Missing And Murdered Indigenous Persons: Is Change Finally On Its Way?

By Kadambari Wade

On Feb. 1, 2021, the Department of Justice (DOJ) published the first of two issues of their Department of Justice Journal of Federal Law and Practice focused on missing or murdered American Indians and Alaska Natives. This was part of a collaboration between the DOJ’s Missing and Murdered Indigenous Persons (MMIP) Initiative and the Presidential Task Force on Missing and Murdered American Indians and Alaska Natives (Operation Lady Justice).

Operation Lady Justice was a two-year task force established on Nov. 26, 2019, by Executive Order (EO) 13898, with a concentration on two areas: Missing persons cases and cases of murder. Why is this interesting? Because while the two issues are often clubbed together, from a policing perspective, and in terms of data, causes, and law enforcement responses, they’re very different. Missing person cases are not automatically tagged as a criminal investigation and being missing is not always a crime, murder invariably is. What was also interesting was that the Task Force adopted the terminology Missing and Murdered Native Americans or “MMNA” to include American Indian and Alaska Natives of all genders and age groups.

Why Was This Task Force Needed?

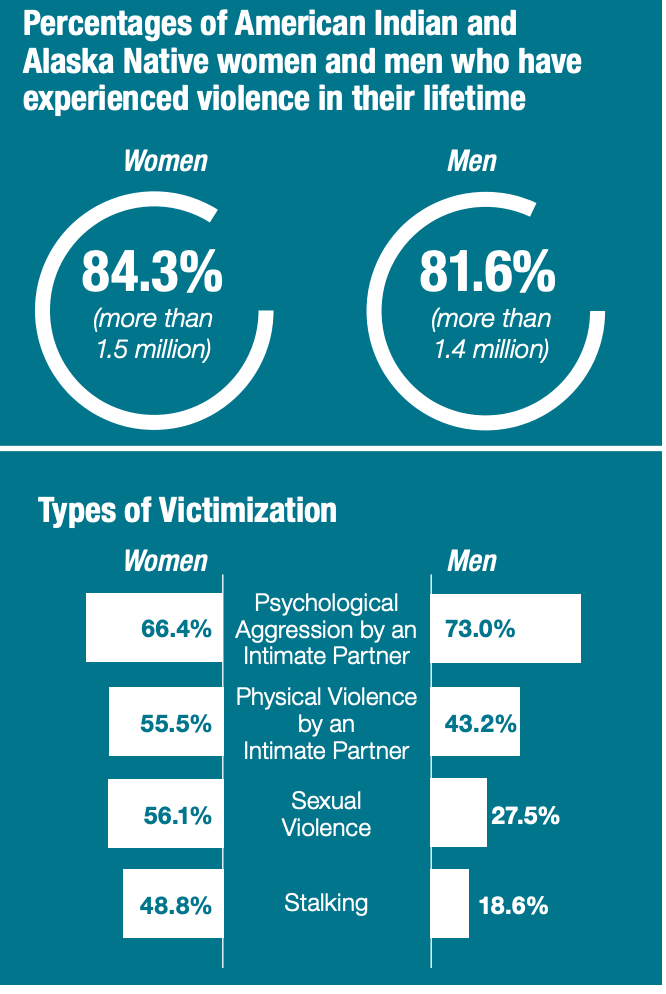

According to the almost 100-year-old Association of Indian Affairs, the country’s oldest nonprofit focused on Indian Country and protecting tribal interests and culture, an astounding 84.3% — four in five — of American Indian and Alaska Native women “have experienced violence in their lifetime” across North America, whether on reservations or in urban areas off tribal land. The stats, and it is generally believed these are widely underreported, are stark, American Indians and Alaska Natives are 2.5 times as likely to experience violent crimes and twice as likely to experience rape or sexual assault crimes compared to all other races.

