‘We Do Not Know How Many Children Around The World Go Missing … The Data Doesn’t Exist’

Above: A young child, evidently alone, and at risk, asks for a lift by the side of a road as the sun begins to set. © Alien185 | Dreamstime.com

Note: This is the second in a series of “Conversations across Communities,” which will touch upon various aspects of security, surveillance, law enforcement, intelligence, crime, crime prevention, criminal behavior, law, investigations, research, technology, demographics, data, incarceration, and the effect and confluence of business, government, non-government and policy work on these. It features the people and communities affected by changes in and across these areas. Each conversation will be highlighted in Biometrica’s monthly newsletter on the first Wednesday of every month. You can sign up for the newsletter here.

By Kadambari M. Wade

ICMEC, the U.S.-based International Centre for Missing & Exploited Children, was formed in 1999 to lead and coordinate a global effort to eradicate child abduction, sexual abuse and exploitation. Caroline Humer, the Director of ICMEC’s Global Missing Children’s Center, is at the forefront of their effort to continue to grow their global resource network, and use technology, including machine learning and facial recognition, to empower law enforcement and other first responders around the world to find missing children and their abductors.

An impassioned advocate for using technology for the good, Ms. Humer spoke to us about some of the major challenges on the frontlines of the battle to prevent children going missing, and to prevent them becoming victims, the paucity of data on missing children, the upcoming GMCNgine, using Amazon’s Rekognition, and much more.

What exactly is a missing child?

Caroline Humer: While there is no universally-accepted definition of a “missing child,” at ICMEC we use the definition of “any child under the age of 18 whose whereabouts are unknown.” Consistent with the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, a child is anyone under the age of 18.

When is a child considered missing?

It varies from country to country and jurisdiction to jurisdiction. In my opinion, a child is missing as soon as you do not know where he or she is, or where he or she is supposed to be. There is no defined period of time for how long a child must be gone before you can call them a missing child.

It can be the 10 seconds you lose sight of your child at a playground or a supermarket, or it can be the 10 hours your child hasn’t come home from school, but you didn’t know that your child was missing because you thought your child was at school or school-related activities.

The amount of time doesn’t matter; it’s your thinking, and you have to act immediately.

So there’s no question of overreacting?

Correct. When you think your child is missing, report it immediately, don’t wait 24 hours, don’t wait two hours. Law enforcement should take the report immediately, should start an investigation immediately.

A missing child is a vulnerable child.

Information the intake officer should take from a person reporting a missing child.

Note: This is not an exhaustive list.

• Full Name of child, age, height, weight, eye and hair color, any characteristic description.

• What was the child wearing, the last time he/she was seen?

• Where was the child last seen?

• Does the child have any medical condition?

• Does the child have means of travel — i.e., money, credit card, etc.?

• Does the child have an online presence or a cellphone?

• A list of the child’s friends, and any clubs they belong to.

• A recent photo of the child

• Any witness or car involved

• The full name and contact information of the reporting person and their relationship to child

Is there a difference in the way law enforcement treats missing children reports below a certain age or above a certain age in the below-18 category, say, below-12 or above-14?

It really depends on the country. However, what we teach law enforcement during our training programs across the world is that you have to treat every missing child as if that child is in danger, no matter the age. Every case is different and that’s the difficulty and the complexity of these cases. Law enforcement has to assume a child is at risk until there is information that proves otherwise.

One of the problems we’ve talked about is the fact that there is no universal definition of “missing” children, and that complicates everything.

If you don’t know how to define it, how are you going to respond? If you don’t know what you’re dealing with, and can’t describe it, you can’t know what resources you need, or what to do. So, the first thing we do when we work with law enforcement is teach them what missing means, so they can respond accordingly — is it, for instance, a runaway, a parental abduction or a stranger abduction? Those are very different kinds of responses, but they’re all missing kids with different inherent risks. By defining it, you actually acknowledge the issue and a problem that needs to be addressed.

If there’s no universal definition, there’s no basis for comparative analysis of data. We know there’s not enough data for a variety of reasons. But when there’s no universal definition of missing children, is a missing child in Australia or India or Canada a missing child in the United States? If not, why? Could you elaborate?

Absolutely. When data is available, it’s being collected differently because definitions differ. Different agencies even within the same jurisdiction may define the same categories differently or collect data differently. A runaway may be called something different in one jurisdiction and something else in another. That makes it hard to compare the data — how many cases are reported, how many are solved, etcetera. That’s why we don’t know how many children around the world go missing annually.

