When Terror Comes Calling: Safety, Security & Survival In The Age Of Mass Casualty Attacks

By Kadambari M. Wade

On Oct. 1, 2017, Stephen Paddock opened fire on the Route 91 Harvest Music Festival from the 32nd Floor of the Mandalay Bay Hotel. One nondescript killer, a man who fit no known profile of a mass murderer, prior to or since the events of that fateful evening, managed, in the space of minutes, to let off more than 1,100 rounds of gunfire.

It was enough to kill 58 people and cause physical injuries and unknown, irreparable harm to 869 others. There were 413 gunshot or shrapnel injury victims, 360 people sustained injuries other than from gunshot or shrapnel, and 96 were identified as “having sustained other injuries where the type of injury sustained was unable to be confirmed,” in the Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department’s final “Criminal Investigative Report of the 1 October Mass Casualty Shooting.”

One year since that eventful night, life has moved on in Vegas, except for the survivors and victims’ families. It remains a people magnet, glitzy and glamorous, shimmering in the desert heat, even if every now and then, despite the Golden Knights’ season in the sun, there is now a frail reality to that shimmer, something familiar to the citizens of any city that has been brutalized; a tarnish to that shining city in the valley that has nothing to do with the underlying tawdriness that has always been the flip side of the lights of Las Vegas, a veiled viciousness that, to locals, was always an accepted part of life in Sin City, or any city of temptation.

Locals understand that this callousness of Vegas is also part of her siren’s call, but for many of them, October 1 last year was a different kind of ugliness, one that ripped the bandage off gaping wounds. Over this past year, through innumerable calls for strength and endurance and resilience, there have also been calls for shoring up the city’s defenses, and for stronger security, both on the law enforcement side and from the businesses and industries that depend on Vegas’s massive influx of everyday tourists for their very survival.

There is also a belief, however, that this is a city that has seen a heck of a lot through the years and decades, and she has always fought back, stronger, and she has always shimmered on under the unforgiving Nevada sun.

In this final piece of our MUPC month series, on this one-year anniversary of Paddock’s pitiless assault, we asked Jeffrey Muller to take us through the Investigation of Mass Casualty Incidents and Terrorism. Mr. Muller, now the president of strategic security group Muller Group International (MGI), is perhaps uniquely qualified to answer these questions. The son of a lifelong FBI agent and an FBI victim witness coordinator himself, he understands the importance of the investigator’s perspective as much as keeping victims and survivors front and center. He and his brother, a helicopter pilot with the U.S. Army, grew up all over the country, but he considers Maryland home, having finished high school there and gone on to the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis.

He’s been on SWAT Teams, in war zones — during Desert Storm — is a trained sniper, was a weapons and engineering officer in the United States Navy, and served 21 years as a Supervisory Special Agent in the FBI, where he co-founded the Bureau’s Weapons of Mass Destruction Directorate. He also developed and founded INTERPOL’s Chemical, Biological, Radiological, Nuclear and Explosives (CBRNE) Directorate in Lyon, France, and chaired the United Nations Critical Infrastructure Protection, Tourism Security and Cybersecurity Working Group, comprised of 34 UN agencies.

Jeff Muller: One year ago, on October 1, 2017, 64-year-old Stephen Paddock, who had had no prior engagement with law enforcement other than a few speeding tickets, and had no evident ideological or other motive that could be determined, acted alone, 100% — we know this from thousands of hours of interviews as his moments were detailed down to the second, going back months and years; committed one of the worst mass murders and one of the greatest mysteries of our times.