According to statistics from the DOJ’s National Institute of Justice (NIJ), more than two in five American Indian and Alaska Native female victims reported being physically injured, and almost half reported needing services, including medical care and legal services, which more than a third (38%) were unable to access. In the U.S. and Canada, an average of 40% of the women who were victims of sex trafficking identified as American Indian or Alaskan Native.

And it isn’t just sexual assault or intimate partner violence. Read these two stats: Homicide is reportedly No. 3 on the list of causes of death of American Indian and Alaska Native women between 10 and 24, and the fifth leading cause of death for indigenous women between 25 and 34 years. As of 2017, which is apparently the latest available data, the top three cities with the highest number of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women & Girls (MMIWG) cases were Seattle; Albuquerque, and Anchorage while the top three states for such cases were New Mexico, Washington, and Arizona. All three states are among the 11 states that are a focus of the DOJ’s new Task Force program.

A June 2019 report from the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children (NCMEC) said that between Jan. 1, 2009 and Dec. 31, 2018, it had assisted with 1,909 cases involving missing Native American children. Of those, a majority (85%) were Endangered Runaway cases, with 12% being Family Abduction cases. A 10-year-analysis by NCMEC of this data indicated that almost 60% of the cases were female, while the mean age of the children that went missing was 14, with one-fourth being between 10-14 years. The report also said that more than a third (35%) of these children had at least one tribal affiliation. The five most common were Cherokee (46 children), Navajo (40 children), Sioux (35 children), Chippewa (33 children) and Alaska Native (31 children).

Behind Blurred Lines: Finding The Causes Of This Epidemic Of Crime

While the causes go back centuries, to sustained and historic systemic discrimination, appalling poverty, federal policy and the inequitable application of laws on tribal lands, this 21st century version of an ongoing crisis has an intriguing, if horrifying twist. A five-part Al Jazeera America project in 2015 on Native American gangs, stated, “Compared with their African-American or white counterparts, Native American gangs and gang members are a relatively new phenomenon, tracing their roots back to the 1980s and ’90s, when city gangs introduced themselves to Indian Country and began recruiting.” The article continued: “The growing threat of Native gangs is not a retelling of cowboys and Indians set against the backdrop of a modern black market. It’s a story about how historical trauma, federal policy and tribal pride have created a new Indian problem: Organized crime.”

The project referred to two telling statistics: Data from 2007, which showed that less than half of Native Americans aged 25 and over had a college or graduate degree. And a damning 2014 Aspen Institute report that asserted that Native American teens experience the highest suicide rate of any population group in the United States.

These facts, coupled with rising drug use across the country, within and beyond tribal lands, have also led to a renewed resolve to tackle a not-so-new problem that is quickly reaching epidemic proportions in Indian country: Human Trafficking. An article in Indian Country Today on Aug. 1, 2016, reported that a Northeastern State University study on methamphetamine use in tribal communities found several disturbing trends. “Organized criminal gangs are targeting casinos in tribal jurisdictions to facilitate drug sales and sex trafficking, and drugs are being trafficked by large non-Native organizations with international ties…”

Just for a perspective on the urgency of this last issue, here are some statistics. According to “The Devastating Impact of Human Trafficking of Native Women on Indian Reservations,” a transcript of the 2013 testimony of Lisa Brunner, of the National Indigenous Women’s Resource Center, to the U.S. Senate, “Native women experience violent victimization at a higher rate than any other [segment of the] U.S. population.”

It also stated: “Congressional findings are that Native American and Alaska Native women are raped [at the rate of] 34.1% — more than one in three will be raped in their lifetime; 64%, more than six in 10, will be physically assaulted. Native women are stalked [at] more than twice the rate of other women. Native women are murdered at more than 10 times the national average. Non-Indians commit 88% of violent crimes against Native women.”

Brunner’s testimony was deeply disturbing. It spoke of the sex trafficking and selling of Native American women for “$20 of heroin,” the predatory economics of “undocumented man-camps” after the fracking boom in North Dakota and Montana, which led, in turn, to a documented increase in multi-faceted criminal incidents; to the underground, unregulated adoption industry that thrives on selling Native American children “to the highest bidder.” In short, it said that unfortunately, human trafficking in Indian country was alive and kicking.

