Runaways And Homeless Youth: Alone, At Risk, And Scared

By Deepti Govind

One in 10 people aged 18–25 and one in 30 people aged 13–17 experience homelessness each year. To put it another way, in a classroom of 30 students, at least one will experience homelessness this year, which means they won’t have a safe living environment to call home and will be forced to couch-surf, bounce around among relatives and friends, live in shelters, or stay on the streets, according to the National Runaway Hotline’s 2020 Crisis Services & Prevention Report.

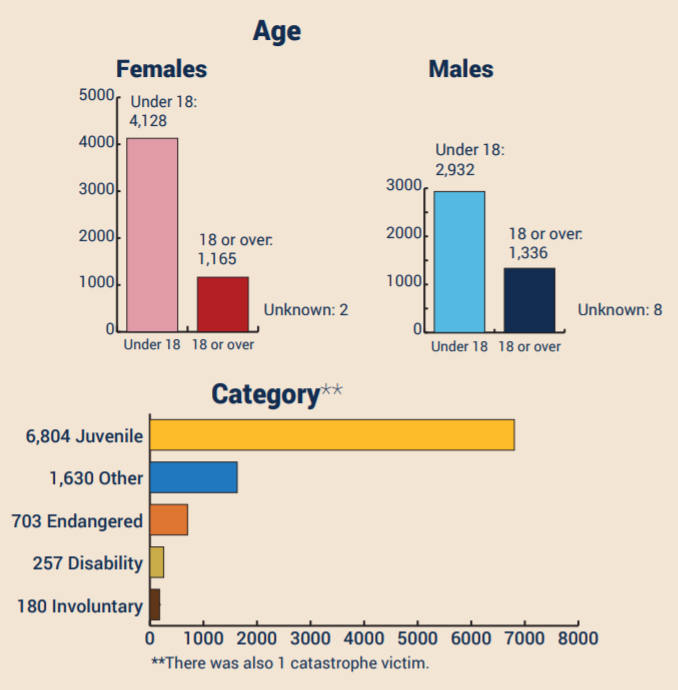

As of December 31, 2020, the National Crime Information Center (NCIC) contained 89,637 active missing person records. Juveniles under the age of 18 account for 30,396 (34%) of the records and 38,869 (43%) of the records, when “juveniles” are defined as those under 21 years of age. The Missing Person Circumstances (MPC) field is optional and has been available since July 1999 when the NCIC 2000 upgrade became operational.

Of the 543,018 records entered in 2020, the MPC field was utilized in 259,802 records (or 48%). Within those records, 246,310 (or 94.8%) were coded as runaway, 1% as abducted by non-custodial parent, 0.11% as abducted by stranger, and 4.09% as adult–federally required entry. Further, when it comes to missing Indigenous Persons, there were 9,575 total missing American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) person entries in 2020 and 1,496 end-of-year active records, according to the NCIC. Of the total AI/AN missing person entries, close to 75% were for individuals under the age of 18.

According to the National Human Trafficking Hotline, which maintains datasets on the issue of human trafficking in the United States, of the 11,500 cases reported in 2019, 2,582 involved minors. The data is non-cumulative and cases may involve multiple victims, and the latest period for which data is available is for the year 2019.

Why is homelessness among the young a crisis that goes much beyond them having a place to call home, and one that becomes a matter of public safety? Because homelessness puts youth at risk for several negative outcomes, ranging from struggles to find consistent food to mental, emotional, and physical health issues, and even physical and sexual abuse, substance use, and premature death. In many cases, these young people land up in situations similar to the very ones that drove them to run away in the first place. For instance, some who run away from homes where they face physical or sexual abuse may find themselves stuck with another person, or a trafficking ring, that inflicts the same horrors on them all over again.

In the next section of this piece, we examine definitions related to runaways and homeless youth and the intersection between the two with darker, more insidious activities like sexual abuse and trafficking.

To start off with, when exactly is a child or a young adult considered to be a runaway? And are there different definitions for children who go missing under different circumstances? The International Centre for Missing and Exploited Children’s (ICMEC) Global Model Missing Child Framework says a “missing child” is any person under the age of 18 whose whereabouts are unknown. There are many different types of missing children cases and each category requires a different, yet immediate response, it adds. According to that framework, the categories and their definitions are:

- Endangered runaways — The ICMEC defines endangered runaways as a child who is away from home without the permission of their parent(s) or legal guardian(s). The NCIC’s Missing Person File further adds that endangered runaways are those who are missing under circumstances indicating that they may be in physical danger.

