An Odyssey: Tracking The Sex Offenders That Live Among Us & Securing Our Communities

This artwork, in the image of 8-year-old Ryan VanLuchene doing what he loved best, being outdoors, was created especially for us by Germany-based Indian photographer and artist, Priyanka Oberoi. Her work can be found here.

By Derek VanLuchene, with Nadia Eley

On August 31, 1987, the last day of summer that year, 8-year-old Ryan VanLuchene went out into his backyard in a rural Montana town. Ryan loved the outdoors. On this particular day, he went down to play by the creek that ran behind the family home, to catch minnows. Little did he or anyone else know, that on that last day of the summer break, more than 30 years ago, the unthinkable would happen. Ryan disappeared — right from his backyard.

Thinking that Ryan had simply wandered off, or chased butterflies too far into the woods, Ryan’s family began to search for him. After an hour or so of looking for him, his mother knew something was wrong and called the police. The police believed there was little to worry about despite his mother’s call for help, because they too assumed that Ryan had “just gotten lost,” and wasn’t “really missing.” In fact, an officer was not sent to the VanLuchene home until six hours after Ryan was reported missing, because nothing like this ever happened in this small Montana town.

The search for Ryan lasted throughout the night and well into the next day, with no clues forthcoming, nor a sign of Ryan. Meanwhile, a probation officer, who heard the missing child bulletin on the radio, had a very bad feeling. He knew that in the same community, a dangerous, repeat sex offender had been released from state prison not even 90 days before Ryan went missing. Thinking the unthinkable, the probation officer and law enforcement found the individual and questioned him about Ryan’s disappearance. Through this process, they found evidence that connected him to Ryan. Eventually and tragically, this unsupervised repeat child molester led them to Ryan’s lifeless body, changing the course of the VanLuchene family forever. (From RyanUnited.Org)

“On August 31, 1987, my life changed forever.

My 8-year-old brother Ryan was abducted from our family’s backyard and murdered by a repeat sex offender.

I was just 17-years-old when Ryan disappeared.

Since then, my family and I have dedicated our lives to honoring Ryan’s memory. I have dedicated my career to sex offender management and child abduction response. In 2003, I founded Ryan United, a nonprofit

organization dedicated to providing training to

law enforcement and communities.”

[Editor’s Note: Derek VanLuchene brings both personal and professional experience to missing person investigations. In addition to serving as President and Founder of Ryan United, he also served 18 years as a Montana Law Enforcement Officer working for both the Conrad Police Department and the Montana Division of Criminal Investigation. In his current role as Project Coordinator for the NCJTC, Derek remains steadfast in his efforts to protect children.

Today, we take a closer look at missing person cases from the perspective of a family member, and examine the progress that we have made and how far we still must go. Derek writes this piece with his National Criminal Justice Training Center colleague and the 2019 Missing & Unidentified Persons Conference Event Coordinator, Nadia Eley, JD].

The Missing Person Investigation

Over 600,000 people go missing each year (NamUs). The sheer number of missing person reports annually indicates that this problem has become the nation’s silent mass disaster — a national epidemic (NIJ). In a June 2018 conversation with Biometrica, Caroline Humer, the Director of the Global Missing Children’s Center at ICMEC, the International Centre for Missing & Exploited Children, highlighted the challenges to prevent child abductions, including the absence of a clear definition of missing persons, and the lack of comprehensive, usable data. The bottom line is that there is no true measure about how big this problem is, even though everyone is aware that it is a problem of epidemic proportions.

Existing data suggests, however, that in many instances the missing individual returns home safely. Unfortunately, there remain missing person cases that go unresolved or result in tragic circumstances, resulting in more long-term investigations and cold cases, and ongoing trauma for the family and community.

“Ryan’s case was rare [less than 1% of all abductions

are stranger abductions that result in murder], but

others had suffered in similar ways, either through

having a missing child, or having a loved one suffer through the horrible crime of sexual assault.”