According to the NCMEC report mentioned above, 11% of missing Native American children intaked by them had a reported history of sexual abuse. The types of sexual abuse ranged from child sex trafficking (62% of all cases involving a history of sexual abuse), sexual abuse by a family member (10%), statutory rape (13%), and sexual assault by an acquaintance (4%).

There’s Work Being Done But It’s A Long And Complex Road

One of the major problems prior to 2013, and the signing of the Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2013, or “VAWA 2013,” Native Americans could not bring their offenders to justice on tribal land if they were not Indian. VAWA 2013 partially resolved this, at least for victims of domestic violence, when that violence occurs in Indian country, and when the victim is Native American.

Just to provide some context to why this was important: According to a 2018 report from the “Hate in America“ project, a Carnegie-Knight News21 initiative, unlike women of every other racial group, Native American women were far more likely to be sexually assaulted by people not of Native American origin. The report, quoting a study by the University of Delaware and the University of North Carolina, said that more than two-thirds of sexual assaults against indigenous women were committed by white and other non-Native American people, “yet non-native men who assault Native American women on reservations can’t be arrested or prosecuted by tribal authorities under a 1978 Supreme Court decision.”

The NIJ states that “most American Indian and Alaska Native victims have experienced at least one act of violence committed by an interracial perpetrator” — 97% of women and 90% of men — as compared to 35% of American Indian and Alaska native women and 33% of men experiencing one or more acts of violence by an American Indian or Alaska Native perpetrator.

In Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe, the United States Supreme Court, in a rather controversial 6-2 decision, decided that tribal courts have no criminal jurisdiction over non-Indians. VAWA 2013 recognized tribes’ inherent right to exercise “special domestic violence criminal jurisdiction” (SDVCJ) over certain defendants, who, regardless of their Indian or non-Indian status, committed acts of domestic violence or dating violence or violated protection orders in Indian country.

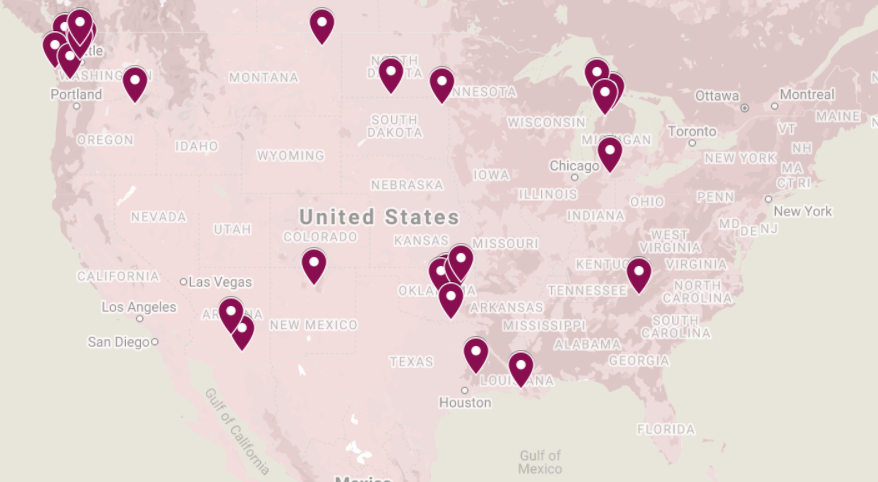

The problem, though, is that even almost eight years after the passage of VAWA 13, only 27 of 562 federally recognized tribes have become voluntary compliant with implementing VAWA SDVCJ across the United States. And its federal regulations and it requires voluntary compliance. (See map below).