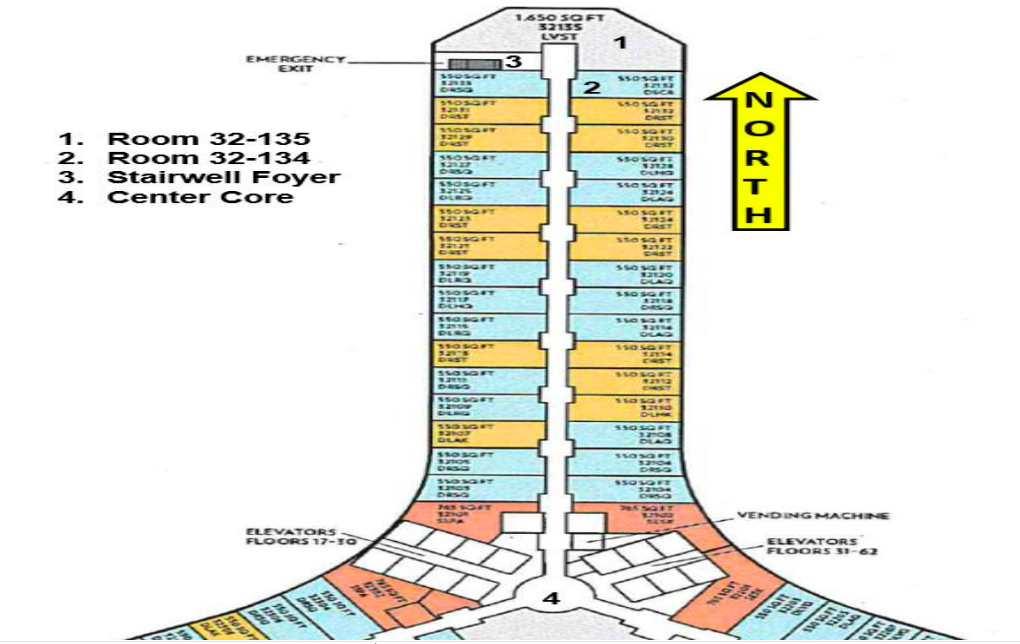

In the week before, Paddock had taken a room on the 32nd floor of the Mandalay Bay, and had transported multiple large bags [26] on different days, up into his room. A few days before, he had paid for the room next to the one he already had, one at the end of the hallway, both of which overlooked the Route 91 Country Music Festival.

He initially shot into the crowd with multiple weapons, changing magazines, ultimately shooting over 1,100 rounds. At one point, he changed his aim and started to try and shoot at a fuel oil tank that was located in the vicinity. The belief is that he wanted to see if it could make that explode and luckily that didn’t happen.

Why do hotels in Vegas and elsewhere in the US not have cameras in corridors? They do exist in hotels in several other countries.

That is correct. They might be there in elevators, but not in passageways, or in rooms, obviously, the latter for privacy reasons. The hospitality industry, traditionally, has been trying to cater to clients, in terms of privacy issues, but I think there’s an understanding now of a need for some change here, on both sides, because of public safety and security. We are working with some organizations on this, on systems that would allow for the covert identification of weapons when someone comes through a door or walks into a lobby. We’ll be working with these organizations on the installation of Facial Recognition, Weapons Recognition and Shot Detection Systems.

There are newer systems now that can even detect the exact location of an elevated shooter. Things like that have been some of the major problems of the past — and these are problems that are being rapidly solved by advances in integrated technological security. One of the major issues we have traditionally had, for instance, is that law enforcement did not have the ability to identify a shooter if an individual was shooting from above street level. They basically could not identify where exactly the shot was coming from. But now, with new technology that was originally developed for the military being commercially available, this is an issue that can be dealt with, both by law enforcement and the private sector.

Private organizations, including hotels, are now looking to proactively have these plans in place to manage incidents. And they are not just looking at plans like these for active shooter situations after a shooting begins. They’re also implementing plans that will train their employees to look for red flags: For instance, if someone has a “Do Not Disturb” sign on a door for beyond a certain length of time, to get their housekeeping staff to file a report and have security go access that door. Also, to train their staff, both the cleaning staff and other housekeeping staff, to know what to look for when they go into a room, so you get additional pairs of eyes who can add to a security profile.

The Incident Response

There are different kinds of mass casualty events: A shooting is very different from a bombing is very different from a plane being downed. What does the initial assessment in responding to mass casualty incidents look like?

The initial response is very well practiced under the National Incident Management System or NIMS, from the local level police all the way up to the inter-agency model at the federal level, irrespective of the kind of incident. It’s always been a presidentially-directed development, but is also now part of a Presidential Policy Directive on National Preparedness for any kind of modern day threat, implemented through the DHS. What they did initially was create the ICS, an Incident Command System, the structure by which the response at all levels, in all jurisdictions, is controlled.

