In Search Of The Missing: What To Do, What To Know, And What To Say

With the city of San Francisco waterfront in foreground, a container ship sails on San Francisco Bay with the city of Oakland and Port of Oakland in the background. Mt. Diablo looms over the scene. The Bay Area Search And Rescue Council (BASARC) has quite the task. Photo © Stevehymon | Dreamstime.com

By Kadambari M. Wade

* As of Dec. 31, 2017, the National Criminal Information Center Database or NCIC contained 88,089 active missing person records.

* Agencies added 651,226 missing person records to the NCIC last year, and purged 651,215 records (not necessarily the same) for various reasons. This included when a Law Enforcement agency located a person, or a person returned home.

* As of Dec. 31, 2017, the NCIC also contained 8,634 unidentified person records.

* Agencies entered 886 unidentified person records into the system in 2017 — 674 were deceased unidentified bodies, 5 were unidentified catastrophe victims, and 207 were living persons who were unable to ascertain their identities.

Source: NCIC

Forty-eight hours after we first began this conversation in late July, Christopher S. Young’s Search and Rescue (SAR) team, based in a Northern California county and operating under the jurisdiction of the sheriff’s department there, received a call to be on standby to head to one of California’s giant fires, for logistical support. “What exactly did that mean?” I asked. “Anything the firefighters on the frontline and law enforcement need,” Mr. Young responded. “We’re trained in Search and Rescue, and we’d apply that training, it could mean moving people out of homes, it could mean persuading them, it could mean searches, whatever.”

Mr. Young, the Chairman of the Bay Area Search and Rescue Council (BASARC), is a past reserve captain for the Sheriff’s SAR Team, and a current Level 1 Law Enforcement Reserve Officer with his sheriff’s department and the city he also does patrols for. He has been active in Search and Rescue since 1981. Author, instructor and educator, he is recognized as one of the preeminent authorities on Urban Search and Rescue in the country, and works with different groups within and beyond Law Enforcement on missing person searches across the United States and elsewhere.

But on any typical day, the frontline for his team of searchers is a very different one. It’s not necessarily fiery, but the environment could be dark, smoky, dense, crowded, unfamiliar, hostile, and dotted with any number of pitfalls familiar to anyone who’s ever lived in a large, teeming urban environment.

More densely populated areas, certain areas that have higher crime, or shifting homeless populations, sections that may have people not comfortable with English, others that have people wary of, unresponsive or hostile to anyone in uniform. Then there’s the shifting or changing terrain — there may be an apartment building one minute, a mall the next, an office complex two blocks away, and homes with backyards two streets down. Through all of this, time is of the essence, and every incident is an active situation, where the missing subject’s life is potentially at risk.

In this first of four pieces this September, as we look at public safety over the annual MUPC Month, Mr. Young takes us through the process, the emotion, and all the rest of what is involved in finding a missing person.

A time lapse video of the BART, which served 124.2 million passengers in 2017. For Search and Rescue officers, searching for missing persons in densely populated urban areas, with public transportation and easy travel, is a very complex process. Photo © Sean Fleck | Dreamstime.com

USAR, SAR & Urban Search

Interviewer: Before we begin, while you’ve defined this in your book, “Urban Search: Managing Missing Person Searches in the Urban Environment,” could you define the difference between “Urban Search and Rescue,” and “Urban Search?”

Chris Young: Urban Search and Rescue is USAR, that’s the term FEMA uses and they are really focused on disasters — hurricanes, buildings falling down, floods, and earthquakes. These are usually people from the fire services. FEMA has them scattered across the U.S. In the Bay Area, for instance, they’re in Oakland and Menlo Park, and there’s LA in the south. They are people with specialized training and the equipment to deal with disasters of different kinds. Urban Search is what we do.

When we talk about Search and Rescue or SAR in general, I would put it as the urban world, the wilderness world, and the interface between the two, because there are times we search at the edge of an urban or suburban housing development that backs up to an open space. We have to be able to shift gears and look in both environments. There’s training that goes along with this and its management, but the core tenets of search don’t change. I’d also like to emphasize that we’re dealing with Law Enforcement, who have ultimate responsibility for searches, certainly in the State of California, but that’s not uniform across the United States and certainly not in other countries.

Just to be clear, Urban Search and Rescue is focused on urban disaster management on a mass scale, Search and Rescue could be focused on searches in any environment, and Urban Search is specifically focused on individuals that are missing in an urban environment, which is what you and your teams do.

Yes, that is correct. But we tend to use Search and Rescue (SAR) and Urban Search interchangeably for the purposes of conversation, as we’re focused on Urban Search. We do not use USAR, as that is what FEMA is focused on. We look for people that are lost or disoriented, but it also depends on how you define missing. If someone went off trail, they’re lost, and they may be reported as missing. Take the case of a hunter who hasn’t turned up at camp when he was supposed to. From his perspective, he’s bagged his deer, and is dragging it back to camp. He knows where he is, but it took longer than he thought, so he made a decision to spend the night somewhere and set off again in the morning. His buddies, however, might think he’s missing, presumed lost, so it’s a matter of perspective. In SAR, we have to determine whether they’re lost, disoriented, don’t want to be found, depressed, or suicidal, and also have to prioritize all of this based on a number of things.

So in the case of the hunter, would you have put him down as a low priority case or incident?