As we have learned in Ryan’s case and in many others, missing person investigations are complex and multilayered. Many present “rare” or varied circumstances, with some more difficult to solve than others. In fact, as reflected in NCIC data, missing person cases often include circumstances that go beyond abduction. This includes any individual whose whereabouts are unknown, whether it be voluntary or involuntary, the result of a mass casualty or catastrophic event, or other circumstances that have caused that individual to leave their families, homes, or communities, such as a transient lifestyle, mental or physical disability, etc. In all cases, no matter the circumstance, the threat of possible danger warrants an expeditious yet thorough approach to investigation.

Though many of the same investigative strategies and tactics are widely used, departmental resources, time of reporting, the cause of disappearance, and many other factors play a part in determining solvability and response. As an example, in mass casualty incidents, the urgency of safely securing the scene and providing aid may cause some delay in the identification and recovery of victims. In cases involving homicide or other crimes, the investigative process that is dedicated to identifying the suspect of the crime runs parallel to the search and investigation of the missing person.

In at-risk and vulnerable missing person cases, communication barriers or elopement may present challenges to the search team and investigator. Some individuals may evade the police, even when their name is called; or, hide or seek shelter in enclosed areas that prevent search teams from finding them. For those responsible for the search and rescue, a lack of knowledge or training on how to communicate effectively with and safely locate a person with a disability, or language barriers or a fear of police may adversely affect the recovery and outcome.

[Editor’s Note: You can see more on this last in our first piece in this series on SAR here]

The Road To Nowhere

- Approximately 1 out of every 59 children has been identified with Autism Spectrum Disorder. According to the National Autism Association, “nearly half of children with autism engage in wandering behavior. More than one third of children with autism who wander/elope are never or rarely able to communicate their name, address, or phone number.”

- The Alzheimer’s Association reports, “6 in 10 people with dementia will wander. A person with Alzheimer’s may not remember his or her name or address, and can become disoriented, even in familiar places.”

- According to the FBI, there are more than 7,700 American Indian children listed as missing in the United States.

- In Washington State, Native Americans make up less than 2 percent of the population, but represent more than 5 percent of the missing persons cases.

- The National Institute of Justice reports that more than 56% of American Indian and Alaska Native women experience sexual violence in their lifetimes.

According to a 2017 NCIC report, 33,896 persons (out of 651,226) were entered as a missing person with a mental or physical disability.

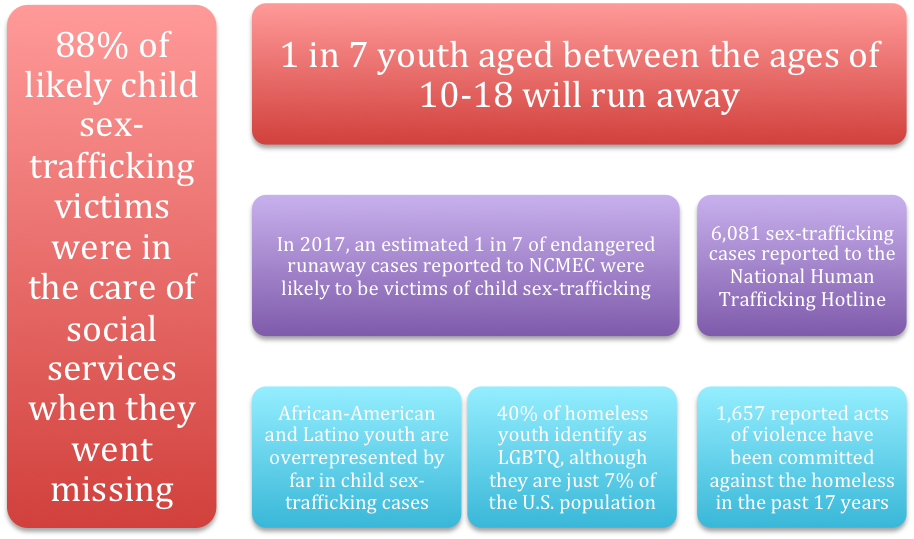

Perceived voluntary disappearances, such as those involving runaway and homeless youth, or even missing adults with substance abuse disorders or life-changing circumstances, may cause delays in reporting to the authorities and ultimately, investigative hurdles for responding jurisdictions.