Just as an example from here in the United States, approximately 465,000 reports of missing children are entered into the FBI’s National Crime Information Center (NCIC) database, on an annual basis. It is important to note that these numbers are reports of missing children. So, a child who runs away multiple times would be counted each time he or she was reported as having run away.

So those 465,000 cases are not individual records, they’re incidents?

They’re reports of individual incidents and not the number of children who go missing. For example, within that 465,000, you’ve got children who have run away multiple times, which means the number of missing children in the United States is different from the number of reports of missing children.

At the end of 2017, the NCIC “Missing Persons File” contained more than 32,000 records of youngsters under the age of 18. Could you explain that number?

That means that at the end of 2017, 32,000 reports of missing children were still open. But overall, in 2017, there were 465,000 incidents that were reported. A majority of those cases (93.12%) have been closed because the child has been found.

Would the 32,000 open cases still include duplicate records — not in terms of incidents, but in terms of children that have been counted twice for various reasons?

Yes. For instance, by law, in the U.S., care homes have to report every missing child to law enforcement. You’ve got children who run away from care homes multiple times a day, or every other day. Those 32,000 will include duplicates because they’re incidents, not the number of children. It’s important to note, however, that these are not necessarily “inflated” numbers, given recidivism — repeat runaways, for example — and also because there are people that do not report their child as missing. We simply do not know how many people do not report their children as missing, but we know they are there.

So we have no way of knowing how many children are missing?

It comes back to if we don’t define it, we don’t know and we don’t collect it. A lot of countries don’t look at the issue because once they open Pandora’s Box, they fear it will be bigger than they can handle. They don’t want to look at it.

There are obviously different challenges in dealing with different countries. With migration, for instance, how hard are some of the challenges of inter-country parental or familial abductions? How are they treated?

There are challenges, and they are complex and difficult. One of the issues we constantly face is building awareness and understanding around the issue. We look for a leader or champion within that country, look to understand the challenges there, and understand how to solve the challenges particular to that country or region. There is a process that focuses on defining, educating, building awareness and being able to know what it is. For instance, with parental abductions; in some countries they’re considered a civil matter, in others, a criminal matter. This determines the response by law enforcement and the country. What we look for is having a coordinated response on the ground from the leader we’ve identified.

Could you elaborate?

We know that with children who are missing, whether a parent or someone else abducts them, they’re running to or away from something, and we have to address these issues as well. “Missing” is a gateway to a host of risk factors. By focusing our attention on the prevention of and quick response to missing children, we are working to get to a child before he or she is victimized. Every case is different, every country is different, but certain things are the same — a child who is missing is a vulnerable child in need of protection, no matter the circumstances under which he or she went missing.

At what point does a missing child become a victim?

As soon as they leave their safe environment, a missing child may become a victim. However, children could also be victims in their own homes, and in many cases this may be a reason a child goes missing. We stress upon law enforcement the importance of making sure the environment is safe, before returning a child who has been found after going missing.

[Note: Here’s a link this to a piece on online grooming we’d carried last year from Sandra Marchenko, Director of The Koons Family Institute on International Law & Policy at ICMEC].