No, it may turn out that he has a preexisting heart condition or is diabetic. In that case, if he doesn’t get his medication, he may be down for the count. These are pieces of the puzzle we need to know. In the beginning of a missing person’s search, there’s a sense of urgency. I mention this in my book; it’s called the Urgency Chart. In the wilderness, there are 7-9 different conditions we look at, including the weather, age, and medical conditions. In urban conditions, we look at about 14 factors to decide how many resources to send out and when.

So if you knew the hunter was in his 30s, in great physical shape, had no preexisting condition that was known, and the weather was fine, you wouldn’t be as worried about him as opposed to an older hunter that was a known heart patient.

It doesn’t mean we won’t look for the first hunter immediately — it could mean he’s hurt, but when a decision is made on how many resources need to be applied to a missing person incident and in what time frame, that decision depends on the available data.

Who makes that decision?

It depends on who’s managing the process. Typically, Law Enforcement is the authority having jurisdiction, but if they don’t have the expertise, they bring in the pros, and call in SAR to manage the process. The way it’s set up in some counties like ours, SAR is managed through the sheriff’s department. We also have our own jurisdiction, in the unincorporated areas. So while we may also report to a sheriff’s sergeant, who’s still responsible for it, we’re all working for the same agency, or we may end up working for a nearby city too. In that case, that city’s police department may have overall responsibility, but we manage the process. While it’s a balance, there’s a general understanding on all sides.

You also have a Mutual Aid System within the state and elsewhere.

Yes, within California, but also in other states and countries, where, if someone has exhausted their resources, they’ll call for other resources. For instance, if a local Law Enforcement jurisdiction has exhausted its resources for a missing person search, they’ll call in the local SAR team. When rural counties in the state that use their own peace officers run out of resources, they call the California State Office of Emergency Services (OES) 24×7 number, and say, “We need more help.” The State will then call around to local counties around that county, and say, “Hey, they have a missing person, they need resources.”

In The Heart Of The Fire

I have a question on the recent California fires. In terms of an incident, they would come under USAR, or disaster management, even if not urban. What role, if any, could people like you and your team, with the experience you have in SAR, play in these situations?

We absolutely could and do. We were in the fires in October 2017, and going back, we’ve worked on others, including the Oakland Hills Firestorm in October 1991.

[Editor’s Note: 25 people died, 150 were injured, and 2,843 single-family dwellings and 437 apartments were destroyed in this disaster, officially called the Tunnel Fire].

The actual fighting of the fires is the responsibility of the Fire Service. They will call in specialized services trained in firefighting, and bring in people from other parts of the state and out of state for that. Now Law Enforcement, under which SAR falls, will be called upon to provide security, provide evacuation, go door to door and say, “You need to leave, the fire’s coming.” You try not to use force, but there have been times when you’ve had to say, “You need to leave now or you’re going to die!”

You’ve actually had people resist even when you told them they might die?

Yes, absolutely, and say, “I’m not leaving my home.” Several reasons. Pets, livestock, or they were afraid people would come in and loot their homes. SAR is tasked with going with Law Enforcement and saying, “You need to leave,” when there is a mandatory evacuation order, and provide logistical support. After a fire, SAR is brought in to search residences or what’s left of residences to look for missing persons. In the Oakland Hills fire, more than 2,000 homes were destroyed, there were many missing person reports, and there wasn’t a lot of communication. So we, as in the Bay Area Search and Rescue teams, got together, and were asked by local Law Enforcement, fire, and the State Office of Emergency Services to look for missing people and body parts.

I was part of the management of that, they figured it would take us six-plus weeks; we did it in six days. We used our management and search techniques, and were able to apply that to this type of incident, we used dog resources trained to find human remains, we use planning, and called for the resources we needed.

Who has authority on calling for resources?

It’s a combination of state law, statutes, and who wants to take on the role. You get some rural police departments who may not have any idea on how to go about managing a search and may not be trained or equipped for it. They get a call about a missing person, and say, “I’m going to send my deputies out to look for him,” not even realizing that there are protocols, there are other resources out there…

Doesn’t that potentially put the deputies in danger? When they get sent out without being trained or equipped in Search and Rescue?

Well, for anybody in Law Enforcement, officer safety is always paramount. We don’t want to send them out without knowing what environment we’re sending them into — we have what’s called a safety checklist, whether we’re sending them out into the wilderness, or going into so-called bad neighborhoods, where there’s drug dealing, the homeless, and needles everywhere. When our teams approach homeless encampments, we wear uniforms. Most people in our SAR teams are not sworn reserve officers like I am, so part of the training process is needing to know that if they have a uniform on, they may face a perception from people that are homeless that “these people might be coming to take my stuff.” We train our people to make a lot of noise to let the homeless know they’re coming, to ask for help, and say, “We’re looking for this person, can you help us?” Homeless people can be very helpful in searches, and they have helped us find missing persons.

The Uniform: A Target Or A Talisman?

When you go into some of these high crime areas, is the uniform a good thing or a bad thing? Does it protect you, or is it a target?

I’d have to say both. In Law Enforcement, there’s what’s called a Command Presence — just the fact you walk in, you have a uniform on, you have these things hanging off your belt — people that have a uniform on, whether you’re in Law Enforcement, or the military, even security guards, that typically signifies a sense of command and respect for authority to the general populace.

