Lone Wolf Terrorism: The Greatest Domestic Terror Threat Today

By Deepti Govind

When one talks of a terror attack, people are most likely to conjure up images of a group of masked assailants, with some kind of weaponry, hijacking a plane. That’s the lasting effect that images and videos of the 9/11 attacks created, more so, of course, on those who were present on that fateful day and those old enough to remember it across the world. In any case, there’s no doubt of the transcendent impact of the terror attacks of Sept. 11 2001. A total of nineteen militants associated with the extremist group Al Qaeda, were involved in carrying out the events that led to the hijacking of four aircrafts.

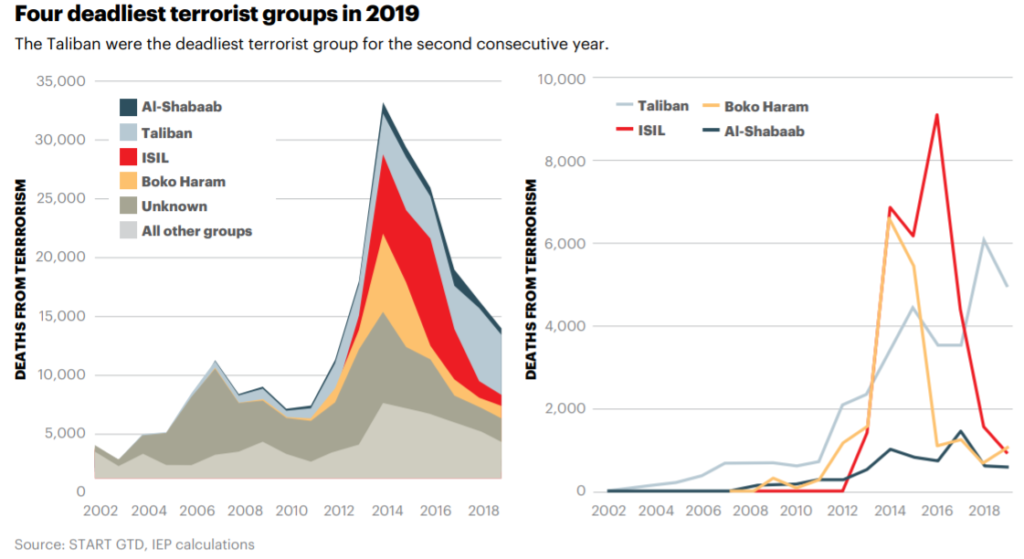

But a majority of terror attacks since have not happened in a similar manner, and have rarely involved so many actors working together. In fact, since 2006, 98% of all deaths from terrorism in the U.S. have been the result of attacks carried out by lone actors, according to a 2017 report on terrorism. In the United States, both Islamist and far-right terrorism are displaying a shift away from affiliations with specific groups towards lone actors who are driven by a specific ideology, but who are not formally tied to a specific terrorist group. Of 53 recorded attacks in the U.S. in 2019, only two were attributed to a specific terrorist group, says the Institute for Economics & Peace’s (IEP) 2020 Global Terrorism Index report.

What has, perhaps, also played a role is the location in which terror attacks have happened in recent times. Staging an attack onboard an aircraft remains a prime target for terror groups, but aviation security has come miles over the last two decades, making it a much harder target. Logically, hijacking a plane would also be incredibly tough for a lone wolf actor to pull off.

For instance, the 19 terrorists who executed the Al Qaeda’s 9/11 attacks were divided into “teams” in order to bring down the four planes: Two planes were flown into the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center in New York City, a third hit the Pentagon just outside Washington, D.C., and the fourth crashed in a field in Shanksville, Pennsylvania. In and among the 2,996 people who died at the WTC were hundreds of first responders: 343 firefighters and paramedics, 23 New York City police officers, and 37 Port Authority police officers.

But terror attacks have been known to happen in other modes of transport too — on trains, for instance. All manner of “public spaces” have also been used by terrorists to stage attacks: from streets to office buildings, marathons to bicycle tracks, synagogues to churches, and stadiums to government buildings. Unlike aircrafts, airports, or other transportation locations that now have better security practices, the lone wolf terrorist can access some of these public spaces with much more ease and convenience than others.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) warned in a joint report in May this year that “the greatest terrorism threat to the Homeland we face today is posed by lone offenders, often radicalized online, who look to attack soft targets with easily accessible weapons. Many of these violent extremists are motivated and inspired by a mix of socio-political goals and personal grievances against their targets.” But the rise in lone offender terrorism — or “lone wolf” terrorism, as its also known — is not new.

In this piece, we look at the evolution of the lone wolf threat in the United States in brief, take you through a few examples where lone offenders have managed to pull off a major attack, and examine whether they can be considered to be truly acting “entirely alone,” given their influences.