The emergency operations centers, in many cases, are already established, and they will have identified locations for all agencies that will have to respond to a mass casualty event. Now depending on the kind of event, the list of responding agencies will be modified. In the assessment phase, whoever is assessing the situation will need to look at whether it involves multiple bombs, or hazardous material. Let’s say there was nuclear or radiological material detected. In that situation, you know you’re going to need additional components from the Department of Energy and others that are experts in a certain area.

What happens when the source of a mass casualty attack is unknown?

In that case, it’s an almost Pavlovian response, people will flow into their assigned locations in an emergency operations center while information flows in. It is a very well practiced and well-coordinated response. For instance, it may end at the local level if it is a single shooter incident. It is still a tragic incident to a police department or a local community, but it is not a multiple site, multiple shooter incident, which would lead to a much larger response.

At which stage does the FBI get involved when something like Vegas or the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shooting in Parkland happens, they were both single shooter incidents too.

Immediately, and for two basic reasons: First, the scale of the incident and second, at least initially, when you’re still getting information on victims and there’s a lot of confusion, you don’t know what you’re dealing with. The FBI is involved until there is a determination that it doesn’t have a federal nexus. And even then, quite honestly, there are support mechanisms in place where we may lend specialty units, such as a hazardous material response team, or a bomb technician. We have specialty assets that can be provided whenever needed. There is a very well established command and control system — there are areas designated for SWAT teams, hostage negotiators, evidence response teams, it’s all very well structured.

- Transitions in the operational and tactical strategies from active shooter to barricaded suspect with hostages to terrorism.

- The dark and difficult layout of the nightclub.

- The safety and wellbeing of hostages and law enforcement.

- Coordinating different local, state, and federal agencies that had overlapping roles and different communications systems and protocols.

- The threat of secondary attacks and explosions with little information.

We just recently met with a city commissioner and a high level deputy chief within the Orlando police. They’ve had multiple incidents in their jurisdiction, including school shootings and the Pulse nightclub attack. They’ve also had situations that they haven’t seen before. Nightclub shootings in the United States aren’t exactly uncommon. To have one turn into a mass terror attack is.

Once it was determined that it was a more than ordinary shooting incident, there are tactics, trainings and procedures that kick into place. Every level of law enforcement is trained, for instance, that when we respond to a school shooting, the first four people that respond — and those four could be an FBI agent, a patrol officer, a secret service agent, and a local sheriff — could form a diamond formation, as an example, and enter the school. Do note that tactics and strategies are continuously evolving when it comes to active situations and what tactic to use depends on the situation, the available resources and the urgency of the case. At the end of the day, it’s about saving lives.

Tactics, Training, Teamwork

Just to clarify, this doesn’t mean you wouldn’t enter a building until four people get there, it means you’d have to do a real-time assessment of the situation on the fly. What happens to the children inside while you’re determining this?

The old way would have been, “let’s wait until the SWAT team gets here.” Now, when we determine that we can’t wait, like when there’s an active shooter situation and children inside, we have to do what we can to neutralize that threat. Four is ideal because if you go in with two, you’re both looking front, or front and back, and if the shooter comes in from a side doorway, you could both be dead in seconds and add to the casualty list, helping no one. You go in the diamond and all four sides are covered. Obviously, a lone individual could go in by himself, or herself, and also make a difference, but we’re trained to look at the situation on a case-by-case basis and see what works best in each situation. In this case, in Pulse, they responded, there was continuous shooting, it had turned from a mass shooting into an incident where they didn’t know if the shooter was in there or not, whether negotiations were needed, and what exactly was going on.

I’ve been in a situation where we went to effect an arrest, got into a shootout, one of our guys was shot badly, and ultimately, our team had to back out and that turned into a hostage situation. The transition from tactical to a slow-moving hostage situation calls for a different set of skills. There are individuals who are specifically trained to deal with those situations, and tactics where the SWAT team will take up positions where they are prepared to assault if the individual inside starts shooting again. A lot of it comes down to training.