Now, the sense of what that command presence signifies to a particular section of the populace may differ, it may mean, these are bad guys, or, these are good guys, let’s help them, but there’s always an association. One of the things we teach is when you go into a neighborhood, keep your eyes open, observe, and look around for potential dangers. When you walk up to a house to talk to a resident that might have seen something, note how they have the cars parked, whether they have dogs barking loudly, do they look mean, do you want to go into that yard? Perhaps you don’t. We tell our SAR people, if you don’t feel safe, don’t go in there. We can send people higher up the chain as far as that command presence goes, meaning someone with a badge, a bulletproof vest, a gun, people that would have a better opportunity to protect themselves if something went sideways.

But everyone has some kind of uniform?

Yes, always.

Do you also aways travel in pairs or teams on searches?

Yes, a minimum of two, but usually three of four, whether it’s urban or wilderness, you don’t want to send people out by themselves. We train that way. It’s for safety purposes too, if someone gets hurt, what do you do?

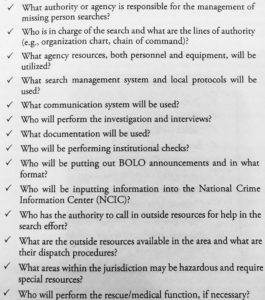

At the beginning of your book, you list 7 basic questions you indicate a search team has to ask.

- Is each missing person actually lost or just avoiding the caregiver?

- What resources would you use to conduct the search?

- Where do you start searching?

- How would you search?

- Would you search at night?

- How long would you search before asking for more help?

- Do you even need to start a search?

- Here’s one more question: How much time do you give yourself to answer those questions, and who takes that call when you have different agencies involved?

It might be easier to talk about a scenario unfolding. Let’s take the case of someone suffering from dementia. Let me clarify here that we use the terms Alzheimer’s and dementia interchangeably, but Alzheimer’s is a form of dementia and not the other way around. Let’s say a family is caring for an elderly father suffering from dementia and they wake up one morning and he’s not in his room. Normally, people would do a basic search, check the bathrooms, check the house, check around the house, and then finally, if they can’t find him, pick up the phone and dial 911. If they are in a campground or something, they’d find a phone, find a ranger and do the same thing. But dialing 911 in our country is pretty standard protocol.

What happens next?

At the end of that phone line, the 911 operator asks a series of questions that are supposed to help make a determination on where to route that call. Suppose the family knows where the father is, but he is down and hurt, the dispatcher will call Fire and Ambulance. If it’s a missing person, then they assign that to whichever jurisdiction has responsibility for where he or she lives.

What about if you’re calling an elderly parent from out of town?

If a family is trying to contact their father from out of town, their calling 911 will get them through to their local 911 operator, who will then contact their local police department. That local department is required to take the report of the missing person, and in turn, contact the police department in the jurisdiction where their father is, ask that police department for what’s called an “Outside Assist,” and ask for a “Welfare Check.” When I’ve been on patrol, I’ve got that call several times: “You need to do a Welfare Check at such and such address,” based on some basic information given by the reporting party. There is decision-making that goes on through this process, and while someone is driving to the residence, it’s possible that you find the missing subject on the road just walking along, and you give him a ride back.

The Devil Is In The Data — And The Details

What information do you need, as part of this decision-making process?

There are two types of information that we in Law Enforcement and SAR want to know about the missing subject. The first is searching or searcher data. In other words, the basic descriptor information on the missing person: What’s their clothing description, height and weight, male, female, etc. Your environment then plays a role; for example, in the wilderness, for instance, if you’re looking for an 8-year-old, you may not need a lot of information other than it’s a missing 8-year-old. To emphasize the difference between a wilderness and an urban environment, I sometimes say this half in jest to my students, that “when you’re in the wilderness and you find more than one 8-year-old, you can bring them back and we can sort them out later!” It isn’t intended to make light of any situation, it’s to teach them that there is a huge difference in the environment, one they need to recognize and pay heed to, by keeping track of the details and the data. In an urban environment, you’ve got lots of 8-year-olds out there, so you need specific information to pick out the one you want.

You have searcher data as the first, what’s the second type of data you need?

Planning data. In search management or Law Enforcement, that’s the information you need to plan the operation looking at scenarios in determining what resources to apply and where to deploy them. We have to be able to assign people based on the history of the person. This guy we’re looking for may like to go to the local 7-Eleven and buy cigarettes, so we would need to look at the their security cameras.

Is this what you’ve referred to as pre-planning?

Pre-planning actually is different. Pre-planning goes back to looking at types of incidents you’ve had before, and using those experiences to plan ahead for similar incidents. Take BART, for example, the Bay Area Rapid Transit. If we suspect a subject has managed to get onto a BART train and gone into San Francisco, one of the things we’d like to do is look at security videos and see if the person went through the pay gates, got off at a platform, and went into the City. Part of the pre-planning is whom do we call at BART? They have their own police department, but who is the contact person there to get access to the video feed, and who is that person at 2 a.m., when BART isn’t running. That’s all planned out and that’s pre-planning, part of inter-agency coordination.

What else goes into pre-planning?

Part of pre-planning is also to do a search of the residents again, even if Law Enforcement has been through there already. We’ve found people, after houses have been ostensibly searched, in attics, in closets, kids in bedsprings even. Search and Rescue teams are trained to search a certain way, and have a set of standard operating procedures that other professionals, even those in Law Enforcement not trained in SAR, may not have. If the person is not in the house, then the local beat cop will go in and get some more information, and get the information out on the streets as soon as possible, then they have to make a call. They can get their own off duty police officers to come in, civilians who work for the police department to drive around, or a SAR team that is in the area. That’s the point where we come in.