According to a 2017 article by the Indian Law Resource Center (ILRC), one of the reasons for the slow adoption was regulations, “such as providing court appointed council to defendants who cannot afford it at the tribe’s expense, a challenge for tribes with little money.” Another issue? “Tribes must also have juries that are selected from a “fair cross-section” of the public,” which meant they could not exclude non-Indians. According to the ILRC, “while this was practiced by some tribes even prior to the VAWA reauthorization, for others it means changing tribal law.” They gave the example of the Cherokee Nation, which had otherwise met the regulations.

The article quoted Chrissi Nimmo, the assistant Attorney General for the Cherokee Nation since 2008, who said then, “We still have to pass legislation to include non-Indians on our jury. How do we, as an Indian tribe, want to open up our court system to non-Indians? It’s always been Cherokees. How do we carve out this special seating? I don’t have a timeline but to say that we are working on it.” AG Nimmo and the Cherokee Nation did work on it. As of February 2021, they are one of the 27 Tribes implementing VAWA 2013.

You can find the full list of Tribes here.

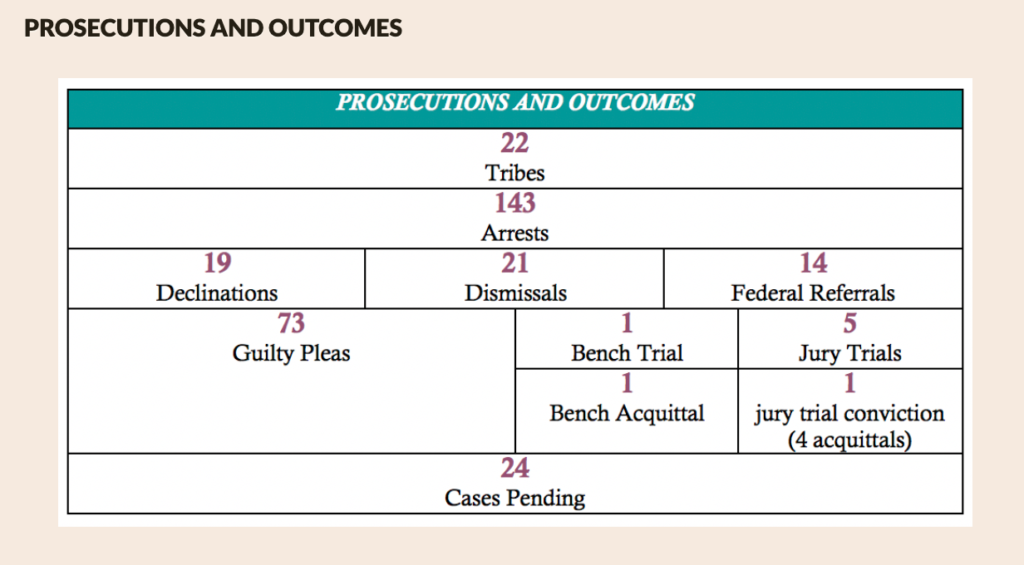

Change is Going To Come? One-Year On, A Report from Operation Lady Justice

Where is this all going? In November 2020, a 78-page, one-year OLJ report put together and detailed several suggestions, including those from listening sessions with tribal leaders. These included:

- The need for a deep dive into the root causes of missing and murdered American Indian and Alaska Native peoples.

- An improvement in interagency collaboration across all agencies.

- Full funding for Tribal law enforcement, courts, social services, domestic violence shelters, victim services programs, domestic violence and sexual assault community organizations, and search teams.

- A need for publicly available data on missing persons and murder cases.

- Increased State and local training on Tribal issues including enforcement of Tribal court orders of protection.

- A need to establish a national alert system for adults similar to Amber Alert.

- Better Federal communication with families and grassroots organizations.

- Tribal notification when a person goes missing.

- Programs to address intervention and prevention.