Technology For The Good

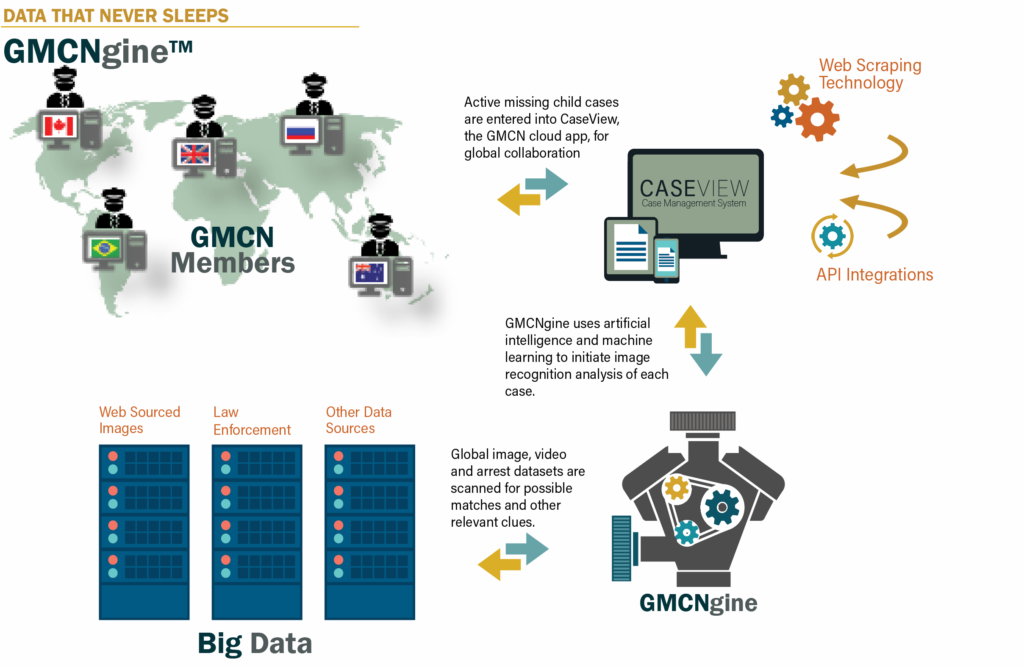

Above: A representation of how the GMCNgine will function, courtesy ICMEC and the Global Missing Children’s Center. The GMCNgine is an innovative new image-based search and matching platform, which will use machine learning, facial recognition and access to multi-jurisdictional criminal databases to scour the surface web and the dark web for leads on missing children and their abductors. It will be accessible to law enforcement and other first responder members of the GMCN.

Technology is obviously one major focus of ICMEC, as is the new Facial Recognition initiative you’ve been working on with Amazon Web Services and Amazon Rekognition, among other security services. Is there anything you can share with us about your plans on the technology front, to help find missing children through a global facial recognition database?

We’ve been working with AWS and other security and data companies like yourselves [Biometrica], to create one single global platform that allows law enforcement and NGOs that are members of our Global Missing Children’s Network to upload an image of a missing child into the database and then use AWS facial recognition to search for that missing child and have leads return to them on the possible whereabouts of that missing child.

In your case, with Biometrica, we’d be looking at possible leads being returned on the abductor’s information. This platform, that we call the GMCNgine would then allow law enforcement and NGOs to use technology to find missing children, either directly, or by finding the person they are with.

What do first responders use at the moment, for the most, while looking for missing children?

Generally speaking, they’re using old-fashioned methods to finding missing children — they’re creating a poster, putting it on a lamp post, putting it on Facebook, putting it on a website, or a bus, or in a taxi or a gas station. Those are great, however, they’re limited in both reach and capacity, because you’re only focusing on the people that come across it in person, either in the physical realm or the virtual. What we’re hoping to do is move them into a different era, technologically speaking, and use technology to scour the Internet to find missing children.

We’ll be able to find these children anywhere on the web using Amazon, if the child posts a picture of themselves, or with another person, or if someone posts a picture of the child, we can have law enforcement run that picture of the abductor through your database to look for possible leads on the whereabouts of the abductor, and therefore, through that abductor, get the whereabouts of the child.

When do you hope to kick off the GMCNgine?

Later this year.

I have a data question. We have some data from different countries; do we have data at all on children that are missing in Central America?

We don’t have data on all children missing in/from Central America, but we do work with countries in Central America and they’re doing great work. They have a huge challenge that they are dealing with and they’re dealing with it the best that they can. We are working with Central American countries to put in place an appropriate and coordinated response on missing children and that follows our Model Missing Child Framework.

Above: The Global Missing Children’s Network (GMCN) country members.

Could you elaborate on the response they’re looking to put in place?

Guatemala is doing great work putting procedures in place to find missing children, they’ve got laws in place, they’ve also got a risk assessment in place that allows them to determine what the risk is to a child that is reported missing. We worked with Costa Rica to implement some of their Model Missing Child Framework implementation, and also with Panama and El Salvador.

We’re also working with other countries throughout Latin America. For example, Mexico has an AMBER Alert program in place that the United States helped implement. Colombia is in the process of developing their AMBER Alert program, and Ecuador is launching their alert this June. There’s a lot happening in the region.

[Note: Ecuador’s Ministry of the Interior announced the country’s AMBER Alert program, called Alert Emilia, along with the announcement of their tie-up with ICMEC in January 2018. They named their warning system after 9-year-old Emilia Benavides, who was abducted and murdered in 2017].

About the International Centre for Missing & Exploited Children (ICMEC)

ICMEC works around the world to advance child protection and safeguard children from abduction, sexual abuse and exploitation. Headquartered in Alexandria, Virginia, ICMEC also has regional representation in Brazil and Singapore. Together with an extensive network of public and private sector partners, ICMEC’s team responds to global issues with tailored local solutions.

(You can reach the writer at kmurali@biometrica.com)