By The Ticking Of The Clock: Why Missing Minutes Count

What do you do when someone doesn’t want to be found but is reported as missing? As someone who is both Law Enforcement and SAR, how much of a difference has that Law Enforcement perspective made to your decision-making in cases like these? In addition, can we expand on the categories of missing persons?

Let’s look at why they don’t want to be found first. Part of our investigation, which is what my new book’s focusing on, is what led up to this person going missing. What was going on in their life, minutes, hours, days, weeks, and years up to the point they went missing? The family may not recognize why they’re missing when you get to someone that is “voluntary missing.” Law Enforcement looks at things a little differently than SAR. A missing person, by state and national law, gets filed in a particular category. The person that is missing is classified “at-risk” if they’re very young or very old, has a mental health issue, a preexisting medical condition, or under certain other circumstances. Under those conditions, Law Enforcement has to act within four hours.

Irrespective of whether this individual wants to be missing or not?

Yes, exactly. If someone files a report, Law Enforcement has to act on an at-risk individual’s case within four hours of a report being filed, and get that information into a national database — the National Crime Information Center (NCIC). There’s a subset of that called Missing and Unidentified Persons System (MUPS), you fill in the attributes of that missing person within that. There are serious ramifications if this is not done.

Then you have other categories. Runaway, for instance, which is a very broad category. It may be a child that doesn’t have permission from a parent or guardian to be away. In California, that’s probably 90% of kids that are reported missing. Then it breaks down into “voluntary missing,” like someone that has run away, but for some other reason, not yet ascertained. Then there are “abductions”, parental, relative, or stranger, “disasters,” etc. For us, in SAR, we also have other questions: Is the missing individual a hunter, a fisherman, a hiker (by activity), is he or she a child between the ages of 2-4, 4-6, 6-10 (by age), and other questions like these too.

How would you classify someone like my daughter, who is 9-years old, but about 4 years old developmentally, and also deaf?

She would be among those definitely placed in the most at-risk and vulnerable category. These are children or adults with developmental issues, there may be an age issue, there may be autism, or ADHD, there are upward of 40 categories, based on activity, age, preexisting condition, a separate one for dementia, and a bunch of others. We’d have to talk to you about what signs she understands, what behaviors are typical, or atypical. Robert Koester, who helped me write a chapter in my book on lost person behavior, has written his own book called Lost Person Behavior, and studied thousands of reported missing persons cases on the attributes of lost person behavior, has defined certain traits in this regard.

Could you provide an example?

For instance, individuals with dementia will generally walk in a straight line till they get stuck, then make a slight turn and walk in a straight line till they get stuck again, and then walk in a straight line again, and so on. It’s sometimes referred to as the “pinball effect.” We, as SAR managers, need to understand that Mr. X, a missing gentleman with dementia, is likely to keep going straight in a pattern till he can’t go any further. We may find him 15 miles out of town, just walking. We use that data.

We look for other data too: Is this the anniversary of the death of a loved one that may indicate a possible despondent? It isn’t just one clue, we look for clusters of information, and scenarios. Is someone depressed? Is a gun missing? We need to let our searchers know. Someone may want to take his own life and take someone with him. Or want death by cop. We look at all that. It doesn’t mean we won’t search for someone, it means we need to keep all this in mind, and plan each team’s make-up and our resources accordingly.

Sense, Scent, and Sensitivity

Have you lost any team members?

No, thankfully, not because of SAR situations; however, there are teams in the Bay Area where someone had a heart attack and didn’t survive. There have been other incidents where matters got pretty hairy. Once, a homeowner came out with a shotgun and was waving it around and screaming “get out of my backyard”. His wife was yelling for him to put it down. Fortunately, the team had some good talkers who talked him down. The thing is, if a Law Enforcement Officer had also been on that team, he would have had to draw his gun, and if had raised his gun, and the homeowner hadn’t put his own down, things could have escalated.

How many women do you have?

I’d like to think we’re about 50-50, I haven’t counted, but it’s pretty much around that. I’d say around the western world at least, there are a lot of women in SAR, especially dog handlers. Women seem more dedicated when it comes to training dogs, and they’re great at it.

Is it because the dogs also offer them protection?

No, let’s step back and differentiate a little. Law Enforcement Officers have K-9s. They’re trained to run down suspects, bite when need be, protect their trainer, and search for specific stuff. They work off a different scent, that of people when they’re scared. You definitely don’t want an aggressive dog in SAR. You have dogs like bloodhounds that are trained to follow a specific scent, a piece of cloth, or a sweater. They will work on a leash. Then you have dogs trained to find any live human scent in a wilderness space, or in or under water. They usually work off leash.

What happens when an off-leash dog picks up a scent?

Once they find the scent or the subject, there are signals and they’ll let their handlers know in some way. In these cases, the handler is looking at the body language of the dog — perhaps the dog having his head up, sniffing the air, something that is sometimes referred to as “casting.” There are dogs, like cadaver dogs, which are trained to find human remains. Some dogs are trained to find specific evidence, like guns or bullets, while some of our teams are brought in to find evidence after a crime or an incident. We look for bullets, knives, other crime evidence. Some dogs are cross-trained. You may have to tell these dogs, “find live,” or “find dead,” and give them a specific direction.

We do a lot of public relations and safety events, and we encourage kids to come up and pet our dogs. But part of our investigation is whether a missing subject is afraid of dogs. Are they going to turn around and run, or sit and play? We don’t want a potential catastrophic reaction to a dog. We may want the dog along but we may have to leave it behind.