What about the layout, like in the Pulse case? Or in Vegas, when you couldn’t quite tell what was happening?

The second issue you raised, with the dark and difficult layout and not having awareness about where you’re going or what you’re looking at, that’s an issue that can be tackled through technology and partnerships. At all levels of law enforcement, public-private partnerships exist with industries and businesses within local jurisdictions. Whether this means knowing how to contact the utility personnel for a block, or where to get the blueprints needed for a building, or get hold of a business owner or another employee not working that night, someone with inside knowledge of a store or restaurant or club, law enforcement does realize they need to engage with communities, and can’t possibly know everything about everyone, even at the local level.

And it’s important to constantly train. When you go into a situation in a building where there’s an individual you need to arrest, you’re doing a less-dynamic law enforcement “Clear.” It’s a slow, methodical process. If it turns into an active shooter scenario, it’s a more dynamic entry. That’s something that gets drilled and drilled into a tactical responder’s head.

Yes, absolutely. When I was with the FBI, I was in charge of countermeasures and preventions of Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD) attacks. We had done countless exercises with Las Vegas. Everything from responding to a food borne attack at a salad bar at one of the hotel properties to shootings and explosions, to chemical attacks. They were very well practiced.

Collaboration & Communication Post 9/11

There was an exponential rise in global terrorism post 9/11, in terror attacks around the world, and in threats against the United States by various terrorist groups, especially with our involvement in the War on Terror on various fronts. However despite all that, there hasn’t been a 9/11-like attack on U.S. soil in the 17 years since then. What would you attribute that to?

I think one of the other major changes was that they fixed the system, so all of the intelligence agencies would talk to each other. There are 17 identified intelligence agencies in the U.S. and in the old days, I’d say pre-9/11, they didn’t talk to each other. They maintained their information and they didn’t share it. Information lived in silos. That got fixed, some of it was by mandate and some of it was by opening doors and putting liaison officers in each others’ space, so that they could get information in real time and pass on what needed to be passed on without delay. It really helped with us being able to coordinate all of our efforts and have better results.

Additionally, on the military side, our being able to stay on the offensive, both against terrorist havens, plus stopping them from being able to proactively plan major events by disrupting supply chains, meant that terror groups had to shift to attempt to reach out to their audience via the Internet, to try and find self-radicalized individuals and different means of attack. As a result, we have begun seeing these calls for individuals to make a difference and subsequent attacks by people armed with machetes and hammers and knives, or by those that drive vehicles into crowds of pedestrians. We’re seeing a bit of a shift in the type of attack, but at this point, we’re not seeing the large, grandiose terrorist attack.

Tackling The Lone Wolf

Moving away from terrorism to other attacks, irrespective of whether a religious or other ideological belief fuels them, or just anger — is there any way to control the lone wolf attack?

I would say no. There are lots of ways to identify them. We do a lot of work on social media, monitoring, and scrubbing. We use human intelligence networks, we use electronic means, but if we have an individual such as Paddock, who showed no signs, communicated with nobody, and did it all on his own, we’re really back to seeing if we can stop the method of attack. Can we stop him from bringing weapons into a building where he’s going to shoot down into a crowd? It has to be a multi-layered approach. We have to do as much on the proactive prevention side as possible, but when that doesn’t work, and there will be times it doesn’t, we’re prepared to mitigate with a very practiced, well trained response.

Are there benefits to crowdsourcing investigations in mass casualty incidents like the Boston Bombing? In this world of the omnipresent smartphone and social media, the general public often has access to photo and video footage and may have seen or heard important details about the incident? How do you collect this information and sift through it in real time? There were also people that got badly hurt at that time, with false identifications broadcast in the media, which portrayed them as terrorists.

I think there are great benefits to crowdsourcing, typically when it comes to identification of an individual, but we’ve got to be very careful. I think we’ve seen great success at every level of law enforcement with asking for help from a community but you have to be a bit careful with the utilization of the media, depending on the situation. If it were a hostage situation, for example, and you were providing live coverage of where the SWAT teams were and the individual inside was able to watch TV and see it happening live, that’s a completely different situation.

