tackling this growing threat,” Ylva Johansson, European Commissioner for Home Affairs said in a statement.

There were also arson attacks on telecommunication towers in various European countries linked to Covid-19, the report adds. Conspiracy theories suggesting a connection between Covid-19 and the roll-out of 5G technology were the origin of these extremist incidents. In the Netherlands, 30 telecom towers were set alight from April 2020. Seven suspects were arrested, but no link seemed to exist between the various incidents of arson, and there were no indications of any common organization, coordination, leadership, or even an overarching ideological motivation. The incidents seemed to be fueled by conspiracy theories, but some may also have been carried out by copycats, inspired by previous incidents of arson and the media coverage they received.

“The online domain plays a crucial role in enabling the spread of terrorist and extremist propaganda. In a world that has become considerably more digital, targeting the propagation of hatred and violent ideologies spread online is an imperative. By sharing information in real time and using the latest technological advances within a strong data protection framework, we can further enhance the way we fight terrorism together. Ultimately, law enforcement’s main goal is to target violent extremism and radicalisation to save lives and minimise the violent attacks against our society and our democratic system,” Catherine De Bolle, Executive Director of Europol said.

Given the comprehensive nature of the Europol report, this is the first in a series of pieces we will be doing based on its findings.