When the missing person is a child, how do you make the determination on whether to return a child to the environment he or she ran away from, or went missing from?

Again, we work hand in hand with Law Enforcement. Occasionally, these searches turn into crimes, especially if a subject is found and he or she is deceased, and we then have to do a coroner’s report. In some counties, like mine, the Sheriff and the Coroner are the same person. So as a reserve deputy with the Sheriff’s Department, I’m also the deputy sheriff’s coroner and my job, in such cases, is to determine whether this is actually a crime or not. The same thing will hold through when it comes to the circumstances of why this person went missing.

For instance?

Let’s take a hypothetical example: A kid comes home from school. He has an F on his report card. His mother tells him, “When your dad gets home, he’s going to beat the crap out of you.” Poof, the kid vanishes. We have to determine a few things. Was there some child abuse stuff going on here? Was the mother just trying to scare the kid and there’s nothing going on — the kid just overreacted? All this needs to be taken into consideration. Because we’re also Law Enforcement, we do have access to Child Protective Services (CPS). If we do find someone alive and they’re despondent, we can put them under what’s called 5150 of the Welfare and Institutions Code, where we can put them under a 72-hour watch for a mental evaluation.

What happens if it is determined he or she comes from circumstances where there’s child abuse?

We get involved. But it all needs investigation, and the job is made more difficult when a child doesn’t want to be found because he or she doesn’t want to go back to an environment because of fear of punishment, abuse, or anything else. So we have to evaluate that and determine what we need to do once we find the child. Typically, if abuse is suspected, Law Enforcement will take a child into protective custody. As we’re affiliated with the Sheriff’s Department, we’re “mandatory reporters”— in other words, if we see something like child abuse, we have to do something. As most of our searchers are not sworn Law Enforcement, they have to tell someone up the chain of command that they suspect something because of this, this and this. Law Enforcement, though, may already know. There may already have been calls to that house, the beat cop may be aware of other incidents.

What other issues do you face with missing children searches?

We also have to deal with stranger danger. There was a missing Boy Scout some years ago in Utah. They spent days and days looking for him, and he heard them calling for him and knew they were out looking for him. He never came out of the woods because it was instilled in him to never talk to a stranger and he was determined never to break that code, till finally, he just couldn’t deal with the hunger. Some parents will teach kids a safe word. Some will say, “You need to ask what the password is, if someone says mommy sent them.” We need to know that password. That’s not what’s commonly asked of families, but we ask them questions like that, it’s training and standard procedure for us.

America: Dealing With Demographic Development & Diversity

According to the latest Census Bureau data from the 2011-2015 American Community Survey, the foreign-born population, or anyone who is not a U.S. citizen at birth, including those who become U.S. citizens through naturalization, comprised 13.2 percent of the overall U.S. population between 2011-2015. Most of this population resides in what’s called “mostly urban” counties, including California. How do changing demographics and different cultural experiences that may affect attitudes toward Law Enforcement and first responders, affect missing person reports, Urban Search training, and response to situations?

It’s interesting that it’s only 13.2%, because California is much, much higher. Where I work, we recognized that fact — of needing diversity training — years ago, and there’s no difference to how we approach a missing person’s report based on the individual that’s gone missing. The hard part is the community, and the perception of the families that are here, legally or illegally, in first, knowing the process of reporting a person that is missing, second, in getting over the fear of reporting it, and third, getting over the fear that they’re going to be found out in case they’ve done something wrong.

Could you elaborate on this?

With criminals, for instance, a family might not want to report a loved one missing because he has an outstanding warrant for drugs, or they don’t know, and we happen to find out, through investigation, that the guy is wanted for drugs. Now are we going to stop and say, “I’m not going to look for him? “ No. We’ll still look for him. The hard part with the immigrant population, on the other hand, is having them understand that we are here to help and not to arrest them, and that we’re going to apply the resources the same as we would for anyone else that is born American. Some of them come from countries or escaped conflict where Law Enforcement or people in uniforms haven’t always been helpful, or been viewed as being helpful, and it’s important to work with communities to get over that perception.

What do you do if you find someone that has an outstanding warrant?

Usually, Law Enforcement will figure that out before SAR does, and it’s happened, I don’t know how many times, before. Law Enforcement, besides filling in the initial missing person reports, will do the initial background checks, and run individuals for wants and warrants. If something comes back that says, yes, he’s wanted for this, or has an outstanding warrant for this, or has a history of this — say, it’s the third time he’s tried to commit suicide — then someone will probably let us know. Most SAR, unless they’re also Law Enforcement, do not have access to that data, and Law Enforcement can choose to share it with them or not. But we find that typically they will share some of it, because they are associated with them.

What about sharing data that’s for your own protection?

If it’s a violent offense, and someone has a violent past, absolutely — if it’s a drug offense or white-collar crime, not necessarily. We’ll notice upticks in potential suicides depending on how the stock market is doing. The big crash, when the dotcom when dot bomb back in the early 2000s, there was an uptick in suicide attempts in some of the upscale parts of the Bay Area — Marin County, parts of Contra Costa, where people lost everything. Again, it doesn’t change our perspective on how we deal with immigrant populations.

I was also wondering how they deal with you. Many immigrants, as you mentioned, move to the US from countries where Law Enforcement is perceived as the enemy, or corrupt, where people are not used to approaching Law Enforcement, for fear of being treated badly, or brutally.