The hard truth is that children living on the street are vulnerable to recruitment and exploitation by traffickers and other perpetrators who intend to harm them. In fact, research suggests that traffickers approach youth living on the street within 48 hours of running away.

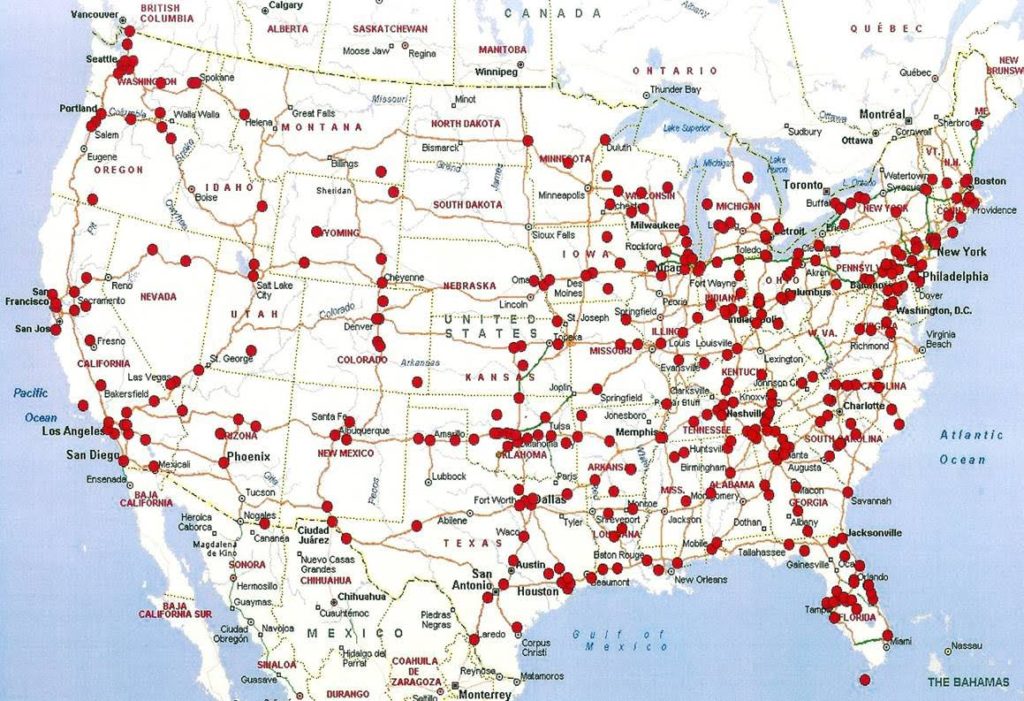

Many children run away or are lured away from home due to factors in their home, school, or community-related environment, such as poverty, abuse, neglect, alcohol or substance abuse. Ultimately, these factors contribute to a cycle of abuse and create opportunities for coercion or exploitation in exchange for food, shelter, the feeling of belonging, or love. Hotels or motels, densely populated areas, and truck stops are common venues for this crime making it almost undetectable, and the victim’s whereabouts unknown to their families and community.

Similarly, homeless adults are at risk for violence and victimization. In 2015, the MUPC conference provided a case study of the disappearance and murder of 19 year-old Casey Jo Pipestem, a Native American from the Seminole Tribe. Police believe Casey Jo was murdered in January 2004 after being abducted from an Oklahoma City truck stop. Her disappearance was believed to have been tied to a number of serial murders in the Midwest. This in turn led to the development of the FBI’s Highway Serial Killer Initiative, which was designed to raise awareness among law enforcement agencies, truck drivers, and the general public about the murders.

The disappearance and murders of adults and minors, males and females, persons of various ethnicities, many presumably high risk due to transient or alternative lifestyles, demonstrate the unconventional nature of missing person cases and that not all disappearances should be investigated in the same manner. It is often cases like Ryan’s and Casey Jo’s that promote awareness and opportunities for the field to improve its responses through training, collaboration, and coordination.