- Family abduction — The taking, retention, or concealment of a child or children by a parent, other family member, custodian, or their agent, in derogation of the custody rights, including visitation rights, of another parent or family member fall under this category.

- Non-family abduction — The coerced and unauthorized taking of a child by someone other than a family member is called non-family abduction.

- Lost, injured, or otherwise missing — Per this definition, facts are insufficient to determine the cause of a child’s disappearance.

- Abandoned or unaccompanied minor — A child not accompanied by an adult legally responsible for them, including those travelling alone without custodial permission, those separated by an emergency, those in a refugee situation, and those who have been abandoned or otherwise left without any adult care come under this definition.

According to the National Incidence Studies of Missing, Abducted, Runaway, and Thrownaway Children (NISMART), a runaway episode is classified as one that meets any of the below criteria:

- A child that leaves home without permission and stays away overnight.

- A child 14 years old or younger (or older and with intellectual or developmental disorders) who is away from home, and chooses not to come home when expected to, and stays away overnight.

- A child 15 years old or older who is away from home chooses not to come home and stays away two nights.

A thrownaway episode is one that meets either of the following criteria:

- When a child is asked or told to leave home by a parent or other household adult, no adequate alternative care is arranged for the child by a household adult, and the child is out of the household overnight.

- When a child who is away from home is prevented from returning home by a parent or other household adult, no adequate alternative care is arranged for the child by a household adult, and the child is out of the household overnight.

The same NISMART report, published in 2002, also states: “In the literature on missing children, runaways have sometimes been referred to as the ‘voluntary missing,’ to distinguish them from abducted and lost children. However, this term misstates the nature and complexity of the problem. It is generally recognized that children who leave home prematurely often do so as a result of intense family conflict or even physical, sexual, or psychological abuse. Children may leave to protect themselves or because they are no longer wanted in the home. The term ‘voluntary’ does not properly apply to such situations.”

Runaway and homeless youth are more likely to engage in substance use and delinquent behavior, become teenage parents, drop out of school, suffer from sexually transmitted diseases, meet the criteria for mental illness, and have an increased risk of being sexual exploited and trafficked, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP) and the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children (NCMEC) said in a statement in November 2019, while observing National Runaway Prevention Month.

The risk for homelessness is also increased for youth living in the foster care system, per that statement by OJJDP and NCMEC. In fact, youth who experience multiple placements in foster care, who have a history of running away from them, and who have spent time in a group home are most at risk of homelessness. Those aged 15 when they first enter foster care have the highest risk of running away. There are also gaps in the overburdened child welfare system that can lead to children being abused.

As we mentioned earlier, when it comes to the foster care system, too, while children are removed from their biological families for reasons that could include abuse, neglect, or abandonment, they may be subjected to these same traumas at the hands of anyone from caseworkers to even their foster and/or adoptive families.

In 2017, Biometrica published a piece by the Polly Klaas Foundation listing out one such example of foster care. Sandra,* a 16-year-old girl, was raised by her grandmother until the age of eight. She was placed in the foster care system upon her grandmother’s passing. At the age of 13, Sandra began running away from her placement home due to unwanted sexual attention from a caregiver in the home.

During her time away, a man named Darryl* befriended Sandra. She confided in Darryl about her grandmother’s passing and the discomfort she felt in her foster home. He sympathized with her and promised he would protect her. He offered Sandra the opportunity to live with him. Sandra met with Darryl several times before running away from home for good. Darryl told Sandra that she had to repay him for living expenses by exchanging sex with his friends and neighbors in the building for money.

Homeless youth also have a high rate of involvement in the juvenile justice system. According to OJJDP data per that 2019 statement, on any given day, over 43,000 young people — many suffering from substance abuse and mental illness, or both — are in juvenile corrections and treatment programs. One of the aims of the Office of Justice Programs is to help homeless kids who enter the juvenile justice system make their way out of it, with the goal of living safer and more fulfilling lives.