That is true, and we do actually address that in our training. Part of my training for urban settings is that there are many such families and communities and we need to be culturally sensitive. How do we do that? We train. We go out and bring in resources to train about certain cultures. I have to say we haven’t done a lot of it recently, bringing in outside resources, that is, we’ve kept it more in-house and based it on our own experiences, but we will. It’s all focused on cultural understanding, understanding cultural biases, religious beliefs, and how to communicate, for instance, with first generation immigrants from Asian cultures.

Could you elaborate on that?

Suppose you’re dealing with an elderly Chinese gentleman who can’t speak English, and his grandson is translating. The little kid’s off to the side, speaking. It’s important to know that you’ve got to face the grandfather even while speaking to the kid. You’ve got to give him that respect. So you’re having this conversation with the grandfather as if he understands every word you’re saying.

In some other cultures, eye contact’s a problem. It’s considered an insult if you keep eye contact too long with a woman and you’re a man, and we’ve got to know all this. You have to gaze down. We have to be culturally aware of who our “customers are,” if you want to use a marketing term. It’s important because we’re part of a community, and because of whom we’re working for — we’re working for the Missing Subject.

Is this hard on Law Enforcement Officers and SAR teams?

What do you mean by that?

Does it complicate things — needing to keep multicultural sensitivities in mind, while you’re trying to do the basic job of responding to a live or active situation and trying to potentially save someone’s life?

If you’ve never been exposed to a diverse population, it is hard. But the way we deal with it is, we train our people in what to expect. The first encounter might be somewhat awkward — you can train people as much as you want, but when you actually put someone in a real life situation, it’s invariably different. It isn’t quite textbook or practice. But you put teams together that have seasoned veterans with newbies, so they can learn. This also goes back to pre-planning, on what you can expect from your environment.

What would you do if your search focused on part of a county that had a large population that wasn’t comfortable with English? Does that happen?

Could we be searching in part of a county where a majority of the population didn’t speak English? Yes. They may all speak Vietnamese. We would need a translator or change our tactics. We may not be able to ask the local population for help, or we may use technologies, say, reverse 911, or Community Alert Networks (CAN), or some kind of Emergency Telephone Notification Systems (ETNS), they all come by different names. We can put out alerts in the geographic area with a prerecorded message in different languages, saying something like, “The Office of the Sheriff is looking for a Missing Subject. Here’s what they look like, if you see them, please call this number.”

What kind of system do you use?

There are a lot of chemical plants and refineries in our county and we actually use their system. They use it to report whenever something chemical is coming out a plant, to tell people not to go out for a while. We use it for alerts like these or others. That’s how we can get the word out. It would not change our actual response, other than we may have additional challenges related to culture or language.

Ask, And You Might Receive … Information

We touched upon this slightly but just to expand a bit, how do you deal with missing individuals in areas like the Bay Area, where homelessness is also high? How do you know who is missing? What are some of the issues and challenges specific to the area?

There are some of the same issues with the homeless population, whether in encampments or the homeless on the street. Downtown San Francisco has exploded. It’s hard to walk anywhere in San Francisco. In my real job, managing construction projects, I have to walk all over town. I’m walking and stepping over needles, the homeless sleeping on the streets. Do we want to talk to those people or do we want to avoid those people? We tell our searchers, do your best to talk to them, assuming they respond, because they have those same perceptions — a uniform equals bad guy.

But you have to reach out?

They may have seen something. They may have seen the older gentleman with Alzheimer’s. He may be someone that walks by a couple of times a day. He may have had breakfast with the guys in the homeless encampment, who knows? These may be what are called “unknown witnesses,” people who may have seen something, but don’t know that what they’ve seen is important to an investigation, because the person they saw doesn’t look out of place, doesn’t look abnormal, they just walked by — so we do want to talk to those people.

What about someone that is homeless and missing?

We, as SAR, will not get involved with those searches. That usually falls under pure Law Enforcement. If someone is a missing person, presumed homeless, living in San Francisco, we wouldn’t even know where to start looking for someone like that.

Training, Terrain, Tools, and Tech

When people think of urban environments, they simply think “urban,” but it’s not simply that. You have urban, suburban, retirement communities, educational campuses, government and military facilities, construction sites, office complexes, malls, industrial complexes, urban parks and recreational facilities like sports stadiums, transportation systems, and any number of mixed use developments. Urban Search is a complex, convoluted painstaking process and a time sensitive one, as always.

Two parts to this question: A) What do you look at when you look at this terrain and B) How has technology helped?

Terrain, as such, is very broad. In the urban environment I described in my book, I outlined all that you mentioned simply because when people think urban, they think housing developments and cul-de-sacs, or open spaces and little parks. Or they think of downtown cities like San Francisco. The reason I described some of the rest was because you have any number of micro-pieces in there. Like shopping malls. A shopping mall is its own little environment: You have open walkways between different stores, you have the stores themselves, you have cinema halls and food courts. Universities have hallways, plazas, classrooms, cafeterias, laboratories, workshops, theaters, stadiums, clinics, and that’s a different thing too.

A campsite in Yosemite, where you have all these tents and people with campers, that’s actually a small urban community. People come from urban communities to get away, and then they end up getting into a more compact urban community in a campground, it’s kind of an oxymoron. All these are environments in which SAR skills are trained to adapt to, to look in, out, under and around in, and talk to people in those environments in — Urban Search personnel are specifically trained to look in more densely populated environments. You’re trained to not just look twice at a storefront where someone else may just walk by. You’re trained to notice that the missing subject may be there, leaning over a counter or sitting down behind someone. Details matter. The SAR team would look twice, go in there, walk in and come out. That comes from training. In many wilderness environments, and fields, and golf courses, unless someone is lying down because they can’t physically get up, or is hiding, searches, at one level, are easier to conduct.