Crowdsourcing has tremendous benefits, but there is a process that has to be followed and it can’t be avoided. You know this, through the work you all do, that there are a great many advances in biometrics that give you the ability to identify an individual in real time, and utilize that imagery to scan his or her face. There are multiple sources of media that come in much faster than when we were working in the past, and these are good tools. But there are cases where, through the investigative process, you have to prioritize which film you want to look at from what angle, and that’s really about applying old-fashioned investigative training and thinking to modern day tools, along with common sense. Otherwise, there will be problems.

Future Threat: Disaster Delivery

Is there a different kind of mass casualty incident of the future that we need to keep a watch out for, with technology changing the world, and making it a more accessible one?

Yes, there is a current threat I’m more concerned about — and do keep in mind that with my background in weapons of mass destruction, I’m always concerned about a large chemical attack and disbursement in some way, or a biological attack. But right now, the drone attack is my major concern. There are reasons for that.

One, they are so easy to get hold of. Two, they’re being increasingly utilized overseas against our forces by ISIS and other groups, and being documented all over the Internet in propaganda publications. Three, there’s been testing with drones where you can automate a drone to hold an automatic weapon and target from the drone, from the controller. With their presence in conflict areas increasing, typically, that’s a sign that lone wolves or self-radicalized individuals could utilize drones in the near future in attacks on the home front. And I’m always concerned about the proliferation of information out there about chemicals that can be utilized to make explosives, picked up at any Home Depot or other hardware store, and now, delivered via an unmanned aerial vehicle.

What about 3D printed guns?

It is a concern in that they can defeat a metal detector, but they are less of a concern inasmuch that in all the testing so far, they’ve really been proven to be single-shot weapons. So they can’t be used, at least for the moment that we are aware, in mass shootings of the kind we have been seeing, as a multiple shot firearm, or a semiautomatic.

Bumping Up Background Checks

Let’s keep the politics of it all aside for a minute. From a law enforcement perspective, is there a need for some sort of gun control? What does the law enforcement community believe? We’re not talking about taking away the Second Amendment here. Is there a need to put in safeguards, and if so, what would those look like, whether they’re restrictions on modifying bump-fire stocks, semiautomatic rifles, the sale of ammunition, more stringent and longer background checks, what can be done and what is being done, what should be done?

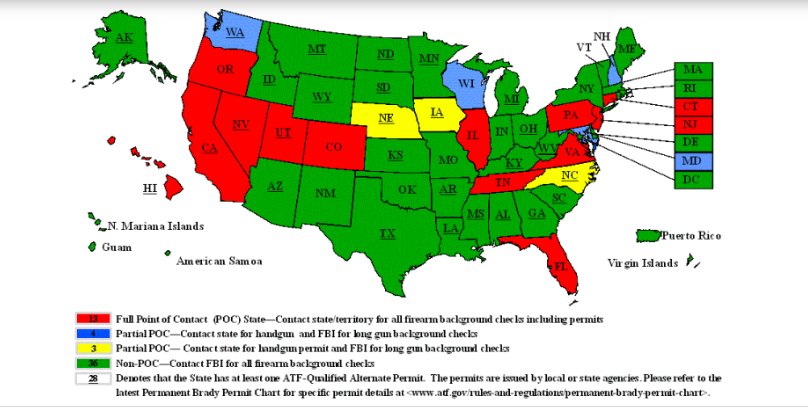

Everyone I talk to, whether from law enforcement or from industry and looking at it from the perspective of being a target, everyone recognizes that we’re not looking to intrude on a citizen’s Second Amendment rights, but there does seem to be a fairly common thread to what they feel about possible solutions. Most involve more stringent background checks, and integrating the background check system, or more specifically, the weapon purchasing system, with the public health and mental health database.

[Editor’s note: A semiautomatic rifle fires a single round every time you squeeze the trigger. Automatic rifles, banned for civilian sale unless they are manufactured pre-1986 when restrictions on sale came into place, fires nonstop as long as you can hold down the trigger. A bump-fire stock replaces the part of the rifle that rests against your shoulder, and includes a design that allows a shooter to keep a finger on the trigger, helped by the gun’s recoil, increasing the rate of fire.]