By The Ticking Of The Clock

When individuals are missing, time is the enemy. The initial hours are the most critical for reducing injury to the missing person, safely locating them, and minimizing any resulting trauma to the missing person, their family, and the community. A timely response is key to obtaining critical information and details about their actions and common behaviors, the last known location, figuring out whether a crime was involved, and gaining an insight into the identities of any suspects.

“When my brother was abducted, the responding

agency spent lots of time trying to get resources

together. During this type of investigation, all

effort should be focused on locating the child,

and not on obtaining resources.”

Preparedness is a crucial component of timeliness in any missing person investigation. It is critical that responding agencies know what their resources are and how to access them BEFORE they receive a missing person report. Whether through training or resources inventories, knowledge of all possible tools and resources — including forensic, geospatial and surveillance technology, telecommunications and social media — are a key to developing and more rapidly deploying investigative strategies.

“Any extra time spent securing resources is time wasted. Every minute counts.

Furthermore, the search and investigation of any missing person is not one that should be undertaken alone. Rather, collaboration and the leveraging of all possible resources promotes successful outcomes and case closures. Identifying and developing partnerships with local search and rescue (SAR) partners, neighboring law enforcement jurisdictions, human trafficking task forces, probation and parole, and/or the media in advance, can minimize any investigative hurdles in navigating jurisdictional boundaries and assigning manpower and resources to the investigation.

“So much has changed since my family

faced the unthinkable in 1987.”

Despite the common challenges in any missing person investigation, there is hope for the missing and their families. Today’s missing person data, training, and information are more inclusive of all missing persons — children and adults — and the various circumstances behind missing person reports. The evolution of technology and training has increased our ability to respond to missing person reports, identify suspects, provide public notification, and more importantly, provide a swift and coordinated response.