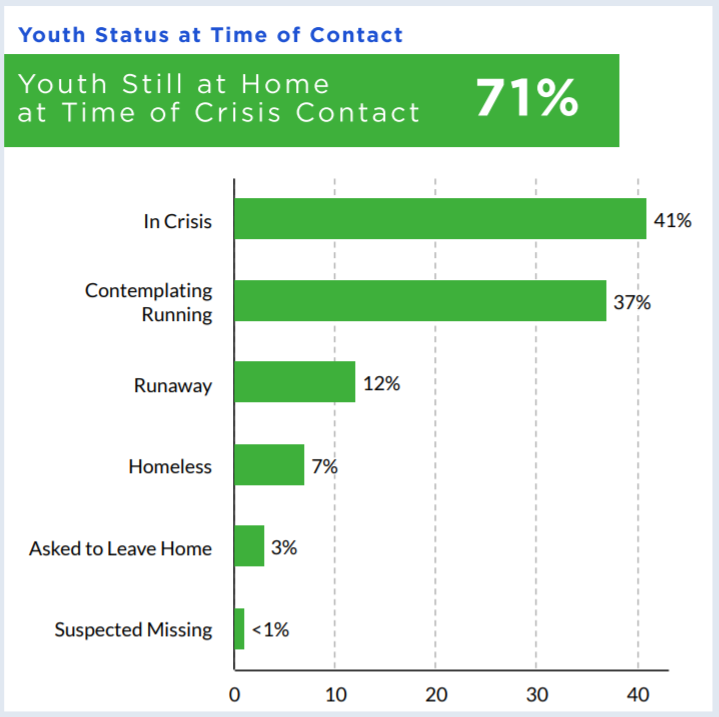

In 2020, 27,546 individuals reached out to the National Runaway Safeline (NRS) through the 1-800-RUNAWAY hotline and the various digital services offered through 1800RUNAWAY.org (live chat, email, and forum). A majority of those who reached out to the NRS were youth seeking for help for themselves (81%). But concerned individuals also reached out on behalf of youth, such as parents (6%), friends (5%), and adults (4%), among others including relatives, agency representatives, and police or probation officers.

Although a majority of the youth (88%) who reached out to the NRS for crisis intervention did so because of family dynamics, other common problems were emotional abuse (31%), peer/social issues (27%) — including problems with friends, internet relationships, gang or cult involvement, sexual activity, relationship problems, and independence — and mental health problems (17%). These categories were not mutually exclusive and those contacting NRS could report multiple problems.

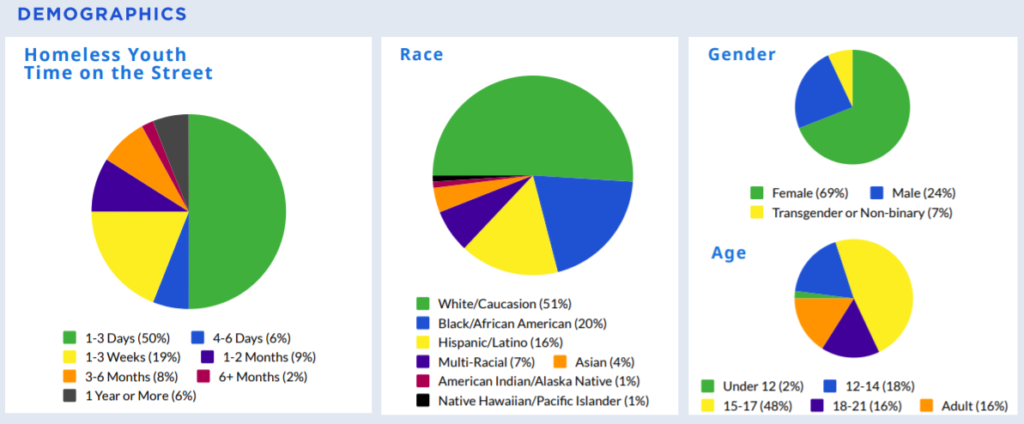

A majority of the youth who called the NRS were only able to survive homelessness because of friends and family networks, followed by personal funds, and through shelters and soup kitchens. But it’s important to note that 1% survived due to survival sex, another 1% by relying on the sex work industry, 1% by stealing, and under 1% on selling drugs.

*Sandra and Darryl are pseudonyms. Sandra’s story is like that of many at-risk youth, lured away from home by acquaintances and/or strangers who gain their trust.