The Evolution Of The Lone Wolf Offender

Concerns over an increasing number of lone wolf offenders predates 9/11. It was in the early 1990s that law enforcement authorities became increasingly concerned about the advent of such terrorism, according to a research brief published by the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START) in 2014. “The extreme right began advocating this ‘uncoordinated violence’ approach in 1992 under what was called a ‘leaderless resistance’ model. It was around this time that the emergence of the Internet allowed cyberspace to become a major source of radical propagandizing for environmental terrorists and al-Qaida-inspired movements,” the brief adds.

Although lone actor terror incidents were rare at that point, the START research brief said they were nevertheless responsible for a disproportionate 25% of all terrorism incidents in the U.S. back then.

In the U.S., it’s not only jihadist terrorism that’s been on the rise and that has been increasingly seeing lone wolf actors getting involved. As we mentioned earlier, there’s also far-right terrorism, and several other kinds besides. These actors could all fall under the government definition of Domestic Violent Extremists (DVE). When it comes to domestic terrorism, lone offenders will continue to be the primary actors, and will continue “to pose significant mitigation challenges due to their capacity for independent radicalization and mobilization and preference for easily accessible weapons,” the FBI and the DHS said in their joint report from May.

The FBI and the DHS define a lone offender as “an individual motivated by one or more violent extremist ideologies who, operating alone, supports or engages in acts of unlawful violence in furtherance of that ideology or ideologies that may involve influence from a larger terrorist organization or a foreign actor.” Over the years there’s been disagreement over what kind of violent acts ought to be classified as terrorism. It can be argued that infliction of fear upon a targeted group or the public is sufficient to classify an act as terrorism. But the Bureau’s definition of terrorism also requires a “a purported motivation that goes beyond exclusively personal motivations and attempts to influence change in furtherance of extremist ideologies of a social, political, religious, racial or environmental nature.”

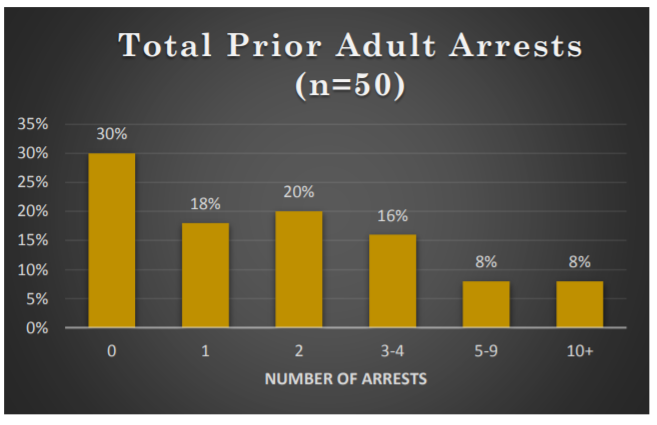

In 2019, the FBI published a study that analyzed 52 lone offender attacks in the U.S. since 1972. Among other aspects, that report tried to identify demographic trends and similarities among lone offenders. It discovered that the offenders varied widely in characteristics like age, race, relationship status, and educational background. Consistent with other studies, it arrived at the conclusion that there’s no real profile of a lone offender that can be drawn, though there were some factors overwhelmingly represented.

For instance, all 52 offenders in the FBI study were male, although women can and have engaged in acts of targeted violence through history too, of course. The youngest offender was 15 years old and the oldest was 88, with the average age at the time of the attack being 37.7 years old. Among radical Islamic extremists, the study says, the average age was a much younger — 26.3 years. Most offenders (90%), contrary to popular belief, were not foreigners or immigrants but were born in the United States; and in terms of race, a majority of them were white.

Nearly half of all offenders were also not in a relationship at the time of the attack, and over half were neither employed nor attending school. Still, most had completed an associate’s degree or at least some college education. Of 26 offenders who identified as religious, 50% identified as Christian and 35% as Muslim. Almost 70% of the offenders were arrested at least once as an adult before carrying out their attack.

A quarter were diagnosed with one or more psychiatric disorders at some point before their attack. There were other psychiatric factors that played a role, per the study — paranoia, for example. More than half of the offenders demonstrated a pervasive distrust and suspiciousness of others, or a belief that others were plotting to harm them. Then there were other issues including delusion, grandiosity, and even cases of hallucinations among a few of the offenders. Nearly 40% of them had also expressed suicidal ideation at some point before they carried out their attack. Half the offenders had also exhibited some evidence of prior drug use.

Radicalization as a process is difficult to discern fully and can be non-linear and shaped, in many ways, by an individual’s private thoughts, experiences and opinions. Per the FBI study, it is “the process through which an individual transitions from a nonviolent belief system to a belief system to actively advocate, facilitate, or use unlawful violence is necessary and justified to affect societal or political change.” What somewhat separates lone offenders from those that belong to a terror group, or who are directed to carry out an act by a terror group, is that lone wolves claim their violence is done in service of larger ideological goals, like inciting social or political change.