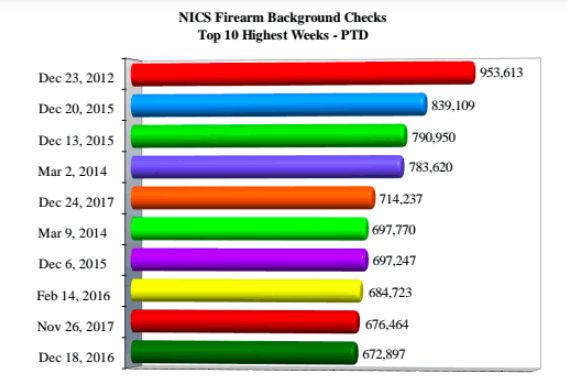

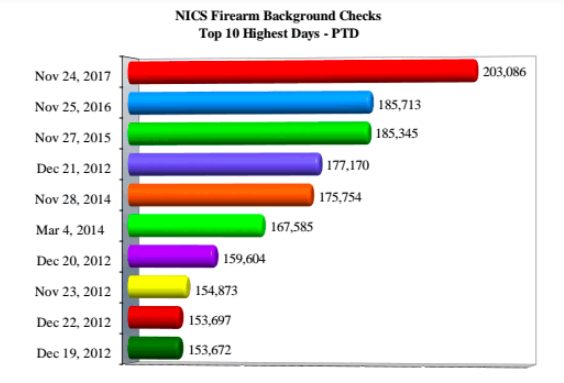

- NICS, the FBI’s National Instant Criminal Background Check System, had its highest ever week just days after the Dec. 14, 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary School massacre, when Adam Lanza murdered 20 children and 6 adults, after previously killing his mother at their Newtown home,

- The second and third highest weeks were after the Dec. 2, 2015 San Bernardino terrorist attack, in which Syed Rizwan Farook and Tashfeen Malik, killed 14 people and injured 22.

- Two of the highest weeks were in 2017, both around the holidays. During 2017, in fact, NICS experienced two of its all-time top weeks for volume of background checks processed.

- NICS observes an uptick in transaction activity associated with hunting seasons, expectedly, and also with the yearend holidays. The day after Thanksgiving is a traditionally high day for processing NICS background checks, with the 2017 day after Thanksgiving being the highest ever, to date.

- Thanksgiving last year was less than three weeks after the Sutherland Springs massacre in Texas, when Devin Patrick Kelley, an Air Force veteran who had been court-martialed in 2012 for beating his wife and child, walked into a tiny Baptist church in the rural Texas town, and turned a quiet Sunday service into bloody carnage, murdering 26 people in quick time.

A QUICK EXPLAINER: THE DIFFERENT BACKGROUND CHECKING SYSTEMS

Interstate Identification Index (III): The III maintains subject criminal history records. As of Dec. 31, 2017, the III records available to be searched by the NICS during a background check numbered 75,950,530.

National Crime Information Center (NCIC): The NCIC contains data on persons who are the subjects of protection orders or active criminal warrants, immigration violators, and others. As of Dec. 31, 2017, NCIC records available to be searched by the NICS during a background check numbered 6,430,380.

NICS Indices: The NICS Indices, a database created specifically for the NICS, contain information contributed by local, state federal and tribal agencies pertaining to persons prohibited from possessing or receiving a firearm pursuant to state and/or federal law. Typically, the records maintained in the NICS Indices are not available via the III or the NCIC. As of Dec. 31, 2017, the NICS Indices contained 17,399,461 records.

ICE: The relevant databases of the ICE are searched by NICS for non-US citizens attempting to receive firearms in the United States. In 2017, the NICS Section and the Point of Contact (POC) states (states that have implemented a state-based NICS program), sent 214,823 such queries to the ICE. From February 2002 to Dec. 31, 2017, the ICE conducted more than 1,186,167 queries in support of the NICS.