- Increased access to the Tribal Access Program, as well as increased availability for Amber, Ashanti, and Silver Alerts in Indian communities

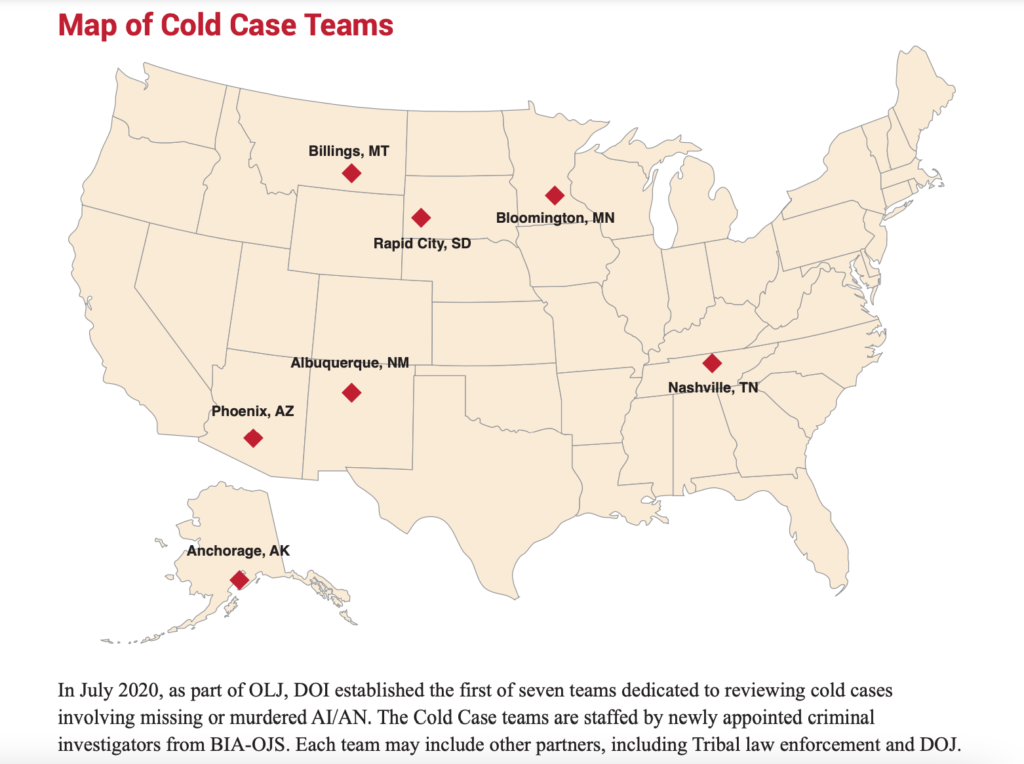

Their focus for this second year of the Task Force, as things stand, is on law enforcement training especially with regard to trauma-informed responses to cases involving missing or murdered American Indians and Alaska Natives; coordinating with state and local law enforcement agencies in areas with large AI/AN populations; assisting Tribal law enforcement agencies with developing formal arrangements with their Federal, State, and local law enforcement partners regarding missing or murdered AI/AN cases; developing a guidebook for families when an adult goes missing on how to engage with and what to expect from law enforcement; and creating a searchable database of resources across DOJ, DOI, and HHS that will assist communities identify training, funding, technical assistance, and other resources.

According to the DOJ, Tribes are taking concerted action to address Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW) issues. “The Yakama Nation in southern Washington began accessing the state’s major violent crime database to track the disappearance of tribal members. On the Navajo Nation, the Missing and Murdered Diné Relatives working group is tackling issues like sex trafficking and child abductions in the nation’s largest Tribal jurisdiction. In Montana, the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes are working with state officials to prioritize cases of missing or murdered Tribal citizens.”

The work is ongoing. For us, though, one comment from a “Listening Session” in June 2020, by Renee Bourque, a citizen of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation stood out: “We need more funding for Tribal communities to have training and education, and the ability and funding to develop their own response which best suits their community needs,” she said. “What works on the Fort Berthold reservation is not going to work within the boundaries of the Muscogee Creek Nation. We have to make sure that we allow our Nations to guide these responses that best suit their needs.”

Please send any feedback to marketing@biometrica.com.