It’s not just the U.S. that’s grappling with lone wolf acts, though. Just last month, Europol published its third annual report on Online Jihadist Propaganda. In that report, it said propaganda from both the Islamic State and Al Qaeda continue to call for lone actor attacks by individuals who have no physical connections to either group. Why does that matter? In another report published June, for instance, Europol noted that the number of completed jihadist attacks in Europe (EU, Switzerland, and the UK) in 2020 more than doubled in comparison with the number in the EU (including the UK) in 2019. The one common factor between all the completed jihadist terror attacks was that they were carried out by lone actors, while disrupted plots mainly involved multiple suspects.

The difference between lone wolf acts in Europe and the United States, per FBI-DHS statements and Europol, is that in the EU it’s still jihadist terrorism that’s responsible for many lone offender attacks. And that is not entirely a lone wolf act either, since the Islamic State and Al Qaeda are also either directing or inspiring these individual actors.

Major Lone Offender Attacks

In 2020, the FBI’s director, Christopher Wray, stressed the importance of lone wolf offenders. “The FBI is most concerned about lone offender attacks, primarily shootings, as they have served as the dominant lethal mode for domestic violent extremist attacks. More deaths were caused by DVEs than international terrorists in recent years. In fact, 2019 was the deadliest year for domestic extremist violence since the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995,” he said.

The same technological advances used by many of us to make our everyday lives more convenient can also be misused by criminals and terror actors. It’s a well known fact that cybercrime is often much more complicated for law enforcement officers and investigators to crack than crimes committed in the physical world. And the cyber world is increasingly becoming a target for all manner of criminals.

For instance, in December 2019, then 21-year-old Mohammed Saeed Alshamrani was able to communicate using warrant-proof, end-to-end encrypted apps to deliberately evade detection by law enforcement to plan his attack at Naval Air Station Pensacola in Florida. “The online, encrypted nature of radicalization, along with the insular nature of most of today’s attack plotters, leaves investigators with fewer dots to connect,” the FBI Director said of that particular case. Alshamrani’s shooting at the naval air station, where he was training, killed three U.S. sailors and severely wounded eight other Americans.

“It took the FBI several months to access information in his phones, during which time we did not know whether he was a lone wolf actor or whether his associates may have been plotting additional terrorist attacks,” the FBI Director said. In May 2020, the FBI said he had “significant ties” to Al Qaeda, citing new evidence gleaned from iPhones the FBI was able to unlock after months of trying. They also discovered, upon unlocking the phones, that Alshamrani’s preparations for terrorism began years ago. He had, in fact, been radicalized as early as 2015.

It’s not just jihadist terrorism, as we mentioned earlier, nor is it individuals who have a clear affiliation or are inspired by a designated terror or extremist group that have carried out lone wolf attacks.

In March this year, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (DNI) — the nation’s premier intelligence office — in a declassified report warned that DVE poses an “elevated threat” in 2021, particularly white supremacist organizations. The report singled out “racially or ethnically motivated violent extremists” and anti-government/authority militias, the former being most likely to “conduct mass-casualty attacks against civilians,” and the latter most likely to “target law enforcement and government personnel and facilities.”

An example of that is Dylann Roof’s 2015 murder of nine Black churchgoers in Charleston. In August, a federal appeals court upheld Roof’s conviction and death sentence for the racist slayings and said the legal record cannot even capture the “full horror” of what he did. One report says Roof became more radicalized as he grew enthralled with white supremacist communities online.