Urban environments do seem to make things harder because of the density of population and density of structures.

Exactly. Getting back to the technology side of things, we make use of all available tech. We do cell phone tracking, research surveillance video, put airborne units like helicopters out. Each has efficient and inefficient attributes. Let’s take helicopters vs. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAV) or drones. Helicopters are really good; they have cameras and observers, but are restricted in the air space they can fly over, and how low they can go. But we can use them for transportation, getting people out on the field, and for rescue and recovery.

And UAVs?

UAVs have some of the same attributes as helicopters, they can get up high and look down, fly lower, record what they see and transmit it. They are limited by battery life — 15 to 20 minutes — and limited by law, in that whoever is flying one has to be in visual contact with the drone. Do note, I use drone and UAV interchangeably but UAV is the correct term — if it gets out of sight, he or she has to push a button to make sure it returns to home and most that we use are set up to do that by GPS. But there are concerns regarding privacy, and some states aren’t using them.

You are, though.

We’ve been using them in California for a while and our county just adopted usage, but there’s training that goes along with it. You have to have an FAA Remote Pilot’s license to fly the UAV, but you also have to be trained to spot what you’re looking for. When you’re flying over somebody, depending on how the camera is tilted, you’re looking down on somebody. When you’re looking down, you can’t see everything about that person. I’m easy to find because I have white hair, my kids laugh about it. But if the person has dark hair, it ‘s going to take training to find them in a crowd. That’s a new technology and we’re still learning how to use it.

What’s your basic view on technology coming into SAR?

I’m all for it, I think it’s exciting. I also think it’s important to realize technology is a tool, if you don’t understand why you’re using a tool, there’s no point in using it. I’m a firm believer in that you need to know how to do something by hand before you can understand how you can use technology. It’s like math, you need to know basic arithmetic before you can use Excel. Excel is actually a good example: It’s an extremely powerful piece of software. Most people use it as an extremely basic data collection spreadsheet. They simply don’t use all the functions of excel or mine the data out of it. The other thing about tech sometimes, is that if it becomes so complicated that only one person with a PhD in Computer Science can use it, and if he’s not on your search team, you can’t use that tech, there’s no point to it. It’s got to be simple. I’m a firm believer in advancing technology, being open to anything that will help is essential, but a bigger believer in understanding why a certain resource has to be applied somewhere and how it helps maintain efficiency.

Conversation Matters, Communities Matter

Collaboration in a missing person investigation is paramount. What do you believe to be the most critical element of the Public Safety-Emergency Responder relationship? What happens when an incident crosses county or state lines? Time still remains essential.

You have to collaborate. It’s as basic as that.

Who reaches out first?

We, as Search and Rescue, always try and reach out to the other agency. We say, “Hey, we’re here, this is what we can do for you, these are the resources we have, here’s how we can apply them, please call us early.”

So the most critical element is communication? How important is communicating with the public, and at what stage does communication with the public become paramount?

Yes, communication is absolutely the most critical element of any operation, within our own group and beyond it. We’ll draft up a map, color it all in, and tell our searchers, “Here’s a description, search for 25 feet on either side of that.” When they come back, we’ll ask them what they saw, where did they go, where did they not go, and why?

What comes next?

The intelligence gathering part, and dealing with Law Enforcement Officers on that, and after that, general public communications. The reason we want to communicate with the public at large is so they can help us find missing persons. I wrote in my 1st book about what I called Cooke’s Law.

“The larger the population, the greater the chance

that someone other than the SAR Team or

Law Enforcement will find the missing subject.”

But this is only true if the general public knows we are looking for someone. We have contacts with the local media, through the Department Public Information Officer, and the more information we get out, the more the chance we have of finding someone.

It does depend on the situation, though — what happens in, say, an abduction? If a child has been kidnapped, and the abductor has sent a message saying, “Do not make this public,” how and when is a call made to not do so or to do so? Could you also expand on the use of child abduction alert systems?

Abductions are different. That doesn’t happen only with child abduction cases, it could be a missing adult, it could be a prominent member of a community that is missing. But when it comes to missing children, let me cite some statistics. In California, roughly 80-90% of missing children are considered runaways. You start going down the categories of parental abductions, stranger abductions, etc. Of the roughly 100,000 kids reported missing every year here — and these numbers are going down and are in the vicinity of about 80,000, primarily because of advanced communication as every kid has a cell phone now — 1,000 or so are related to parental abductions. Twenty to 30 cases are related to stranger abductions. In percentage terms, that’s a very small percentage of the 80-100,000 reported missing. However, because of perception, when the mother of a 4-year-old at a soccer game turns around and the kid’s gone, what’s the first thought? Kidnapping.

For most parents, even if your 4-year-old is missing for a few seconds, you’re going to imagine the worst in those few seconds and think of calling the cops, even if your little girl, or boy, has simply run down the field to play with someone else. It’s a natural reaction. © Ievgen Tytarenko | Dreamstime.com

Universal thought — for every parent. I’ve been there, done that. Statistically, however, a very small percentage of children are actually abducted by strangers. A child may have wandered down two or three games down that soccer field and be found playing with another child. But people may want to activate the AMBER Alert system. However, in California and other states, there’s a very strict and narrow criterion to activate the alert and there’s a reason for that. The narrowness is focused on specific factors: If it’s a known abduction, and there’s knowledge of the vehicle, and there’s real worry about the welfare of the child.