Courtesy: The 2017 FBI NICS Operations Report

You really think anyone’s going to agree to combining the databases, with the rules around the HIPAA Privacy laws? Plus, on the practical side, determining which mental health issue disallows you from owning a weapon could make it very difficult to get a weapon; and who would determine that? It might be a slippery slope.

That’s probably the biggest and the most difficult issue to tackle, with the most obstacles, because of privacy issues related to medical records. However, if people look at it from a common sense perspective, this is an issue that absolutely needs to be solved. We can put as many privacy measures in place as needed, and restrictions in terms of access to the database as necessary, but those seem to be the common thread, when we talk to law enforcement or industry, on what we need to do — we do have to look at mental health.

Why not control the kind of weapon that’s available to civilians — that seems far simpler?

I think that’s because there’s a belief within the law enforcement community that whether it’s a 15-round magazine versus a 40-round magazine, in the end, it doesn’t really matter if you’re dealing with a trained individual. I can shoot as many rounds in one minute from a handgun if I have five 12-round magazines, as if I had two 30-round magazines on a semiautomatic rifle. Having been a SWAT Team operator and a sniper, and very familiar with weapons, if you have someone that wants to conduct an attack with a weapon, that’s splitting hairs. It’s really important to integrate the mental health and public health and weapon purchase systems, so there can be an alert and restrictions put in place ahead of an incident.

I’d like to bring up something you just said. You’re a former Navy officer, you’ve served in a war zone during Desert Storm. You’ve been an FBI agent, on SWAT Teams, and are a trained sniper. Most mass shooters, especially school shooters, don’t have your profile or your discipline. They may have some training, but a lot of them are antisocial, tend to be loners, and have exhibited, in many cases, some pattern of escalation — whether it was Omar Mateen, who abused his wife, James T. Hodgkinson, the Congressional shooter, Jarrod W. Ramos, the Capital Gazette shooter, both of who had documented anger issues. Does everyone have to have access to all weapons?

I think in the end, there are layers of prevention that can be put in place both to identify an individual that can be planning an attack, and to stop them from entering a building or property with a weapon. In the Annapolis Capital Gazette attack in June 2018, which happened seven miles from where I live, through a series of events — the local cops had just had a training exercise on mass shootings, they had just had a shift change, they had instituted a policy by which officers could take patrol cars home so they could get to places quickly in case of emergencies, and they had a sub-station half a mile away — they had double the number of law enforcement on the street and in double quick time.

Because they got there as quickly as they did, they were able to save as many people as they could. There were 11 people there; 5 were killed, 6 were not able to get out because the perpetrator had barricaded the back entry with a blocking device. But he did not have a high-caliber, multi-round semiautomatic rifle; he had a shotgun. You have to try and prevent an attack when you can. That can be done by providing better information to people that are there in an office, or a school, or a nightclub, or concert, or to the responding police. Obviously, one death is too many, and you want to be able to stop it, but you also want to be able to save as many as you can and be able to interdict it if you can’t stop it for some reason.

There is broad agreement, even among the more rigid Second Amendment supporters, that we should have more stringent background checks when it comes to weapons purchases, and that we should find a way to integrate that with mental and public health databases. We should do what we can do.

Security: Coexisting With Convenience

If you grow up in several other places in the world, you have metal detectors in malls and hotels, just like in airports here. It becomes an accepted part of life. Is that something that is potentially an American reality in the future because of lone wolf attacks that are hard to predict, despite the work of American intelligence in being able to prevent mass casualty terror attacks, so far, since 9/11?

It will be, we’re seeing a very significant uptick in industries and law enforcement that are asking for new technologies. This is a field I now work in, and there are new-to-market technologies out there, particularly in metal detection or shot detection or biometrics, that are covert. One of the biggest issues with industry, especially with places like Las Vegas that live off the tourism industry, is that they don’t want the security to be omnipresent, and they don’t want to inconvenience people — that’s a big thing. Some of the new technologies allow a free flow of people; you don’t have to empty pockets or bags unless they are metal bags. It really allows you to have security in place and enhance your security significantly, and it would have made a difference in the Paddock case, because every single bag that he dragged through the doorway would have registered and security would have been alerted.