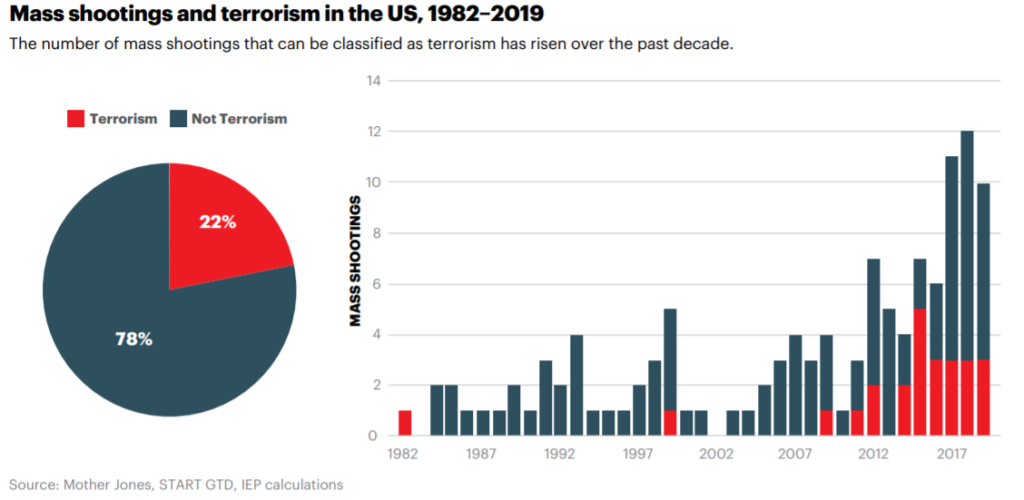

Since 9/11, there has been a blurring of boundaries between hate crimes, mass shootings, lone offender attacks, and terrorism — most of which is a legal conundrum, more than a theoretical or practical one. What we are witnessing in the national security landscape today, according to some experts, is the transformation of routine, generic grievances into larger acts of terror and violence.

For instance, the 2016 shooting at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Florida. Although it’s not on the FBI-designated list of domestic terrorism incidents from 2015 through 2019, it can be considered an example of that blurring of lines between mass shootings, lone offender attacks, and terrorism. That fateful weekend night was Latin Night at Pulse, one of the city’s best-known gay clubs, and the place was packed with patrons both gay and straight, young and not-so-young, from the U.S., Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, Mexico, and elsewhere, having a good time dancing salsa and bachata, says an NPR report.

At 2:02 a.m., according to an FBI timeline, Orlando police received reports that multiple shots had been fired at Pulse. In all, the lone gunman, Omar Mateen, killed 49 people and injured dozens of others. He pledged allegiance to the Islamic State in a 911 call after the shooting began.

Then there are other radical motivations for acts of domestic terrorism, like the Planned Parenthood shooting, which is on the FBI-designated domestic terrorism list. In 2015, Robert Dear Jr. attacked a Planned Parenthood facility in Colorado Springs, shooting and killing three people and injuring multiple others. He said he attacked the clinic because he was “upset with them performing abortions and [with] the selling of baby parts.” He admitted to fatally shooting an arriving police officer through a tinted window because he knew the officer couldn’t see him. He also told police he dreamed he would be “met in Heaven by aborted fetuses wanting to thank him for saving unborn babies,” a USA Today report said.

Then there are hate crime incidents, which also do not fall under the official designation of terrorism but lie where in the gray. For example, various nationwide synagogue attacks, and the rise since last year in anti-Asian hate crimes.

Are They Truly Isolated?

As part of its 2019 study, the FBI says lone offenders are seldom completely isolated. True, these attacks are tougher to predict. But, the Bureau encourages the public to follow the government’s “see something, say something” advice to help prevent such terror acts. Most offenders had “family, peers, or online contacts who were in a position to notice troubling behavior.”

Drawing the links between lone wolf attacks them actually paints a more sinister and insidious picture, Aara Ramesh wrote in our second feature in this post-9/11 series. In some ways, individuals with similar grievances are organizing online, shirking labels of just being unhappy “trolls” in their own “internet echo chamber.” For instance, there has been a rise in the number of mass murder incidents tied to misogyny, perpetrated by self-described “incels” (involuntary celibates). They may, at the moment, lack a central leader or mastermind a la Osama bin Laden or Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, but they are still displaying signs of nascent organization and cohesion.

It is seemingly evident that though they are not motivated by religion, many of these criminals are motivated by some shared ideology. They gather in a place together — online — and feed into each other’s rhetoric, encouraging violence and revenge. In fact, mass murderers like Roof and Rodgers often leave behind written or recorded “manifestos,” that are passed around by similarly minded people online and are even referred to by subsequent murderers.

In 2018, a Pacific Standard report said even the lone wolf white American terrorists are radicalized in “packs.” They’re reading the same websites, talking to each other, and killing the same targets, the report adds. Elliot Rodger’s 2014 shooting spree in Santa Barbara was also a result of radicalization. The Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) called Rodger the country’s first “alt-right” killer. In early 2018, the SPLC said it had counted over 100 people killed or injured by alleged perpetrators influenced by the so-called “alt-right” — a movement that, it added, continues to access the mainstream and reach young recruits.

Terrorists and those who run amok are similar, whatever their ideology, criminologist Britta Bannenberg said in an interview with Deutsche Welle (DW), Germany’s international broadcaster. “Most often, individual perpetrators are people with few or no social contacts. So what do they do? They go online and seek out those forums that reinforce their hate and rejection of others or other groups,” she says in the interview.

Whatever the case, there’s no doubt that lone offender attacks are tougher to combat and connecting the dots in an investigation is that much more complicated. With the world increasingly being driven online, especially after the Covid-19 pandemic, and everyone from terror groups to individual actors adapting to the shift, it’s going to become a vital part of the fight against terrorism.

This was the final part of our series on the post-9/11 landscape.