Who makes that call on the AMBER Alert?

There’s only one agency that has jurisdiction over the AMBER Alert in California — the California Highway Patrol, so we’d have to contact them. It differs from state to state. They’d look through their criteria and if it doesn’t meet A-Z, they won’t activate it. But if you tell that to the parent of a missing child, they’d go nuts. We understand the AMBER Alert logic, but we can’t always tell a parent that, so we use whatever means we can — the resources at our disposal — to get the word out. You also don’t want the AMBER Alert to become a blind spot, desensitizing the general public to these alerts.

Do you check the backgrounds of people that volunteer to find missing kids?

Anyone that is actually on Search and Rescue teams with us in California has to go through background checks, interviews, training and a probation period. Everyone who volunteers isn’t necessarily cut out for this. Some people are motivated for reasons that are not apparent. In an advertised event, like if there’s a media announcement that we’re looking for Mr. X, a dementia patient, people will come out to help, these are people we call spontaneous or emergent volunteers. Do we use them? We will give them something to do, but not integrate them in our teams. On very rare occasions, that might occur, but generally not in California.

What happens in other states?

Some states rely heavily on convergent volunteers for all searches, and will advertise for volunteers just ahead of a search. I think that is a huge liability that agency is taking on, bringing in all those people, because you don’t have time to run background checks on everyone. You will, however, want to at least take their identification. If they refuse to provide ID, your “spidey” sense should be going off in all directions and you should be saying, “Hey, why not! What’s the reason?” Don’t use them.

Have you had incidents where an abductor has been part of a search?

Yes, we have had incidents where an abductor has interjected himself in a search for a missing child and posed a problem. Usually, though, those searches have been going on at two levels — the organized search, with SAR/Law Enforcement teams, and the unorganized search, where the community has come together and some person, typically a family member or a friend, has organized people into groups. It is an issue in any case, because even with the best of intentions, they may not be trained at all, may not have the right clothing, or may be inadvertently destroying evidence, but we can’t physically or otherwise stop them. We have to keep an eye on them. We tell them that if you see something, don’t take action, call, unless it is life threatening and there’s no time. We try and direct the public as best as we can, and get the word out.

The MUPC & SAR: Today, Tomorrow & Beyond

For the last two years, you’ve presented at the National Criminal Justice Training Center’s Annual Missing and Unidentified Persons Conference (MUPC). As the conference was once traditionally geared toward Law Enforcement, how do you see it in supporting or advancing Search and Rescue training and/or practice?

The first one I went to was with the National Association for Search and Rescue or NASAR. It made sense because we’re dealing with missing and unidentified persons, mostly on the missing side. At my first experience, I did a pre-conference, an urban search management course, and the instructors’ course that goes along with it the next day. Last year, I presented on how Volunteer Search and Rescue and Law Enforcement can work together. Many believe that the conference is directed at Law Enforcement, but NCJTC has been working with organizations such as mine, as well as its other partners, to expand the participation to all agencies, organizations, and individuals who play an integral role and have an important stake in the search and recovery of missing persons.

What do you think about the conference moving west?

I think the fact that the MUPC is moving next year to Las Vegas will allow them to get more people, people who are already familiar with the conference, and many more people who weren’t able to go previously, and help them learn and train. I think it’s great because the community needs this conference.

Finally, it’s exciting to hear you’re in the final stages of your second book. Could you talk a little but about your upcoming book and why you’re writing it?

I wrote the first book because Law Enforcement doesn’t always understand the motivation for SAR professionals to be able to do their job and how to do it — I thought this would help. The motivation for the second book is intelligence gathering. You don’t know what you don’t know, so this is about what you need to know, and how you go about knowing it. It’s a work in progress, and the current working title is “Search Intelligence: The Art and Science of Gathering Information and Building Profiles of Missing Subjects.”

I’ve taken out one of the chapters of my current book and expanded it into its own book. The book is designed for Law Enforcement, Search and Rescue managers, Technicians, Trainers and others. It defines what intelligence and information we need to gather regarding a missing person in the early stages of the search. It starts with the classic face-to-face interview with persons that have first-hand knowledge of the missing subject. This includes who should be doing the interviews, the interview setting, and the basic information needed to develop searching and planning data. It then discusses the variations of gathering first-hand knowledge through the use of telephone or remote interviewing, field interviews of persons on the street or trails, neighborhood door-to-door canvassing as well as post-search interviews of the missing subject.

It then goes into investigational tools and other sources of information, such as mining information from social media, crowdsourcing of surveillance system videos and photographs, cellphone forensics, and other technology tools, both currently available and our hope from the near future.

A Note About This Series

Running from mid-September to Oct. 1, the one-year anniversary of the Las Vegas shooting, this is a four-part series in lieu of the Missing & Unidentified Persons Conference (MUPC), which is skipping a year as it moves to Vegas for its 12th edition next year. Each piece features an expert and focuses on an aspect of law enforcement and other public safety response to missing persons and mass casualty incidents: Urban Search and Rescue; Forensic Imaging in Missing Children Cases; Investigations focused on At-Risk Communities, Including Human Trafficking; And Mass Violence and Terrorism. This is the first of the four. The second piece will run on Monday, September 24. This series is a collaboration between the National Criminal Justice Training Center (NCJTC) and Biometrica. You can register for the 2019 MUPC here.

You can email the writer at kmurali@biometrica.com