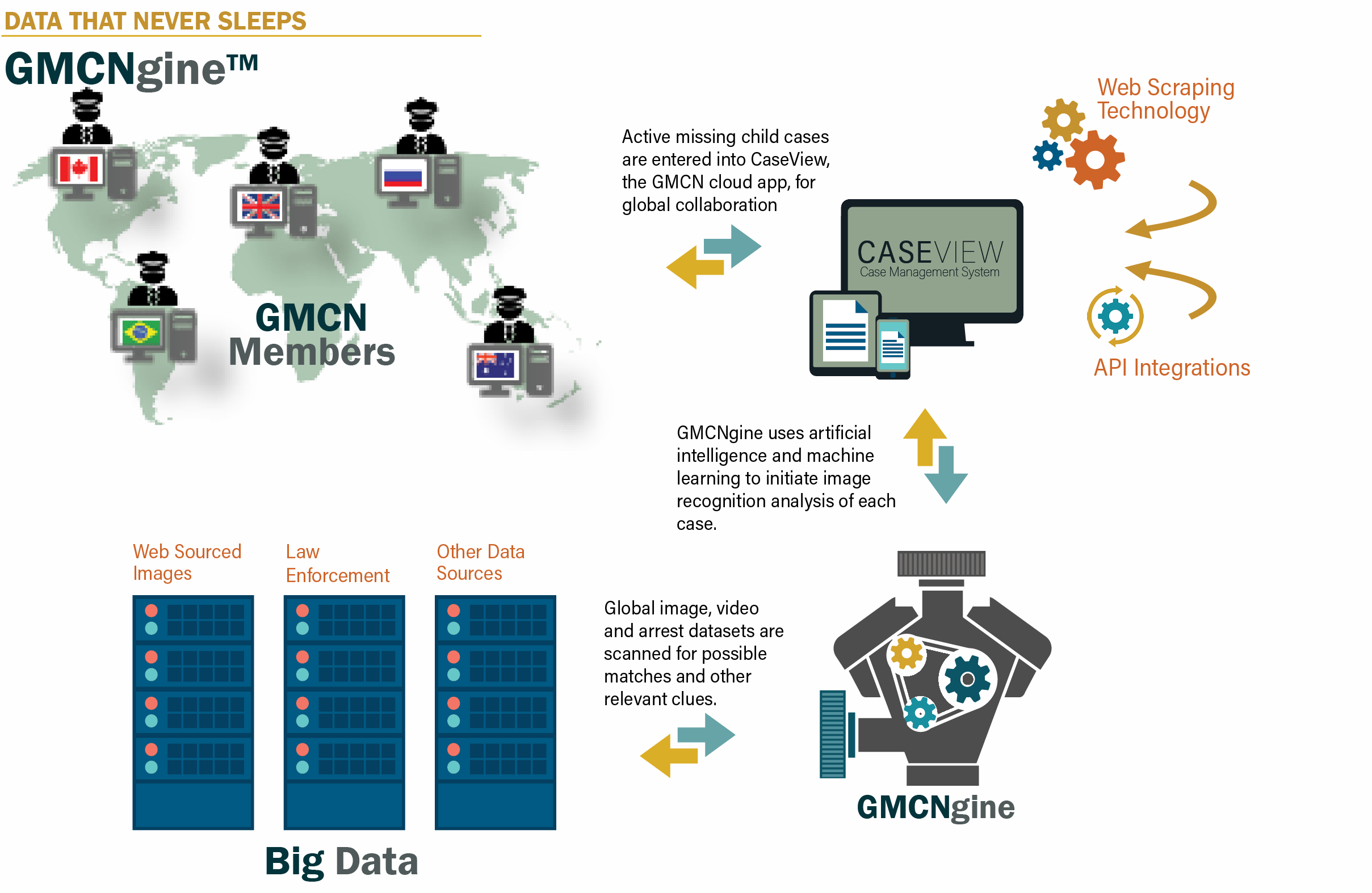

State and federally sponsored endangered or missing person advisories, like New York’s Vulnerable Adult Alert Program, the AMBER Alert, Silver Alert, Green Alert, Virginia’s Ashanti Alert, and others provide tools and strategies for a more effective collaboration and communication to facilitate the rapid deployment of information. Technological advances in forensic imaging and reconstruction, DNA phenotyping and genealogy, have increased the solvability of long-term and cold cases. Facial recognition software, social media, cell phone data, app technology and online investigative techniques are used to identify and safely locate victims of exploitation and trafficking.

These and other tools demonstrate our heightened awareness of missing person cases and vulnerabilities, our ability to investigate missing person reports with greater precision, and our collective dedication to ensuring the safety of all no matter the circumstance. But, as a family member who has faced this tragedy head on, I know there are still more groundwork to be covered until all missing persons return home safely. This is our collective challenge.

“Despite how far we’ve come in technology and training, it is crucial that those in the field are continually expanding their knowledge of the dynamics involved

in these rare and complex cases. While every

missing person case will most likely not be the

worst-case scenario, it is crucial that we are prepared

for that worst-case scenario.”

[This piece is courtesy Derek VanLuchene and Nadia Eley, JD, of the National Criminal Justice Training Center (NCJTC) of Fox Valley Technical College. For more than 25 years, the NCJTC has provided national training and technical assistance to agencies, organizations, and individuals in the criminal justice field, to help solve the most pressing public safety needs. Through its National Conference on Responding to Missing & Unidentified Persons (MUPC), the NCJTC offers innovative approaches, techniques, and technologies to more effectively investigate the tragic circumstances surrounding missing person reports.]

A Note About This Series

Running from mid-September to Oct. 1, the one-year anniversary of the Las Vegas shooting, this is a four-part series in lieu of the Missing & Unidentified Persons Conference, which is skipping a year as it moves to Vegas for its 12th edition next year. Each piece features an expert and focuses on an aspect of law enforcement and other public safety response to missing persons and mass casualty incidents: Urban Search and Rescue; Forensic Imaging in Missing Children Cases; Investigations focused on At-Risk Communities, Including Human Trafficking; And Mass Violence and Terrorism. This is the second of the four. The third piece will run on Saturday, September 29. This series is a collaboration between the NCJTC and Biometrica Systems, Inc. You can register for the 2019 MUPC here.

You can email any questions to media@biometrica.com