What you’re saying is that despite events, including mass casualty incidents, people in industry are still looking for solutions that have to seamlessly integrate new security technology into buildings that are not a) overt and b) do not inconvenience customers or clients who enter the premises.

Yes, exactly. They are looking for that, and frankly, the technology is available now.

A demonstration of the ShotPoint Security Technology on March 6, 2018, at the Silver Eagle Group Range in Ashburn, Virginia, which was witnessed by Jeff Muller and his associates at MGI. ShotPoint is a sensor network system, where sensors mounted on walls, ceilings or integrated into outdoor lighting continuously listen for shots. This video is the property of the Databuoy Corporation and is published with permission, courtesy of Jeff Muller.

What about integrating the technology directly into a building and building technology itself, especially with smart cities?

We’re working at the federal and state level, and with the larger engineering and appliance companies on projects that do incorporate this; things like new LED lighting systems that Smart Cities project are going to be installing. We have integrated our ShotDetection system in that with a complete focus on preventing mass casualties, and giving people as much information as possible, in real-time, whether it’s first responders or it’s concert-goers. For instance, if they had a software app on their phone, and shooting started, they would know immediately, where those shots were coming from. So for self-evacuation for example, they would know what their best choice was.

Think of a teacher in a school. They’d get an immediate alert on their phone that there were shots fired, and that they had an active shooter situation. In addition, let’s say that it was a large high school; they may get the information that the shot came from the northeast side of the school. Well if you’re on the south or the southwest side of the school, it may not be the best option to lock your flimsy wooden door and hunker down with your kids, and hope that someone gets the shooter before the shooter gets to your classroom. Your best option might be to evacuate your class in the safe direction, instead of waiting.

Technology For The Good

Is it practical to expect school systems that don’t have enough money to pay for books, or pay teachers, or have buildings that are dilapidated, and very little to spend on special education programs, schools in more economically depressed neighborhoods, many with higher crime, some in minority majority areas, to find the money to pay for these technologies? All of this technology is undoubtedly lifesaving, but will also undoubtedly come with a substantial price tag. Would we be then creating two separate classes of school systems, one where the privileged can afford these lifesaving technologies and others cannot? How do we solve that?

Actually, what we’re doing is working with both federal and state legislatures on this because of some of these very issues. I’ll use New York because I think it’s a perfect example of what’s possible if there’s a will and a belief that this is necessary, without taking this money away from something else that is essential. We briefed their Senate Majority Leader and what they called their state Security Council in New York, and most of their senior state senators.

They are putting together a School Security Bill for $2 billion – they’re going to be voting on it at the end of the year. This is for every public school in New York — 5,600 schools across the state. There’s no differentiation between the schools. They are looking for a standardized solution using technologies that they would utilize. There is federal funding available and they are also looking at state bond funding. So it would essentially be a 10-year program. Different states are looking at different ways to utilize both federal dollars and generate additional dollars at the state level for school security, dollars that are outside what they already give to schools, so you’re not taking away from book supplies, or teachers or special ed.

A Note About This Series

Running from mid-September to Oct. 1, the one-year anniversary of the Las Vegas shooting, this was a four-part series in lieu of the Missing & Unidentified Persons Conference (MUPC), which is skipping a year as it moves to Las Vegas for its 12th edition in 2019. Each piece featured an expert and focused on an aspect of law enforcement and other public safety response to missing persons and mass casualty incidents: Urban Search and Rescue; Forensic Imaging in Missing Children Cases; Investigations focused on At-Risk Communities, Including Human Trafficking; And Mass Violence and Terrorism. This was the fourth and final piece of this series, which was a collaboration between the NCJTC and Biometrica Systems, Inc. You can register for the 2019 MUPC event here.

In addition to the NCJTC, we are especially grateful to the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children (NCMEC), the National Association for Search and Rescue (NASAR), the Bay Area Search and Rescue Council (BASARC), Muller Group International (MGI), Ryan United, Chris Young, Jeff Muller, Collin McNally, Derek VanLuchene, Nadia Eley and Priyanka Oberoi for all their patience and generosity in working with Biometrica on this community education initiative.

You can email the writer with suggestions for other series or anything else at kmurali@biometrica.com